Some people are undoubtedly wondering why United States Vice President Kamala Harris chose the Fisk Memorial Chapel as the venue from which she offered last Friday's remarks in support of the Tennessee General Assembly's then-recently expelled Democratic Reps. Justin Pearson and Justin Jones.

Jones has since returned to the Capitol following a unanimous vote by the Nashville Metropolitan Council to reappoint him as an interim representative. Pearson, too, has been reappointed via vote by the Shelby County Board of Commissioners. Dr. Crystal A. deGregory

Dr. Crystal A. deGregory

But the fate of “the Justins” was uncertain when Republican lawmakers expelled them as a comeuppance for their part in a March 30 nonviolent protest in support of gun control. With Rep. Gloria Johnson, who also faced expulsion but against whom the vote failed, the trio, dubbed "The Tennessee Three," unsurprisingly garnered immediate support from The White House.

But why did they appear on the ground at Nashville's Fisk Memorial Chapel?

Most obviously, the choice was likely related to Fisk University, the oldest institution of higher learning in Nashville, being Jones' alma mater. He shares the claim with Black luminaries stretching from Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois to the late Rep. John Lewis. As the home to the nonviolent Black college student protests of the modern Civil Rights Movement, Lewis joined a pantheon of Fisk student activists, including the 2022 Presidential Medal of Freedom Awardee Diane Judith Nash.

Dedicated in January 1866 as a freedmen's school, Fisk has a long, storied tradition of nonviolent Black activism. Those efforts may begin inside Fisk's classrooms but stretch far beyond the campus and its environs to business and industry, the arts and humanities, as well as politics and the public square.

It was twenty years ago this coming fall that, as a Fisk freshman, I first lifted my eyes to read the chapel’s legend that has, since 1892, summoned listeners inside: "Arise shine, for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee."

Railroad stock left by General Clinton B. Fisk, one of the school's founders and its namesake, had matured to more than $30,000 following his death in 1890. The equivalent to more than $990,000 today, his widow and family allocated those funds to construct the Fisk chapel.

Following a budgetary shortfall, the chapel’s handsome balcony, which extends on three sides, was saved by the intervention of a white missionary woman-teacher who contributed her personal funds and others who donated to ensure its erection.

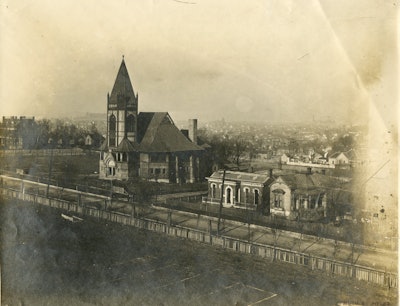

As the spiritual and religious centerpiece of the campus community, not only is the Fisk Memorial Chapel a superb example of High Victorian picturesque architecture, it has been home to some of the most prolific speakers in all of American history. Its roll call is a "who's who" that includes Tuskegee University founder Booker T. Washington, suffragist and civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Thurgood Marshall, the first Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice.

For several generations of Fisk students and students on its sister-historically Black college and university (HBCU) campuses, including Vice President Harris and Pearson's alma mater Howard University in Washington, D.C., weekly "Chapel Hour" was as sacred as it was mandatory. Whether religious or secular in scope, it was during these roughly hour-long meetings that students were imbued with a sense of social responsibility and communal belonging—whether they realized it or not. FISK MEMORIAL CHAPEL (1892). Named in honor of Clinton B. Fisk, major contributor to the construction fund. The edifice is a superb example of High Victorian Picturesque architecture. It serves as the location of many campus functions.Courtesy of the Fisk University John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library Special Collections, Fisk Photograph Collection.

FISK MEMORIAL CHAPEL (1892). Named in honor of Clinton B. Fisk, major contributor to the construction fund. The edifice is a superb example of High Victorian Picturesque architecture. It serves as the location of many campus functions.Courtesy of the Fisk University John Hope and Aurelia E. Franklin Library Special Collections, Fisk Photograph Collection.

By the time I was a student at Fisk during the early 2000s, only some chapel events were compulsory for some students. Still, virtually all instructors offered some credit for attending lectures and other public functions of cultural significance. So as an undergraduate, I saw everyone from South African Bishop Desmond Tutu to two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Dr. David Levering Lewis and poet Nikki Giovanni in the chapel.

As an alumna, preeminent Black historian of the twentieth century, Dr. John Hope Franklin, Washington, D.C. power-broker Vernon Jordan, and civil rights activists Diane Nash and Myrlie Evers-Williams joined the ranks of prodigious speakers I witnessed in the Fisk Chapel.

The point is not that we're unappreciative of Vice President Harris' choice to choose the Fisk Memorial Chapel but that HBCU campuses, their chapels, and pulpits have been sites of discussion, debate, and, most importantly, of nonviolent Black protest for well over a century.

Whether the eyes of the world are upon us in contemplation of topics at the top of the news cycle or mainstream media focuses on our representative challenges rather than celebrating our exceptional contributions to the Black freedom struggle—or outlets choose to ignore us altogether—we at HBCUs have long prayed with our hearts while moving this nation and the world towards a more perfect freedom with our minds, mouths, hands, and feet.

Now, thanks to the courage of Jones, Pearson, and Johnson, and countless other everyday Americans, many of them only children, a new generation of Fiskites can lay claim to continuing the storied traditions of our holy grounds. Because the most beautiful architectural designs of historic HBCU buildings are not made of brick and mortar or stone or stucco. The truest beauty of HBCU architecture has been, and will always be, the determination of Black people.

Dr. Crystal A. deGregory is the director of the Mary McLeod Bethune Center for the Study of Women and Girls at Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach, Florida. Her forthcoming book “The Greatest Good: Nashville’s Black Colleges, Their Students, and the Fight for Freedom, Justice, and Equality” is under contract with Vanderbilt University Press.