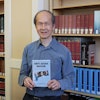

W Dr. Robert Teranishi

Dr. Robert Teranishi

For instance, in April 2024, the initiative hosted the first-ever Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Higher Education Leadership Development Summit. The summit – which drew faculty, staff and students from around the world – took place at the University of California, Berkeley. A year prior, Berkeley had been awarded its first federal grant as an AANAPISI – or Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institutions.

Under Trump 2.0, the White House Initiative on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders – also known as WHIAANHPI – is no more. It became one of the many casualties of the Trump administration’s crusade against diversity, equity and inclusion programs, or DEI.

Scholars say the dissolution of WHIAANHIP is more than symbolic – that it will lead to diminished resources and attention for various issues and challenges that confront students from the demographic the initiative was meant to serve.

“It is significant anytime there is an executive order that is specifically inclusive of the AANHPI population simply because it does not happen very often,” says Dr. Robert Teranishi, the Helen Chu Endowed Chair in Asian American Studies, and a professor of social science and comparative education at UCLA.

“I’m old enough to remember when it started,” says Dr. Julie J. Park, professor of education at the University of Maryland, College Park, in reference to when President Bill Clinton first established the initiative in 1999.

“I think the decision to dissolve it – unfortunately in this administration it’s not totally surprising since they’ve cut so many other things – but it’s really disappointing,” Park says. “I think we’ll have widespread consequences for the Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities.” Park listed issues such as poverty, census counting and mental health in the aforementioned communities that she says will now get less attention since the White House initiative disbanded.

“Anytime you put the White House

name on it, it amplifies it to another

level, so that was helpful in legitimizing the concerns that people have been talking about for years and years that don’t get a lot of attention,” Park says.

Dr. Pawan H. Dhingra, a professor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Studies at Amherst College, and immediate past president of the Association for Asian American Studies, raises similar concerns.

“I believe they were helpful in thinking about some of the lesser known issues that affect Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders,” Dhingra says, also listing mental health and poverty, as well as bullying in schools as examples. “What I always appreciated about [the initiative] is that they were trying to move the needle on these issues that most others aren’t going to be thinking about,” Dhingra says.

But did WHIAANHPI actually move

the needle on the issues it says were

important? Dr. Julie J. Park

Dr. Julie J. Park

Diverse reached out to several members of the 25-member WHIAANHPI but was unable to secure a comment. There could be a reason for the silence. One former member of the initiative told Diverse that commissioners “have been warned to be careful of retaliation by MAGA.” Thus, declining to comment could be a protective measure meant to stay out of the crosshairs of the Trump administration, which has not hesitated to settle old scores, such as going after FBI agents who investigated President Trump for his alleged role in the Jan. 6 insurrection in a case that has since been dropped.

In early March, the Trump administration took aim at the U.S. Department of Education itself, decimating the department – including IES, its research arm – in one of a series of salvos that come amid plans to shut the department down for good. If the Education Department is ultimately shuttered, it will undoubtedly raise a series of questions, issues and problems for the nearly 200 institutions of higher education that are designated as an AANAPISI – or Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-Serving Institution. Beyond Berkeley, examples of AANAPISIs include a wide range of institutions, such as Montgomery College, the University of Minnesota and California State University.

“Most are concentrated in areas with high percentages of AAPIs, including California, Hawaii, Illinois, New York, Massachusetts, Maryland, Texas, Washington, and Guam,” states the Postsecondary National Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based organization whose purpose is to boost the knowledge, capacity and diversity of federal higher education policymakers, leaders and thinkers.

To achieve AANAPISI status, among other things, an institution’s undergraduate student enrollment must be at least 10% Asian American or Native American Pacific Islander. And at least half of enrolled students must receive federal financial aid.

Institutions that meet these standards can apply to the U.S. Department of Education for AANAPISI status, which enables the school to apply for discretionary grants of up to $350,000 per year for five years, or a total of $1.75 million. Funds can be used for a variety of purposes, such as curriculum development, faculty exchange or even classroom renovation.

“Rising Together: The Promise of Equity, Justice, and Opportunity for Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Communities,” is one of the last products of the WHIAANHPI. Released in January 2025, the report explains the role that the Education Department was supposed to play in the future of AANAPISIs.

For instance, the report called for the U.S. Department of Education to increase increase data disaggregation efforts, as well as resources for Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander Serving Institutions through various mechanisms.

The disaggregation of data concerns taking a more granular look at students from the demographic in question, rather than leaving intact what scholars say are harmful stereotypes about Asian Americans as a “model minority.” The stereotype, they say, tends to obscure the disparities that exist within Asian American and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities.

“For instance, higher education serves as one important example,” the “Rising Together” report states. It notes statistics that show the college attainment rate for AA and NHPI students is approximately 51%. “Yet, breaking this data down by ethnic bachelor degree attainment reveals a startling difference: Taiwanese report the highest rate of attainment at 74.5%, while only 15% of Laotians, 14% of Samoans, and 5.2% of other Micronesians reported the same.”

The report also laments what it describes as funding disparities that AANAPISIs face among other Minority Serving Institutions, or MSIs.

For example, in FY2022, the report notes, each eligible AANAPISI institution, if funded, would receive $78,648. Meanwhile, HBCUs would receive $4,614,354 and HSIs would receive $561,087.26, the report notes.

“There are many reasons for this disparity related to historical factors and enrollment patterns, but the assistance given to AANAPISIs is clearly the WHIAANHPI than to keep it alive only to half-heartedly go through the motions?

Dhingra says there’s value in keeping the initiative alive, even if its power is diluted due to lack of sincere support.

“Going through the motions does have impact. There is something there,” Dhingra says. “But now what you’re basically saying is we don’t want to pay attention to this group anymore. And there is a concern that this is the same group that has always been overlooked and thought not to have problems. So, if no one is drawing attention to them, no one is going to pay attention.”

Park, the education professor at Maryland, agrees, adding that the initiative created a way for members of the Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities to liaison with the White House.

“In terms of what it symbolized, ‘We care about your voices. We care about your communities,’ it was a way to be able to create those relationships and pathways to communication,” Park says.