From Rosewood in Florida to Greenwood in Oklahoma, American history is replete with stories of communities of free and enslaved Black people being terrorized and killed in violent attacks – or rebelling against oppression under the leadership of the likes of Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner.

A much more obscure but no less horrific historical event is the subject of a new book by University of Houston history professor and historian Dr. Matthew J. Clavin.

Dr. Matthew J. Clavin

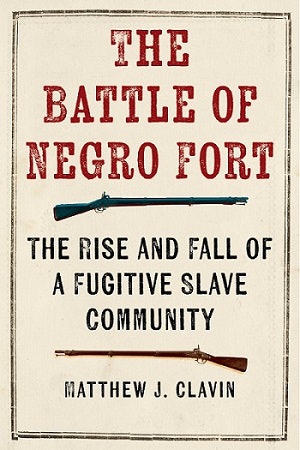

Dr. Matthew J. ClavinIn The Battle of Negro Fort: The Rise and Fall of a Fugitive Slave Community – published by New York University Press and scheduled for September release – Clavin relates the dramatic events of an illegal U.S. army-navy mission into Spanish Florida after the War of 1812. They attacked Negro Fort, a free and independent community of runaway slaves living outside the U.S. border in a wilderness fortress abandoned by the British and turned over to them after the war ended in 1815.

Situated atop a steep bluff overlooking the Apalachicola River, the fort was a haven for runaway slaves, who for generations had been fleeing slavery in the United States. Some had fought on the British side in the war. The fortress population was heavily armed for self-defense and steadily growing, numbering upwards of 1,000 at the time of the battle.

The battle began July 15, 1816 and ended 12 days later, resulting in the capture or death of nearly every fugitive slave while intensifying the subjugation of southern Native Americans who fought alongside them. Led by then-major general and later president Andrew Jackson under the false pretense that the fort’s inhabitants posed a violent threat to the United States, the U.S. forces were among hundreds of American soldiers, Black fugitive slaves and Indian warriors – who fought on both sides – engaged in the fight.

Negro Fort was the largest and most secure sanctuary for fugitive slaves that has ever existed within current United States boundaries. And the 1816 battle over it was the only time in U.S. history when the government destroyed a fugitive slave community on foreign soil.

Clavin, who has authored other books – including one about Toussaint Louverture and the Civil War – chatted with Diverse about his latest project.

You became aware of the story of Negro Fort as a graduate student. What motivated you to want to tell the story now?

One of the hardest things about writing history is having access to the primary sources. To do the history of Negro Fort justice, I needed to examine British, American, and Spanish sources. As you can imagine, it was difficult to find the time and resources to perform research in such disparate places as New Orleans, Washington, D.C. and London. Once I accomplished that, I was finally able to write Negro Fort’s truly incredible history.

I went into this project thinking the accounts of Negro Fort written by American citizens and officials, who claimed that Negro Fort’s residents posed a threat to settlers living along the southern frontier, were at least somewhat reliable. I found, however, that these reports were greatly — if not completely — exaggerated or fabricated. The fugitive slaves who inhabited Negro Fort were not seeking vengeance on their former owners. Nor were they out to topple the institution of slavery. Much to the contrary, they simply wanted to be left alone. The only thing they were after was freedom. The Americans who presented Negro Fort as a grave threat to the peace and security of the southern border did so in order to justify the fort’s destruction.

What does the story reveal about relations between Native Americans and African-Americans, particularly slaves, in early U.S. history?

Readers expecting to find a heartwarming story of Black and Indian resistance to White oppression will be disappointed. As historians of the southern frontier have long demonstrated, Native Americans across the southeast often inhabited the grey area between White freedom and Black slavery. For many of them, the best way to secure their own future was to unite with their White neighbors and serve on the front lines of the United States’ undeclared war against fugitive slaves. That being said, Negro Fort would not have survived as long as it did without the assistance of the fort’s Creek, Choctaw and Seminole allies. Cross-racial resistance to American expansion was real.

As a historian and history professor, do you see that moment in U.S. history fitting in with the debate about forming a commission to study reparations for American descendants of slaves?

I do, especially since the Battle of Negro Fort offers such a clear and concrete example of the United States government’s active oppression of Black people. Still, Negro Fort reminds us just how complex this debate will have to be, as the fort’s story can only be told from a transnational, transatlantic and global perspective.

Is there anything in particular you want readers to think or feel when they have finished reading the book?

I certainly do not want readers to feel sick to their stomach when they discover how Andrew Jackson and the United States government spent several years and untold resources capturing and killing fugitive slaves, but I think they might. Rather, I hope readers will come away from this story — like I do — with an important reminder of just how courageous and undaunted enslaved people were in their quest to be free. Learning about these Black freedom fighters, who were continually assisted by their White and Indian allies, should be an uplifting experience, which just might provide some solace in such a difficult and divided time as this.

What are you currently reading?

Oh, boy! Great question. I just finished two books that I literally could not put down: Ioan Grillo’s El Narco and Steve Brusatte’s The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs. As you can see, I like to read widely, especially in the summer. But I still try to look at the newest early American history titles as often as possible. Thus, I have also just completed Joanne Freeman’s The Field of Blood, which details political violence in the antebellum era. It really is a must-read for those who are on the verge of giving up on the American political system. As Freeman shows, bitter conflict has, for better or worse, been at the center of our political culture since the beginning.

LaMont Jones can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on Twitter @DrLaMontJones