In 1958, when Charles J. Brown graduated from high school as class president, he decided to enlist in the U.S. Army.

“My family were very poor — they didn’t have scholarships or student loans back then — and my only way of getting out of Mississippi was through the U.S. Army,” said Brown.

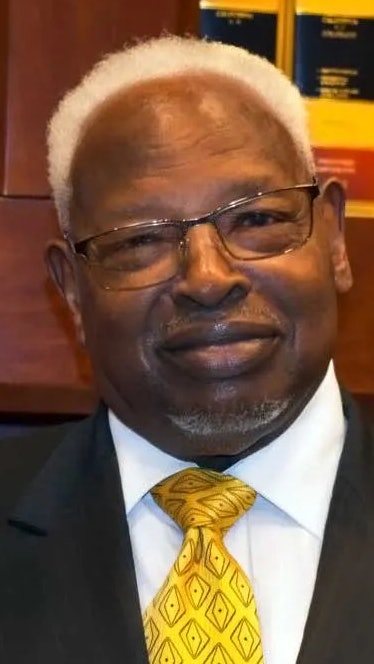

Charles J. Brown

Charles J. Brown

“If they saw one [of us] by himself, he was in trouble. That was the state of Mississippi,” said Brown. “This society, especially in the South, were prone to make sure in no form or fashion that you were equal.”

The Army presented a very different kind of life. By the time Brown enlisted, the U.S. armed forces had been integrated by Executive Order (EO) 9981, signed by President Harry S. Truman on July 26, 1948. Black troops served alongside white, Latinx, and Asian troops, training together and fighting together.

“We were one United States Armed Forces,” said Brown. “It just so happened that we were Black, Caucasian, and Hispanics.”

But while EO 9981 mandated “equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin,” Brown said that when it came time for leave, fun, or socialization, the men he trained alongside all went their separate ways.

“The community we was in dictated where the white guy went, where the Black guy went, where the Hispanic guy went. We mighta got on the same bus, but when we got off, we got off in the direction of our ethnicity,” said Brown. “But when you were back on the post, it was who had the commanding officer rank that would prevail. It had nothing to do with your color.”

The dichotomic experience was representative of a country still settling scores of a violently racist past, long before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed and longer still before segregation was demolished in practice. EO 9981 was signed despite an unwilling public, legislatorial protest, and even outcry from military leaders themselves. Yet, its signing signaled a new era for America and Americans. It paved the way for Brown v. Board of Education, which desegregated education, and proved without a doubt that society can work and live together regardless of race.

“This is one of the really important parts of the EO,” said Dr. Matthew Delmont, the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History at Dartmouth and author of Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad. “It gave those activists in different organizations a chance to say, ‘If the military can do this, despite all the challenges they said they would encounter, other parts of American society can also integrate.’”

A long and arduous process

The process of undoing segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces did not happen smoothly or even all at once. It took until 1954, after the Korean War, for all Army units to fully integrate, and even longer for the Army Reserves and National Guard. The process was deliberate, conscious, and took a tenacity that is still being applied to the integration of other marginalized groups into the military today.

“Groups that are marginalized fight to become soldiers, and they turn around and say, ‘We’re serving, sacrificing — why aren’t we allowed civil rights?’” said Dr. Peter Mansoor, retired colonel in the U.S. Army and the General Raymond E. Mason Jr. Chair of Military History at The Ohio State University. “Any group that’s marginalized, if it serves in the military, has a case to be made for civil rights. This is what happens, and it’s happened again and again throughout American history.”

The effort it took to make EO 9981 happen, and the effort it continues to take to preserve the military and other institutions as equitable organizations, is a lesson that can continue and be learned today, said Delmont.

Service member Harry Brooks, who achieved rank of Major General, boards an H-23 helicopter after discussion with Capt. Deral E. Willis during the Vietnam War.Harry Brooks Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

Service member Harry Brooks, who achieved rank of Major General, boards an H-23 helicopter after discussion with Capt. Deral E. Willis during the Vietnam War.Harry Brooks Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

For decades, civil rights activists like A. Philip Randolph and Mary McLeod Bethune applied pressure to integrate the military. Despite propaganda that espoused otherwise, Black people had been fighting and participating in the American military since the American Revolution. But even after the creation of all-Black units in 1866, their members also known as Buffalo soldiers, Black men were barred from combat assignments. Instead, they became labor battalions, often working menial tasks under the command of white officers.

“The officer corps was overwhelmingly white, except for some lieutenants and corporals,” said Dr. John H. Morrow Jr., professor emeritus at the University of Georgia and co-author of Harlem's Rattlers and the Great War: The Undaunted 369th Regiment and the African American Quest for Equality.

“The white officers, especially senior officers, were rabidly racist. Their objective was to demean the [Black] men and make certain that these units did not do well in combat, because if they did, that would upset the segregationist apple cart,” said Morrow. “A big concern was making sure that segregation and white supremacy was preserved in the U.S. It would not do for the Black units to do well in combat, because that would give people ideas.”

The 369th Infantry Regiment of all-Black soldiers were sent to France during World War I because the armies of the European allies were in personnel crisis after almost four years of fighting. Under French command, the 369th became combat soldiers, “fighting in the French Army, earning the respect of their French peers, and were heavily decorated by the French — a number of the men got a distinguished service cross,” said Morrow.

