OiYan Poon, assistant higher education professor at Loyola University Chicago School of Education, said first-year grades in college are not a meaningful enough measure of a student’s potential.

OiYan Poon, assistant higher education professor at Loyola University Chicago School of Education, said first-year grades in college are not a meaningful enough measure of a student’s potential.NASHVILLE, Tenn. — Test scores and grades don’t tell universities enough about a prospective student, and there’s a need for race-conscious outreach and recruitment to bring more diverse students onto campus.

So argued two leading researchers of Asian American issues in higher education Monday at the national seminar of the Education Writers Association.

“The idea that grades and test scores are objective is debatable,” said Robert Teranishi, education professor at UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center.

He cited recent changes to the College Board’s SAT as evidence that the college entrance exam lacks validity.

“If it were perfect in defining merit, why would they change it?” Teranishi said.

Although Asian Americans are statistically seen as high achievers, Teranishi reiterated longstanding concerns about how the heterogeneity of Asian Americans often gets overlooked to the detriment of Asian American students who hail from groups—such as Southeast Asians—that struggle academically.

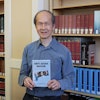

Teranishi was joined in his stance by OiYan Poon, assistant higher education professor at Loyola University Chicago School of Education, who argued that universities often employ criteria in admissions that favor White students—such as geography and residence—and fail to capture important information about minority students by simply looking at grades and test scores.

“SAT test scores tell us about 5 percent of variance in first-year college grades,” Poon said. “Even the College Board is questioning what do these test scores tell us.”

While high school grades are much better at predicting first-year grades in college, Poon said, first-year grades in college are not a meaningful enough measure of a student’s potential.

Haibo Huang, a Harvard-educated physicist who serves as a California-based board director for the 80-20 National Asian American PAC, said he agreed with the need for affirmative action based on socioeconomic status but drew the line at using race.

Huang spent much of his time explaining his position against SCA5, the technical name for the recently defeated Senate Constitutional Amendment in California that would have let voters decide whether to reinstate race-conscious affirmative action in higher education.

While proponents said the measure was necessary to achieve diversity on campuses in California, Huang dismissed SCA5 as a “fraud distraction.”

“The real issue in this whole debate is the pipeline issue of high school students that are graduating,” Huang said, lamenting that international student assessment scores consistently show the U.S. lagging behind other developed nations. “And this must be fixed earlier than college admission.”

Conservative writer Ron Unz noted that, how when SCA5 was first introduced, it was assumed that it would garner Asian American support.

But once “ordinary Asian Americans” began to learn about the proposed measure, he said, they opposed it because of concern that they were being discriminated against in elite institutions.

Teranishi countered that “there is no ‘ordinary Asian’” and listed the dozens of ethnicities, hundreds of languages and various immigration histories and experiences that fall within the group known as AAPIs, or Asian American and Pacific Islanders.

Unz said there’s plenty of evidence to suggest Asian Americans are being denied access in the Ivy League schools.

“I didn’t find a smoking gun,” Unz said of his efforts to document discrimination against Asian Americans at America’s top universities. “I found a smoking Howitzer.”

Unz presented statistics that show that, while the number or percentage of Asian Americans has increased in recent years, the same is not true of Asian American enrollment at the Ivy League schools.

“You have to really ask yourself: Isn’t it odd that the number or percentage of Asian students has doubled, while enrollment (of Asians) has declined at some of the Ivy League schools?” Unz said.

He accused the Ivy League schools of keeping the data on the ethnicity of their applicant pools shrouded in secrecy and challenged reporters to pry the data loose.