Before Heman Sweatt, an African-American from Houston, won his lawsuit to attend the University of Texas School of Law, Carlos Cadena, a Mexican-American from San Antonio, was among its brightest students. Cadena graduated summa cum laude from the law school in 1940, a decade before Sweatt’s lawsuit forced UT to open its graduate and professional programs to Blacks.

Unlike African-Americans, Mexican-Americans have been able to attend the university since it was founded in 1883. Though they were treated like second-class citizens in Texas, they were considered White under state law.

The different legacies of Blacks and Latinos at UT provide a window into Texas’ complex racial history as the U.S. Supreme Court considers the Fisher v. the University of Texas affirmative action case. The court will decide whether the university’s admission policy discriminates against Whites. But more than a century ago, when the Texas Constitution of 1876 created UT (“a university of the first class”), only Whites could attend the university. A separate university was to be created for “coloreds.”

It’s important to understand the different histories of Blacks and Mexican-Americans at the state’s flagship university, says Dr. Rodolfo O. de la Garza, a political science professor at Columbia University and former professor at UT.

“What it really illustrates is the most powerful difference between being Black and Mexican in Texas,” de la Garza says. “The Black experience was uniform. It didn’t matter what you were if you were Black. That isn’t true for Mexicans. If you were affluent, you were treated differently, you thought of yourself differently.”

“Within a year of it opening, there were Mexican-American students from Laredo at UT,” says de la Garza. “But they were essentially from Laredo’s elite families. … There was a section of South Texas that survived [with land and wealth] during the worst days of Mexican discrimination.”

Dr. Rolando Hinojosa-Smith, the Ellen Clayton Garwood Professor of Creative Writing at UT and an acclaimed novelist, received his bachelor’s degree from the university in 1953 — a year before Brown v. Board of Education desegregated undergraduate programs at the university. Theophilus Painter, the defendant in Sweatt v. Painter, was the president of UT.

Many of the Mexican-American students there when Hinojosa-Smith was a student were from Laredo, the Rio Grande Valley and El Paso in West Texas, he says. Hinojosa-Smith is from the tiny town of Mercedes in the valley. He had served three years in the Army during World War II and attended college on the GI Bill.

Hinojosa-Smith’s brother-in-law and his brother-in-law’s brother received their law degrees from UT in the ’30s, he says. “The valley is very different from the rest of the state because the people there had been on both sides of the Rio Grande,” he says, referring to the divide between Texas and Mexico.

People had been there a long time, dating back to 1750, when the Spanish, who controlled the area at the time, conducted the first census. To the west, El Paso was the first Spanish colony in what is now Texas. Their longevity in Texas explains why so many Mexican-Americans from the valley, Laredo and El Paso attended UT. The students were overwhelmingly middle class, though some relied on the GI Bill to pay for their education, Hinojosa-Smith says.

But they still faced racial discrimination, though Hinojosa-Smith says he didn’t experience discrimination. “There was a co-op where kids from the valley stayed,” says Hinojosa-Smith. “It was called the HA House, for Hispanic American. … The HA House was strictly Mexican-American.”

Mexican-American social clubs like the Laredo Club organized events for the students, providing camaraderie and a respite in an environment that wasn’t always welcoming.

“Even though you were middle class and could go to UT, there was still racism,” says de la Garza.

Citizenship, whiteness and UT

The university doesn’t know how many Mexican-Americans, Asians or other people of color have attended UT because it didn’t keep racial and ethnic data on students until the 1970s, says Gary Lavergne, UT director of admissions research and author of Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall and the Long Road to Justice.

More importantly, he adds, “the complexity of the state’s racial definitions made it impossible to sort out.”

“Plessy v. Ferguson is the best treatment of how arbitrary racial classification can be,” he says, referring to the 1896 Supreme Court case that upheld state segregation laws. Homer Plessy was one-eighth Black, enough to be classified as Black under Louisiana law.

“As a matter of fact, [how to determine racial classification] came up in the Fisher argument. The chief justice said, ‘Suppose you have someone who is one-eighth Hispanic. What is that person supposed to check?’ We are still living with the ambiguities of [racial definition] and it kind of confuses any investigation into the issue,” Lavergne says.

The point is particularly relevant to Mexican-Americans in Texas, who became White by virtue of citizenship, first when the Republic of Texas was founded in 1836 and later when Mexico lost a swath of its territory in a war with the U.S. in 1848.

“The Supreme Court ruled that non-Whites couldn’t be citizens, but by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, [Mexicans] were White,” Lavergne says, because they were granted citizenship under the peace agreement. At that time, citizenship was synonymous with being White.

The Mexicans who now found themselves under U.S. rule were told they could keep their property, but over time, historians say many lost their land because of discriminatory laws and legal challenges to ownership. The treaty stripped American Indians of the citizenship they had under Mexican law. Life for Blacks didn’t change much, though. More than a decade earlier, the 1836 Republic of Texas Constitution, written following independence from Mexico, repealed Mexico’s anti-slavery laws and enslaved once-free Blacks.

Although Mexican-Americans were considered White, they were subject to Jim Crow-style treatment. The state’s public education system was segregated, with Mexican-Americans attending schools, in most cases, with other Mexican-Americans. The state approved separate schools for Blacks.

One of the most important legal victories for Mexican-Americans in Texas was in 1954: Hernandez v. Texas. The case was decided two weeks before Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled that separate but equal schools were unconstitutional. Hernandez successfully challenged practices that routinely excluded Mexican-Americans from state juries, preventing them from being tried by a jury of their peers. The argument hung on this line argument: Although they were legally considered White, Mexican-Americans were treated as “a class apart.” That is, they did not fit into a legal structure that was focused on Black and White. Therefore, the lawyers argued, Mexican-Americans should be protected by the 14th Amendment, as Blacks were.

The lawyers who brought the case to the Supreme Court were Mexican-American graduates of the UT law school: Carlos Cadena, Gus Garcia and James DeAnda. Cadena and DeAnda later were among the founders of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF).

Nationally, the Hernandez decision was eclipsed by the Brown decision. “Our Constitution, our institutions were designed to exclude Blacks. Mexicans weren’t part of the ballgame,” de la Garza says, explaining why Brown was the more prominent case. “They were a tiny population [then].”

But in Texas, both legal cases mattered, and still matter today. They capture the distinct legacies of African-Americans and Mexican-Americans at UT.

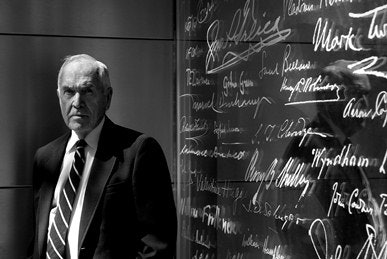

Dr. Rolando Hinojosa-Smith received his bachelor’s from UT in 1953 — a year before Brown v. Board of Education.

Dr. Rolando Hinojosa-Smith received his bachelor’s from UT in 1953 — a year before Brown v. Board of Education.