With his camcorder in tow, Dr. Darnell Hunt began exploring Los Angeles soon after mass unrest began on April 29, 1992.

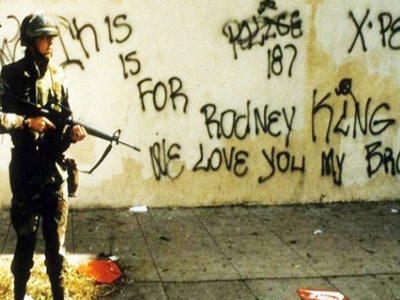

The uprisings by frustrated Angelenos followed the acquittals earlier that day in the trial of four L.A. police officers on charges of use of excessive force in the arrest and beating of unarmed, Black motorist Rodney King during a traffic stop that was caught on amateur video.

“Plenty of people were trying to tell stories to reporters who ended up telling a different story on the air and in newspapers,” Hunt recalls. “Certain media frames controlled the narrative in 1992. Reporters fixated on the crime frame and the breaking news format. They ignored what many people were saying during interviews because it didn’t easily fit into the crime frame and the preferred narrative.”

The disconnect between news reports and what minority residents were trying to convey at that time caused Hunt to dig deeper during subsequent months and years to determine what the unrest meant to different racial groups. It is also why he has, over the years, participated in symposia that examine the landmark events of 1992 alongside contemporary analyses.

“It’s easy to revise and reframe history that ends up obfuscating linkages between the present and the past,” he says. “The more things change, the more they stay the same. We shouldn’t reduce the events of 1992 to just what happened to Rodney King, or we miss the bigger lessons. With every milestone involving 1992, it’s another chance to take a bite at the apple, so I always look forward to participating in these discussions.”

Three university-sponsored symposiums in Southern California this week feature many scholars such as Hunt, who is now a UCLA sociology professor and director of UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies. The three conferences coincide with the 25th anniversary of the 1992 uprisings in L.A.

Tuesday, the University of California, Riverside (UCR) hosted a panel discussion titled, “The Afterlife of April 29, 1992 & the Fight for Racial Justice in South Los Angeles.”

Carol Park was barely a teenager in 1992.

Vandals looted the family-owned gas station operated by Park’s single parent, Korean American mother in the working-class community of Compton, south of L.A. Since age 10, Park had climbed onto a milk crate in order to see above the cash register to ring up gas sales on weekends. From behind bulletproof glass, the girl spelled her two older brothers. Because the business was open 24 hours daily, year-round, every family member pitched in.

“We still have a long road ahead of us in race relations,” says Park, a researcher at UCR’s Young Oak Kim Center for Korean American Studies, which sponsored the panel discussion. “Every anniversary of 1992 is like an ‘a-ha’ moment because there are still so many remaining issues to address.”

During her childhood, Park didn’t know that poverty and long-running oppression and discrimination by Whites against people of color had bred hostilities among the latter, sometimes resulting in tensions between minority communities. What she did know, and quickly became desensitized to, was that violence and gunfire were constants outside her family’s gas station. Shoplifting and racial slurs uttered by customers were also common.

As Park came of age, however, she began grasping that the events of 1992 symbolized much broader societal ills than a series of alarming statistics: 50-plus fatalities, thousands of people injured or arrested or both, and $1 billion-plus in property damage — businesses owned by Korean and other Asian Americans made up a disproportionately high share of it. These and other statistics have often been cited in news reports when describing the uprisings that stretched almost a week throughout much of L.A.

“Police brutality was, and still is, a problem,” Park says. “So are race-based, socioeconomic disparities.”

Hunt agrees, citing as recent examples the well-publicized problems and civil unrest in Baltimore and in Ferguson, Missouri. “When I saw TV reports from Baltimore and Ferguson,” he says, “I was taken back to 1992 all over again.”

However, because so much of the mainstream news media focuses on crime and street violence, the underlying causes of the unrest are still rarely and unevenly reported, he says.

In the late 1980s, Hunt, who held a bachelor’s degree in journalism and an MBA, was working at a TV news station in Washington, D.C., when he began noticing that its overwhelmingly White management team would discuss local neighborhoods of Black professionals as if they were crime-riddled eyesores. After realizing how much the management’s racial bias influenced the overall TV news narrative, Hunt changed his career plans and enrolled at UCLA for doctoral studies, examining how race, ethnicity and identity shape the construction of TV news and the viewers’ understanding of it.

Since earning a doctorate in 1994, Hunt has been a frequent commentator on race and the media. He says the media’s frequent use of words like “riots” when describing the 1992 uprisings “unfairly imply a lack of planning by organized protesters that can undermine political activity.”

Hunt points out that truces in L.A. gang wars in spring 1992, along with the posting of signs outside of stores reading “Black owned” during the uprisings were evidence of attempts to prevent minorities from turning on each other, although not every effort was successful.

These and other observations are why Hunt is participating in two of this week’s Southern California symposiums.

The University of Southern California is convening one, “Forward LA: Race, Arts and Inclusive Place-Making After the 1992 Civil Unrest.” Meanwhile, UCLA is hosting a series of panel discussions titled, “Sa-I-Gu: The Los Angeles Uprisings 25 Years Later — Witnessing the Past, Envisioning our Future.”

The Korean phrase “sa-i-gu” translates to the numbers four, two and nine, marking the historic date for Korean Americans similarly to how the phrase “September 11” denotes the terrorist attacks of 2001 in this country.

Like Hunt, Park will be a panelist at the UCLA symposium. She worked part time at her family’s gas station until she was in her mid-20s, having commuted back to Compton every weekend while attending college out of town. Her family sold the business less than three years ago.

Park is disappointed whenever she encounters young people across all racial groups who have never heard of the 1992 uprisings, but applauds those who are familiar with the events from 25 years ago “because they’re taking the time to investigate what happened, using social media and other tools of their generation.”

She adds, “It’s great they’re doing something.”

Hunt, meanwhile, offers a more nuanced view about today’s technology. During the civil rights movement, for instance, activists had to literally hit the pavement and distribute fliers and leaflets door-to-door to publicize rallies, marches and demonstrations in order to draw participation. The copies often were produced by a mimeograph machine — a device that most millennials have probably never heard of.

However, Hunt says, the tools of today’s digital age don’t necessarily facilitate for people the same level of emotional investment and tactile experience when it comes to participating in collective behavior, such as an organized protest or a grassroots movement such as Black Lives Matter.

“Thanks to social media, smartphones and other devices, the news media don’t have the same monopoly anymore,” Hunt says. “There are now so many more ways to distribute news, information and stories.

“But the thing is,” he continues, “it’s so fast and easy to post a photo, or to choose ‘like’ for someone else’s posting. You might think you’re doing something as an activist, but are you really doing something substantive to support a movement?”

These are the types of questions Hunt, Park and others aim to examine this week.

More information about the three scholarly conferences and other public events in Southern California connected to the 25th anniversary of the 1992 uprisings is available at: https://equity.ucla.edu/25-years-after-the-fires.

![Mentor Mentee [60287]](https://img.diverseeducation.com/files/base/diverse/all/image/2024/04/Mentor_mentee__60287_.662959db8fddb.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)