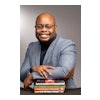

In this season of ongoing celebrations, as we remember and reflect on the life and legacy of the late civil rights icon and leader, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Dr. Ronald W. Whitaker, II

Dr. Ronald W. Whitaker, II

Upon arriving in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 3, 1968, King was physically exhausted, weighed down by the burdens of leadership, and grappling with his lifelong struggle with depression. What is less widely known; however, is that King arrived in Memphis the day before his assassination, in the midst of a fierce storm and tornado warnings.

Indeed, King began his address to the crowd that evening with the words, “I’m delighted to see each of you here tonight in spite of a storm warning. You reveal that you are determined to go on anyhow. Something is happening in Memphis, something is happening in our world” (King, 1968). The storm King referred to that night symbolizes the socio-political storms that many Black scholars are currently navigating, as turbulence and change rage both inside and outside of campus environments.

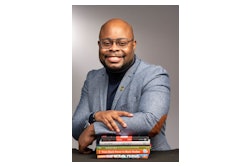

Twelve years ago, in his book Strategic Diversity Leadership: Activating Change and Transformation in Higher Education, DEI scholar and thought leader Dr. Damon A. Williams issued a warning to academics and campus leaders about what he termed a "perfect storm." Dr. Adriel A. Hilton

Dr. Adriel A. Hilton

Williams writes: “The degree shortfall, along with changing demographics and an increasingly turbulent political landscape, has created a ‘perfect storm’ for leaders contemplating the role of diversity in higher education. To understand and overcome the challenges of this perfect storm, academic leaders must fundamentally reframe how they approach issues of diversity in our colleges and universities” (Williams, 2013, p. 31).

According to Williams, several “critical pressures” are fueling the perfect storm on college campuses. However, one of the most concerning threats, particularly for those advocating for authentic justice within higher education, is the ongoing legal and political assault on diversity and affirmative action. Following the second presidential election of Donald J. Trump, we have already begun to see the promised reverse of DEI initiatives within some of the country’s largest corporations. Similarly, as argued in this article, there is a continued effort to dismantle DEI programs in higher education.

Yet, on the evening of April 3, 1968, King was not only confronting a storm; he was also addressing a deeper, more pervasive, and pernicious problem, which he framed as a “sickness.” After introducing the historical context and poetic reflections on the movement, King did not mince words, asserting, “the nation is sick. Trouble is in the land; confusion all around.”

At the core of King’s assertion that “the nation is sick” was his identification of three major evils: (1) “the evil of racism,” (2) “the evil of poverty,” and (3) “the evil of war.” As a leading figure within the Black Prophetic Tradition, King understood that a nation rooted in systemic injustice, economic inequity, and racial oppression is inherently “sick.”

Unfortunately, as we write this article today, we are still confronting a serious “sickness” on campuses. Systemic equity gaps and disparities continue to persist across demographic groups, particularly impacting our most vulnerable students. Additionally, the rising cost of college tuition disproportionately affects students from lower-income families, further exacerbating the barriers to higher education. Economic inequities within higher education also highlight broader systemic inequalities, such as the underfunded programs designed to support vulnerable student populations (Mitchell, Leachman, & Masterson, 2018).

Despite the rhetoric suggesting that we have entered a “post-racial” society, studies present counternarratives expose widening gap on racial inequality in higher education. In the face of the storms and sickness described in this op-ed, it is easy to feel discouraged and downtrodden.

This is why we draw from the wisdom and courage of King, who, even in the midst of adversity, possessed the uncanny ability to speak the painful truth while simultaneously offering hope for a better tomorrow. For example, after asserting that the nation is sick, King reminded us that “only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.”

We believe this is the focal point of King’s message. Specifically, despite the dark storms and sicknesses in society and within the academy, this may be the moment for us as Black scholars and leaders to shine. Our call to shine is not rooted in the pursuit of promotions, tenure, senior administrator positions, or the building of our professional brands. No, we argue that we must authentically shine in order to critically reflect on the issues plaguing campuses and, more importantly, to find the courage to stand for truth and justice.

We shine when we, as King urged America to do on April 3, 1968, remind campus leaders and colleagues to be “true to what you said on paper.” Each college has a mission statement, vision statement, code of ethics, values, and strategic plan that underscores the importance of moral behavior. Therefore, when we receive reports and data suggesting that vulnerable populations are being targeted within social catalytic spaces on college campuses, it is an urgent call to remind leadership to adhere to the values stated in official documents, such as websites, marketing materials, and other institutional communications.

Lastly, we shine when we confront the existential realities of our existence. As those closest to King have shared, on the night of April 3, 1968, he knew his time on earth was short. Similarly, despite our accolades and titles, our time in academia is relatively brief, and we must decide what legacy we wish to leave. In honoring our ancestors, elders, students, and communities we serve, we must stay focused on the promised land—a promised land rooted in justice, democracy, freedom, safety, security, opportunity, and solidarity. As such, we must not lose hope in the belief that things will get better for “we as a people!”

In closing, do not give in to pessimism and fear. Instead, choose to shine. By doing so, we might not only be saving the soul of our institutions of higher education, but collectively, we might be saving the soul of this nation.

Dr. Ronald W. Whitaker, II, is a Visiting Associate Professor of Education at Arcadia University, Director of the MEd in Educational Leadership Program, and Co-Director of the Social Action and Justice Education Fellowship Program at Arcadia University. Additionally, Dr. Whitaker is an inaugural faculty fellow at Vanderbilt University for the Initiative for Race, Research, and Justice.

Dr. Adriel A. Hilton serves as Director of Programs, Transition and Youth Success Planning (staffing the Assistant Secretary of Juvenile Rehabilitation) in the Washington State Department of Children, Youth and Families. Most recently, he served as vice-chancellor for student affairs & enrollment management and associate professor of education at Southern University at New Orleans.