But upon their return to the U.S., their accomplishments and experiences were practically nullified by white hate. Lynchings and white violence against successful Black veterans, businesses, and neighborhoods grew, leading to the Red Summer of 1919, which was closely followed by the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921.

“Southern senators and politicians said, ‘The uppity colored men coming back think they’ll change things,” notes Morrow. “They wanted to destroy any notion in Black people’s minds that they had done well, that they had served well. There was no reward, simply punishment and repression.”

Black soldiers, said Morrow, became so angry with the way they were treated after World War I, “they vowed things had to change.”

The opportunity for change came in the next world war. World War II, which the U.S. joined in 1941, proved costly, and once again a personnel crisis motivated General Dwight D. Eisenhower to finally allow Black soldiers to serve openly in combat, said Mansoor.

“You’d have a company of four platoons—three would be white, and one would be Black. And they did very, very well,” said Mansoor. “The platoons were a huge benefit to the U.S. Army in Europe, and a lot of white officers and soldiers could see that there was no difference between Black and white soldiers.”

Yet, again, upon their return to America, these Black veterans who had proven themselves in combat on land, air, and sea were subjected to the horrors of racism. In 1946, Sgt. Isaac Woodard was riding a Greyhound bus home to South Carolina. He asked the bus driver to stop for a restroom break. The driver refused, and instead dropped him off at the next stop where white police were waiting. Woodard, still wearing his U.S. military uniform, was arrested, beaten, and blinded.

Truman finally takes a stand

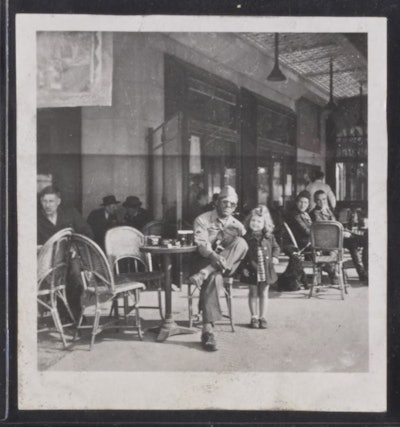

WW II Veteran at sidewalk café with five year old Yvette Doray, Paris, France.Ellis L. Ross Col- lection, Veterans History Proj- ect, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

WW II Veteran at sidewalk café with five year old Yvette Doray, Paris, France.Ellis L. Ross Col- lection, Veterans History Proj- ect, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

Delmont said the segregated military was an embarrassment to the U.S. on the world stage, and that weighed heavily on Truman as cold war dynamics began to fester at the end of World War II.

“It was something other nations used as propaganda against the U.S.,” said Delmont. “To have a segregated military as he was trying to persuade other nations pursuing independence that the U.S. was the model to follow — it was embarrassing.”

But ultimately, one of the biggest reasons Truman decided to sign EO 9981 was simply his reelection.

“Truman was afraid of losing the presidential election,” said Dr. Jo Von McCalester, a lecturer in political science at Howard University. “He understood [how to] utilize the Black vote.”

McCalester said that Truman knew EO 9981 could potentially gain him Black voter support, but it would also come into direct conflict with a large portion of his political party, the Democrats. But he signed the measure anyway, and in so doing began the cultural shift of the political parties.

“The immediate reaction to the Executive Order was the Dixiecrats,” said McCalester. “Literally the same year (1948), Strom Thurmon and his supporters left the Democratic National Convention, became Dixiecrats, and then joined the Republican Party.”

EO 9981 “sparked the idea that a new day, a new view, of how the country is to address and deal with race had come,” said McCalester. “It wasn’t easy, and it didn’t mean that white society was gonna jump on it and run with it — absolutely not — but the challenge could be made.”

The aftermath of EO9981

By the time Brown enlisted, the Army had solutions to deal with racism among the newly integrated ranks, something they called “squash it,” said Brown. Conflicts were put out quickly, potentially involving reassignment or court martialing. When he became a sergeant, Brown flavored his command with humor, forcing squabbling men to hug each other and share a tent in close quarters.

“’Every time I see you, you better be smiling,’” Brown recalls telling the soldiers, with a laugh. “’You training for combat and you gonna fight each other before you get there? What you gonna do to the enemy, take off running?’”

In his 11 and a half years in the Army, Brown said he never experienced incidents of racism; although he knew they happened in other units. He went on to serve in Vietnam, earning several medals including two Purple Hearts and Bronze Stars for Valor, later sharing his stories with the History channel’s Vietnam in HD in 2011. Wounded by grenade shrapnel in his legs, Brown was honorably discharged from the Army in 1969 and returned to the one place he never thought he would: Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He got his degree from William Carey University and went on to help the poor and veterans gain the skills and resources needed to find work.

Now 85, Brown spends a lot of time at the African American Military History Museum, housed in Hattiesburg’s former USO Club for Black soldiers stationed nearby at Camp Shelby. Museum director Latoya Norman said she learns new stories every day about the bravery of Black men and women who served and continue to serve in the U.S. military.

“I know, coming into this atmosphere, working in a museum that honors African Americans in the military, having a grandfather who served in WWII and a brother in the marines, you feel like you know the sacrifices that soldiers make.