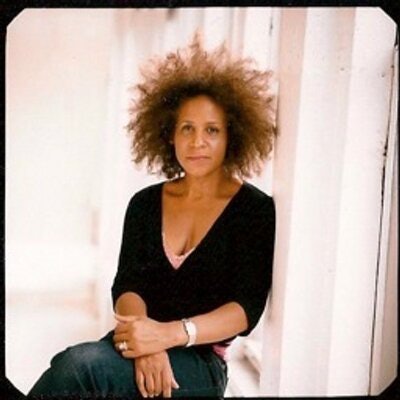

She has beaten a gilded path to a toney, racially diverse New Jersey exurb. On her most taxing days, her biggest responsibilities used to be walking the family dog, administering his cataract eye drops, waiting for repairmen and picking up her young son from school.

From the outside looking in, the Howard University alumna was living a near-perfect life with two “cute, bright” kids and a “cute, bright,” supportive husband.

It was a wonderful veneer, but behind the beautiful smile, she was slowly descending into a deep, dark hole of depression.

“Initially I wasn’t even aware it was happening,” says Little. “I was drinking and shopping, doing those distractions. I would look around and see women enjoying it, but I wasn’t.”

Little’s latest book, a memoir, Welcome to My Breakdown, published in April by Atria books, chronicles her battle with severe depression. It was not her first brush with it, but this bout was pernicious, lasting close to a decade, and was exacerbated by the failing health and ultimate passing of her mother.

“My mother was really incredible. I miss her as a person not just as my mom,” says Little. “She was someone who loved me. I wouldn’t have hit that low because I would have had my mother to talk to.”

For some in her circle, mainly Black women, it was difficult to understand what Little was dealing with. In one chapter, she describes how her hair colorist blithely suggested that she just “relax and go on and live Miss Ann’s life.”

That sort of existence is freighted with a complicated history. ‘“Miss Ann’ wasn’t a positive term for Black People,” writes Little. “Miss Ann was the lady of the plantation, weak, mean, and prone to fainting spells. These proverbial Southern White Women relied on their Black maids to do everything from breast-feeding and raising the children, to cleaning the house, cooking, and submitting to rape from her husband if said husband/master requested.”

In recent years, there has been more animated conversation about how to address depression and mental illnesses that disproportionally affect African-Americans. The economic collapse in 2008 did not help, as Black people, particularly first-time homeowners, overwhelmingly suffered adverse effects.

While depression doesn’t respect class or education, as Little can attest, at least she has the support and resources to combat it. Many African-Americans don’t. As the filmmaker Kevin Jerome Everson once said, in all seriousness: “Black folks don’t go to therapy; they go to church!”

Nana Carmen Ashurst, minister at Greater Centennial AME Zion Church in Mt. Vernon, N.Y., takes issue with that.

“That’s not the whole story,” she says. “A lot of Black people think they can do it by yourself with the help of God. The getting through it—you can’t do it yourself or with prayer.”

Ashurst, 64, who is invested in God and scripture more than most, knows first-hand.

“I suffer with depression,” she related, in a recent sermon titled “Beyond Tired.” “I don’t mean I get sad every once in a while. I mean without treatments I suffer weeks at a time, unable to function normally. Instead of a burning bush, I have my bedroom. I stay in my bed for days that run into weeks, with the lights low, unable to have a conversation, not able to even eat too much, completely without hope.”

Like other afflictions, depression carries a stigma. “Medication equals weakness in the Black community,” says Ashurst. “We realize we are trying to get to a better place. People who do that are admitting vulnerability. Depression is another health issue, and we have real reasons to be depressed. A lot of it isn’t situational. It’s illness. When you realize that you are not getting what you work for, that is debilitating. Your kids absorb how you behave, and it becomes generational.”

Little credits prolonged, intense therapy and her writing as helping her to stave off reoccurrences of her depression. And she is doing her best to help others break the cycle.

“I want to give people permission to talk about their mental wealth,” she says. “We just have some extra (stuff). Own it, own all of who we are, we are complicated, and we are in pain. I hope this opens up conversations. It’s not about money. Having it doesn’t insulate you. We wear masks.”

Nick Charles is a journalist based in Rockland County, N.Y.