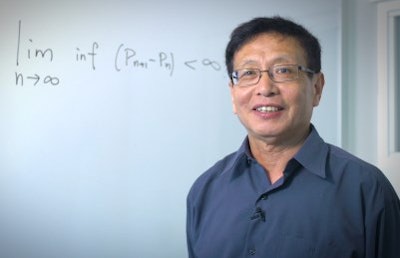

In 2013, Dr. Yitang Zhang proved an element of analytic number theory that had eluded mathematicians for centuries. (Photo courtesy of the University of New Hampshire)

In 2013, Dr. Yitang Zhang proved an element of analytic number theory that had eluded mathematicians for centuries. (Photo courtesy of the University of New Hampshire)Every now and then, a light shines on a beautiful mind. For Dr. Yitang Zhang, that moment came when an article of his was published in the Annals of Mathematics, validating several decades of quiet, dedicated work.

In the Annals article, published in 2013, Zhang proved an element of analytic number theory that had eluded mathematicians for centuries. He proved that the gap between two consecutive prime numbers is bounded by a fixed number, infinitely often.

As a result, Zhang was awarded a MacArthur grant and elevated to full professor status in the Department of Mathematics at the University of New Hampshire (UNH), where previously he had worked as an adjunct.

Zhang first began to consider the bounded prime gap problem in 2010. “It was difficult,” he says, in his characteristically understated way, of his search for the proof. Zhang says he thought about the problem “most of the time,” spending eight to 10 hours a day working on it.

Mathematicians across the globe were astonished when they learned of his proof. Zhang, previously obscure, became renowned. Despite the newfound acclaim, Zhang maintains a calm, almost equivocal demeanor. He is understated, even when speaking about a problem that consumed his thoughts and free time for two years.

“I was interested in such a problem, so much,” he says. “I realized it was an important problem.”

His self-effacing attitude helped Zhang stay focused on his goal for two years, working in solitude. Zhang says that anyone who wants to solve the seemingly unsolvable must possess unflagging determination.

“If you really love mathematics, or if you really love the sciences, don’t easily give up,” he advises.

That maxim appears to have guided him through his childhood and youth, growing up in Communist China. Born in 1955 in Shanghai, Zhang loved books and mathematics as a child.

“When I was very young, I really loved math, but I don’t know why,” he says. However, when he was 15, the regime sent him to move to a farm in the countryside, where he was forbidden to read books.

Eventually, Zhang moved to Beijing, where he decided to study at Peking University. He taught himself all the high school courses he had missed in a matter of months and entered the university at age 23. After graduating with a master’s in mathematics in 1984, Zhang set his sights on earning a Ph.D. in the United States.

“That time, we tried to learn something more in math,” he says of his decision to move to a foreign land.

A year later, he was at Purdue University in Indiana on a full scholarship. There, Zhang chose to grapple with the Jacobian conjecture—a problem first posed in 1939 that has, to date, not been proved—for his thesis.

Although Zhang showed unusual talent and courage in his intellectual pursuits, he was unable to move into a professorial or even adjunct role until 1999, eight years after he received his Ph.D. Why this is the case remains a bit murky.

His academic adviser, Dr. Tzuong-Tsieng Moh, evidently did not write him a recommendation, although there are varying accounts as to whether Zhang ever asked Moh to write him one.

“To the date Yitang announced his monumental result, I did not know what was the best for him, though I was sure of one thing—he could not survive the life of ‘tenuretrack,’ ‘tenure’ and ‘promotions.’ It was not his type. I regarded him as a free spirit, and I should let him fly,” Moh wrote in an article on Zhang’s time at Purdue, by way of explanation for the lack of recommendation.

Without a letter of recommendation, a referral, published papers, and only his thesis on an unproved conjecture in his favor, Zhang took on odd jobs to make a living.

He worked as an accountant, delivery worker and at Subway. Eventually, through a friend of a friend, he was able to get a job as a lecturer at UNH in 1999.

Asked whether he found those years difficult, Zhang simply says, “That’s correct.”

Now that he has a full professorship, life is easier. “As a full professor, it’s more money and reduced teaching,” he says, laughing.

Still, Zhang’s life has not become any more lavish or extravagant. He sold his car several years ago and lives close to work in Durham, a small New England town full of stately brick college buildings and traditional clapboard colonial houses, home to the university.

Zhang spends his time at work, and now that spring has arrived, he is able to walk and think for hours at a time outdoors.

He has not yet revealed what problem he will tackle next.

“I’m not sure,” Zhang says. “Just I’m still considering some other problems, also in number theory.”