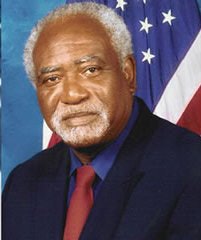

U.S Rep. Danny K. Davis says that each generation has to win freedom “and win it again.”

U.S Rep. Danny K. Davis says that each generation has to win freedom “and win it again.”Danny K. Davis remembers being driven to a one-room school house in a flatbed truck outfitted with nailed-down benches for the students to sit on. Sixty years ago, Brown v. Board of Education made the substandard early education that Davis, now a U.S. representative from Illinois, received, illegal.

Yet how much ground has been gained in those 60 years? “Many of the problems … that we were experiencing in 1954, we’re still experiencing now,” said Davis. “So freedom is a hard-won thing. Each generation has to win it, and win it again.”

The panel, “Educational Success for Black Men and Boys in a Post Brown v. Board of Education Era,” addressed issues of continuing inequality in the U.S. school system at the Rayburn House last Thursday.

Data collected by the U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Office show that courses essential for college preparation are quite simply unavailable in some U.S. high schools. Of the high schools surveyed, only 50 percent offer calculus and only 63 percent offer physics.

The panelists described an American educational landscape beset by a variety of numerous ills, which result in an “achievement gap,” a term that has come to blanket all sorts of issues. In simple terms, in 2009-2010, the high school graduation rate for Black male students was 52 percent, while, for White males, the graduation rate was 78 percent.

Dropping out of high school does not simply mean lower wages and diminished job prospects. It also correlates with the probability of incarceration. “We have to be cognizant of our responsibility not to reduce the achievement gap, but to eliminate the achievement gap to get our children out of what the Childrens Defense Fund calls the “cradle to prison pipeline,” said Rep. Bobby Scott of Virginia.

According to the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, 58 percent of youth admitted to state prisons are African-American.

House Democratic Whip Steny Hoyer said, “Our system of public education, which ought to be the best in the world, is leaving many young people, especially African-Americans and other minorities—boys in particular—behind.”

Hoyer recalled attending a majority White high school in Prince George’s County, Maryland. “Prince George’s County was not fully integrated until 1973,” he said. “The poverty line in many cities still traces the color line.”

Though schools have become more diverse since Brown v. Board of Education was handed down, White students are still less likely to attend diverse schools. According to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Education, only 15.9 percent of White students attend a “minority-majority” school.

Dr. Ivory Toldson cautioned the audience against “misconstruing the numbers” about the so-called school-to-prison pipeline, arguing that the negative media reinforces stereotypes of Black male youth as threatening or violent. Toldson, selected by Diverse as a 2013 Emerging Scholar, is a professor at Howard University and deputy director of the White House HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) Initiative.

The solution to these ills remains nebulous, according to the panelists. Scott cited the important work of programs such as Upward Bound and Gear Up in developing youth leadership.

Professor Roy Jones, executive director of the Call Me MISTER Program at Clemson University, called attention to the program, which incentivizes Black male students to become teachers. As of 2010, only 2 percent of teachers nationwide were African-American men. The program aims to provide more role models for Black students.

Catherine Morris can be reached at [email protected].