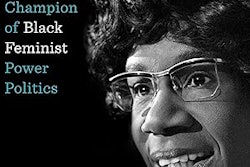

Diverse: Issues In Higher Education co-founders Dr. William E. Cox (left) and Frank L. Matthews.

Diverse: Issues In Higher Education co-founders Dr. William E. Cox (left) and Frank L. Matthews.

An advocate for education, Cox’s business acumen and creative mind would prove beneficial in the creation of one of the nation’s most successful minority-owned publications, Diverse: Issues In Higher Education.

Along with his business partner Frank L. Matthews, he set out to dramatically transform the higher education landscape with the founding of Black Issues In Higher Education, later renamed Diverse: Issues In Higher Education in 2005.

At a time when so many Black-owned publications have disappeared, Diverse continues to thrive, providing deep analysis, hard-hitting commentaries, and a contemporary view of the many issues that impact diversity, equity, access, and inclusion in higher education.

Cox died in March, at the age of 79, after a lengthy illness. His lingering impact on higher education will undoubtedly be felt for many decades to come, particularly as colleges and universities continue to grapple with how best to diversify their institutions amid systemic racism and disparate inequities that have festered across the years.

“Before the founding of Black Issues In Higher Education there was a deafening silence on issues related to Blacks and other minoritized groups in the academy,” says Dr. Charlie Nelms, chancellor emeritus of North Carolina Central University and one of the nation’s most prominent higher education leaders. “With the founding of Diverse by Bill Cox and Frank Matthews, all of that changed. In recent years, many other publications have increased their coverage of the people, policies, and programs impacting higher education, but none have done it as authentically, comprehensively, and consistently as Diverse. While Bill’s physical presence leaves a huge void, his voice and vision will always be with us.”

For Cox, the standard was always excellence. He believed that education could be the great equalizer in society and that access to education was something that should be afforded to all.

He was passionate about higher education, including Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), and would proudly serve as a trustee of his alma mater at Alabama A&M University until his health began to fail.

Early Beginnings

Born April 25, 1942, in Pensacola, Fla., Cox was raised in a small industrial Alabama town called Bay Minette, which sits about 190 miles from Birmingham and forty miles from the Florida state border.  General Colin Powell, left, and Dr. William E. Cox.

General Colin Powell, left, and Dr. William E. Cox.

Though his parents did not have a college education, Cox was inspired by a Black high school teacher and Alabama A&M University alum who encouraged him to enroll in college. Following in the footsteps of his brother, Cox — one of four children — went on to Alabama A&M University and majored in industrial arts.

It was at Alabama A&M that he would meet his future bride, Lee Foster. The two married in 1964.

“He was an upper-classman,” recalls Lee, who majored in biology and general sciences and finished her studies in three years, graduating a year after Bill earned his degree. She would eventually go on to pursue a long career in K-12 education, first in Alabama and later in Virginia.

Cox started his first job working at General Electric. He was hired as a draftsman and went on to work on logistics connected to the famous Apollo spacecraft. Headquartered in Huntsville, he stayed at GE for about two years before securing a job at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Ala., which houses, among other things, the offices of the Department of Defense, Department of Justice, and NASA.

“He was teaching in the space program,” Lee recalls. “He was piggybacking on what he was doing at General Electric and teaching technology.”

But by 1968, with the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Cox was ready to leave the U.S. to escape the racial turmoil that had triggered race riots in urban cities across the nation, most notably in Detroit, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles.

“It was a very emotional time for all of us at that point,” remembers Lee. “And Bill just kind of wanted to get the hell out of the country.”

He heard about an opportunity at the Arsenal to take a job overseas in Frankfurt, Germany. Pregnant with her first child, Lee was initially ambivalent about leaving the U.S. but believed that the opportunity could be transformative for herself and her young family.

“I thought, ‘he has lost his mind,’” says Lee with a chuckle. “We were from the South. We didn’t know anything about traveling overseas.”

But she relocated to join her husband, with William Jr. after he was born, where they would remain from 1968 until 1974. It was there that William and Tara — their two children who now have leadership roles with the company that Cox helped to create — spent their early childhoods.

Cox earned two master’s degrees in counseling psychology and public administration, before enrolling in an Ed.D. program in higher education administration. But it was his long civilian career in the U.S. military that brought him early accolades.

“Bill was responsible overseeing educational opportunities for the Air Force,” says Vernon Taylor, who met Cox in Germany and established a decades-long friendship. He considered Cox to be a dedicated mentor. An education officer for the U.S. Air Force, Taylor says he was struck by Cox’s strong work ethic.

“We didn’t have that many Black male leaders around, so I respected him for his expertise and straightforwardness,” says Taylor. “I’ll always remember his professionalism and his honesty. He was a very, very professional person.”

Though he was responsible for spearheading all the educational programs for the Air Force and had already established his bona fides there, Taylor remembers watching Cox get passed over for jobs that he was over-qualified for.

