As more states with conservative leaders pass laws to end or curtail diversity initiatives in higher education, a number of higher ed stakeholders say they are intensifying efforts to ensure access and success for the very students who are being targeted.

Cheryl Crazy Bull has been president and CEO of the Denver, Colorado-based American Indian College Fund since 2012, and she previously served as a president and a vice president of two tribal colleges, so she has seen the higher ed landscape for indigenous students change over the years.

Dr. Antonio R. Flores

Dr. Antonio R. Flores

Crazy Bull is referring to South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem’s 2021 executive order declaring that public colleges’ diversity centers and multicultural offices, which served ethnic minorities as well as other marginalized students including LGBTQ+ and veterans, would be replaced by “opportunity centers.” Noem had previously accused the diversity spaces of “advancing leftist agendas.” Despite opposition from student groups and after a number of faculty and staff resignations, the replacements have taken place.

South Dakota is just one example of Republican-led states taking action against diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in academia. As the country celebrates Pride Month, states are passing a flurry of laws against transgender and other LGBTQ individuals and diversity curricula.

Crazy Bull pointed out the importance of higher ed leaders having a clear sense of purpose in the face of these actions. For her, that purpose is deeply rooted in her understanding of the struggles of her community. “I often talk about the tribal college movement, tribal higher education supporting tribal self-determination and individual self-determination, so that our people can be prosperous.” However, she noted, Native student enrollment is declining across the country. “There are lots of barriers including financial ones, but the really big one is, can students even see themselves in the path to attending a higher ed institution.” She explains that, given the decline, support services are being scaled back in many states at a time when they are needed more than ever.

“I think it’s really important for all of higher education to be really in tune with this social and economic environment,” said Crazy Bull. “The United States was built on the blood of Native people and Black people and other people of color.”

In terms of day-to-day administration, Crazy Bull points to teamwork. “I think a best practice is to build your confidence in your team, and I learned over my years of experience that as a leader it’s important to be able to hear from your team what kind of communication practices, what kind of information-sharing works for them,” said Crazy Bull, also noting her belief in the use of lots of tools and different kinds of assessment strategies.

The American Indian College Fund is the nation’s largest charity supporting Native higher education and has distributed more than $259 million in scholarships and grants for programs and services since it was founded in 1989.

The value of teamwork

Dr. Antonio R. Flores, president and chief executive officer of the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU), agrees with Crazy Bull about the importance of what he calls “creating a culture of teamwork and collaboration.” Flores said, “I think when people embrace that [concept] and make it part of their lives, they really multiply their productivity because they are not feeling that they’re doing things by themselves in isolation but rather working with the entire team.”

Flores also said continuity of leadership is important, and there needs to be a sense of equal value among the team members. “To me the receptionist here at our headquarters in San Antonio is just as important as the president of this organization because she is the first one to welcome visitors and to really give the first impression about the organization to people who come to meet with us.”

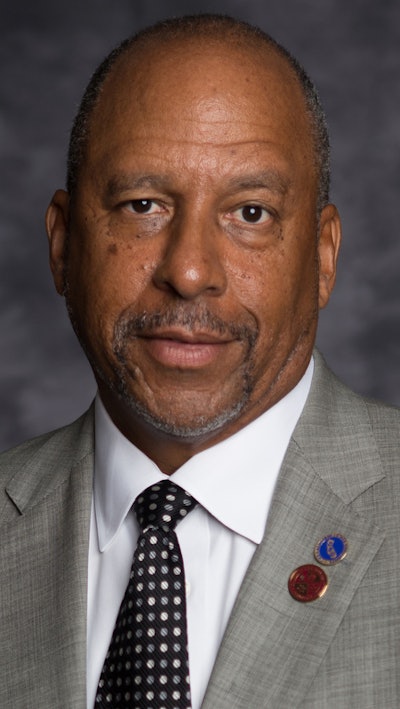

Dr. Thomas Parham

Dr. Thomas Parham

At the higher ed level, Flores said the disparities exist but in a different way. “The most endowed higher education institutions have all the whistles and bells, and the lower income institutions like the ones we represent don’t get enough support from the federal government or from the states to make up for those inequities that exist in communities. So, its kind of a perpetuation of the inequality.”

Flores said he has dedicated himself “to helping communities that are least able to extricate themselves from poverty. To me education is the main avenue out of poverty.”

HACU has been instrumental in addressing some of those issues, particularly through its scholarship programs. Flores said when he first took the helm, the organization had about 110 members “and now we represent 572 Hispanic-serving institutions. Our renewal rate for membership is 96%.” HACU provides student scholarships, internships, retention and advancement programs, as well as career development opportunities for educators.

Transforming lives

Promoting cultural awareness and encouraging collaboration are also among the practices that Dr. Thomas Parham, president of California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH), considers critical to the institution. Parham, who began his presidency at CSUDH in 2018, is a veteran leader in higher education — he previously served as vice chancellor for student affairs at UC Irvine. Parham, a licensed psychologist and a prolific researcher, said he strives to develop a “culture of care” with dedicated faculty and staff all working toward the success of their 16,000 students.

As president, Parham believes another important function of his leadership is to “dissipate silos” in order to achieve a cohesive environment that promotes innovation. “Probably one of the most innovative techniques I’ve tried … is to develop an e-sports academy,” he said, noting that there has been some skepticism that the campus “must be into gaming.” He counters with an explanation that e-sports “is not an outcome but a strategy” that incorporates coding, math, critical thinking, logic and other courses in an interdisciplinary curriculum.

Other innovations include programs in the college of education “training teachers on how to be more culturally competent,” and the Male Success Alliance specifically designed for males of color.

Designated a Hispanic Serving Institution, CSUDH has 89% students of color — with the largest demographic group being Hispanic and the second largest being African American. Parham pointed out that 66% of CSUDH students are first-generation, 70% are Pell eligible, and 60% of the Pell cohort “have an expected family contribution of zero, meaning they are so economically challenged they don’t pay any tuition.”

“I’m acutely aware of the challenges that a lot of our students have,” acknowledged Parham, adding that he has noticed — as Crazy Bull also pointed out — that a number of marginalized students do not believe they belong in a university setting.

“We have a large contingent of students who, through no fault of their own, have not been really prepared through their high schools or community colleges to manage … the hard rigors of a university curriculum,” Parham explained. “That underscores one of the fundamental issues that we have to worry about, which is helping to create a profound sense of belonging.” Parham believes initiatives like Early Start and innovations such as e-sports are designed to keep these students engaged.

Parham said he measures his institution’s overall success by “how much access we can grant and how many lives we can transform.”