By all accounts, Dr. Leslie Wong has had a distinguished career in higher education.

After serving as dean of Evergreen State College and provost and interim president at the University of Southern Colorado, Wong was appointed president of Northern Michigan University, a position he held for eight years. In August 2012, Wong became the 13th president of San Francisco State University, which serves more than 30,000 students.

But Wong’s résumé is also unusual in one respect: he’s an Asian American college president.

While African-Americans make up about 6.2 percent of the nation’s college presidents and Hispanics about 5.9 percent, Asian Americans account for only 1.5 percent. The numbers are equally dismal among other executive positions in the academy, including deans, provosts and vice presidents.

Certainly, there’s been some progress in recent years, with appointments of Asian Americans to top positions at high profile schools, including Seton Hall; the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; the University of Maryland, College Park; the University of Houston; and San Francisco State. But the growth is only a trickle.

Several higher education administrators, scholars and college presidents attribute the low numbers to a variety of factors, including the so-called bamboo ceiling, subtle bias and a perception by some White administrators that people of Asian descent are content with working hard and getting results, and either have no interest in leadership opportunities or simply won’t be good at it.

Sam Museus, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Denver, says that Asian Americans are, in some respects, victims of their own success in the classroom and in the workplace.

“The assumption is that all Asian Americans are universally successful, which leads to their being invisible,” says Museus.

“The issue is not even on the radar of a lot of people. Even when diversity initiatives are pursued, Asian Americans are not seen as groups that need attention. The model minority assumption is that they don’t face race-related problems.”

Image issue

Asian Americans also suffer from another type of image problem, says Museus.

“While the model minority assumption is that [Asian Americans] are math and science nerds, the assumption is that [they are] not good enough leaders, that the men are not masculine enough [and] that the women are too feminine, submissive or subservient.”

According to Frank Wu, chancellor and dean of the University of California Hastings College of the Law, the numbers are “astonishingly low,” considering that Asian Americans are overrepresented in the academy as students, graduate students and faculty members.

“The problems start at the dean level,” says Wu, author of the book Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White and former dean of the Wayne State University Law School in Detroit.

“There isn’t a pipeline that’s being prepared. … There are those who claim that Asian Americans are not interested in leadership roles and that is simply not true.”

Wu believes there is more to the problem. He says people of Asian descent face resentment in U.S. society because of their perceived success, a factor that also leads many to have a lack of sensitivity to racial bias against them.

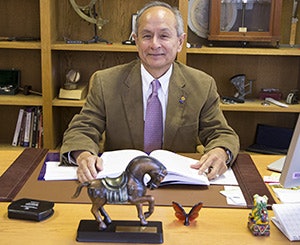

San Francisco State University President Leslie Wong is a rarity in the academy ― an Asian American in an executive position.

San Francisco State University President Leslie Wong is a rarity in the academy ― an Asian American in an executive position.

That perpetual foreigner syndrome may also explain some of the verbal racist attacks against University of Illinois chancellor Phyllis Wise last January when she opted not to close the campus despite the poor weather. On Twitter, the tweets were directed at her status as a woman of Asian descent. Some were written in the stereotypical voice of an Asian who speaks broken English.

Obstacles and advice

But there are other barriers beyond subtle and overt racism.

Wong says many Asian Americans are put off by senior administrative duties such as fundraising and athletic management.

“The whole area of fundraising [is scary to] many Asian/Pacific Americans,” he says. “I think for my group, Chinese Americans, that is chilling. Raising money chills our community. The whole notion of athletic management is chilling to them [as well].

“Most of our mentees say being in the public eye scares them,” adds Wong. “They say being in the spotlight, in the public eye, and having to make highly visible decisions, especially if you have to build community relationships, is intimidating. They tell me that the last time they had that kind of fear was in speech class when they had to get up and talk.”

Several Asian American college presidents offer a few strategies for breaking through the bamboo ceiling.

Among the tips are the following:

Find a mentor. “One of the things that has handicapped my community is that we’ve never really been formal about having a mentoring system,” says Wong. “When you talk to Hispanics or African-Americans, they can tell you in seconds who they call their mentors. I’ve been shocked how many Asian/Pacific Islanders can’t name one.”

Dr. Gabriel Esteban, president of Seton Hall since 2011, says he was “fortunate” to have found a mentor early in his career.

“I had two mentors. One was a chief academic officer [who] talked to me about a broad group of issues related to higher ed. [I] continued to benefit from their wisdom as [I] moved up.”

Groups such as Asian Pacific Americans in Higher Education and Leadership Education for Asian Pacifics, Inc. focus on the advancement of qualified Asian American faculty and administrators in the academy. In addition to annual conferences, they create avenues for mentorship.

Toot your own horn. Dr. Bobby Fong, president of Ursinus College, says, in the academic environment, it is important to be able to “rightfully claim credit.”

“One of the difficulties for many Asian Americans is that they come out of a culture where people try not to take credit for things,” says Fong, a former president of Butler University. “You need to be able to say on résumés and in annual evaluations [that] this is what I’ve been able to contribute this year. For many Asian Americans, that’s doing something that’s quite different.”

Continues Fong, “Another piece of advice is to be able to understand what it means to converse in [the] politics of the department. There is a complicated social fabric that one has to be part of to earn respect of one’s peers. Leadership often comes to people who have a network within the organization. Those aspects [are] not always comfortable for some people, particularly when your culture insists you wait your turn.”

Look for opportunities to serve. “As an assistant professor, the provost asked me to draft a response to a number of challenges posed by the accreditation team,” recalls Esteban. “Every time an opportunity came my way and they were looking for volunteers, I volunteered.”

Network. Esteban says that, while it is important for faculty members to go to networking events specific to their discipline, those looking to climb the rungs of leadership have to think broadly in terms of networking and picking up different skills.

“Another thing that serves me is that I can do financials,” he says. “I can do spreadsheets. Being able to work with numbers is very important as a college president.”