“At some point, he said, ‘enough is enough’,” says Taylor, who admired Cox for earning his doctorate and always advancing himself educationally. “So, it made sense to me at the time that he was going to quit to work full-time on the magazine. There were many people, including me, who didn’t think it was going to work, but he was determined and had the right approach and before you knew it, the same people who had overlooked him for opportunities were inviting him to deliver presentations.”

Taking a risk

As Lee Cox tells it, she was definitely nervous when Bill decided to venture full steam ahead on building a national publication and left the security of his full-time job behind. It was a risk.

“One day, he came home and told us he was quitting his job,” she recalls. “All I could do was, ‘Oh Lord, here we go again’,” she recalls with a chuckle. Their oldest son, Will, was slated to head off to college that fall.

“He’s always been so successful with whatever decisions he made, so all I could do was support him and I said, ‘well, at least my mom and dad are still living and working, and I can get my son educated.”

Lee connected her husband to Matthews, who was on the faculty at George Mason University and active in the Fairfax County NAACP.

“We were all civically inclined,” says Lee Cox, who was charged with helping to integrate the public schools in Guntersville, Ala., in 1964. Fairfax, Va., she remembers, was behind the times on school integration and had not started to integrate its schools until the mid-1960s.

After Frank and Bill met, “they got together and started scheming and coming up with ideas they wanted to do,” says Lee, adding that they ultimately settled on building a national publication.

While he was not a trained journalist, Cox knew the importance of storytelling and used his role as a champion to help showcase the talent of Black scholars, including those who found it difficult to find a public platform.

“We started Black Issues In Higher Education simply because there was a void in the higher education community. The only one out there in higher education at that time was The Chronicle of Higher Education,” Cox said in a 2019 interview. “We attempted to do something for Black faculty and administrators and so Black Issues was started. When we started in 1984, we were only coming out once a month. And I told Frank that in order to attract advertisers, we needed to be more frequent and so we started to come out twice monthly, after two years.”

It was that kind of business prowess that Matthews always admired about his business partner.  Dr. William E. Cox, left, and former U.S. President Barack Obama.

Dr. William E. Cox, left, and former U.S. President Barack Obama.

“We found that business and education can complement each other very well,” says Matthews. “Bill was unmitigated in his passion for the power of education.”

Building Black Issues Book Review

Even as Black Issues In Higher Education took off, Cox had the vision to expand the publication’s enterprise by founding Black Issues Book Review (BIBR), which helped to put Black authors on the radar by pushing these writers to self-publish their work.

Veteran editor Angela Dodson had the opportunity to work with Cox over many years, beginning with the launch of Black Issues Book Review in 1999. She was one of the original contributors. She became executive editor in 2003 and continued running the magazine for a while after Cox sold it in 2006.

Later, Cox hired her to fill various freelance roles, including writing and editing for Diverse: Issues In Higher Education and for Cox Matthews company projects over the last two decades.

“His creation of Black Issues Book Review at a time when a renaissance of African American publishing was in its infancy, was truly visionary and was a dominant force in its success,” says Dodson. “BIBR was the main vehicle and the only lasting platform to support writers, publishers, and other creators in that space. The magazine made many writers' careers. Issues became collectors' items. The magazine is still talked about and is sorely missed.”

Adrienne Ingrum was the founding associate publisher of BIBR. She says Cox noticed the uptick in book interest in his flagship magazine, and, referred by Cheryl Woodruff, reached out to her to create four special supplements annually.

“I suggested he create a separate publication. He ran numbers and said, ‘If you could make it bi-monthly — six issues per year — rather than quarterly, it could be profitable.’ The rest is history. It was the thrill of my career to help Bill start the magazine and publish alongside him.”

Ingrum calls Cox a “visionary who foresaw the cultural shift that Black books have created in the publishing industry and the entire world of entertainment and education,” she says. “Bill underwrote the progress we now experience by investing in Black Issues Book Review. That start-up was probably two decades too early to make bank on the current market for Black books, but we can all thank Bill because BIBR did much to usher in the success that BIPOC publishing imprints, Black and brown authors, and People of Color book industry professionals enjoy today."

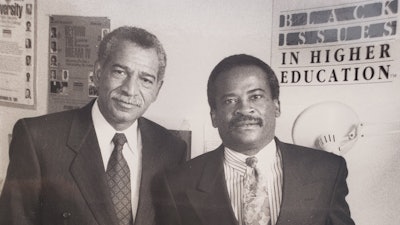

In February, Matthews stopped by the home of his longtime friend to check in on him. The two sat in the den “cackling, laughing, and having a good time,” reminiscing about the good old days. They thought about the dogged hours that they spent at their full-time jobs during the day and how they stole away in the evenings and weekends to work on Black Issues. Cox reminded him how in 1986 — two years after the publication made its debut — he would quit his job at the Pentagon to focus his efforts on building the company.

Cox affirmed that it was one of the best decisions he had made.

“I’m so glad that I stopped by to see him,” says Matthews. “We spent that afternoon counting our blessings. We tried to be outstanding, strive for excellence, and we always tried to get it right.”