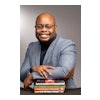

Dr. JT Torres

Dr. JT Torres

She was inspired by recent workshops and publications advocating for culturally responsive pedagogies, approaches that seek to make learning concrete, evoke emotion, and connect historical content to students’ lived realities.

But by the following week, she was on administrative leave.

Some parents expressed outrage. One called the lesson “retraumatizing,” another said it “evoked so many deeply hurtful things about this country.” The incident spread rapidly, picked up by conservative media outlets as another example of DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) gone wrong in the classroom. The teacher issued an apology, and the school later acknowledged that while the lesson was pulled from “reliable sources,” it “was not culturally responsive and had the potential to cause harm.” The San Francisco Chronicle covered the full controversy here.

Even when we try to do everything right, teaching is hard. Inclusive teaching? That’s harder still.

To make matters worse, our missteps — especially when they touch on race, identity, or systemic injustice — don’t always stay in the classroom. In today’s political climate, they can be distorted, weaponized, and used in broader attacks on DEI efforts. Unfortunately, much of the conservative framing — that attempts to be more inclusive in our teaching will include flaws — is in fact a reality. The political motivations behind these attacks deserve serious scrutiny, but they are beyond what we can control in the classroom and what we must come to understand more clearly.

While inclusive learning is a science, inclusive teaching is more like a performance art.

Learning is predictable

Cognitive science tells us a great deal about how people learn. And the research supporting inclusive education is both robust and clear. Below are just a few examples.

Situational interest, a key driver of engagement, requires a sense of belonging. When instruction includes novel, emotionally or intellectually stimulating features, students show greater attention, motivation, and cognitive performance, particularly in STEM and technical subjects (see Guo & Fryer, 2025; Hidi & Renninger, 2006). Whether a particular situation arouses emotional or intellectual stimulation depends on whether students have a chance to connect with the learning environment in meaningful way. In other words, an inclusive environment increases the likelihood that students will be interested in the learning.

Meanwhile, experts have long recommended multiple, collaborative assessments to provide a more robust picture of student learning that accounts for differences in students’ strengths and backgrounds. For instance, research shows that collaborative testing not only improves scores and reduces anxiety, but also supports long-term retention and peer learning (see Cortright et al., 2003; Bloom, 2009). In other words, assessments that are equitable are also effective.

Finally, perceived relevance, a cornerstone of student motivation, is tied directly to cultural diversity in course design. Similar to situational interest, when students connect academic content to their own lives or real-world issues, they report greater satisfaction, engagement, and persistence. These results are especially pronounced in underrepresented groups (see Asher et al., 2023; Hunsu et al., 2017). In short: students learn more when they feel included, when they see their identities reflected in the material, and when their knowledge is assessed through more than one lens or opportunity.

But here’s where the gap opens. While science can explain how learning happens, it can’t script how we, as educators, should design and deliver every lesson. That’s because (especially inclusive) teaching is not just a technical application of best practices. It’s a deeply human endeavor: expressive, subjective, unpredictable, and relational.

And like any form of art, it does not land the same way with every audience.

Teaching is improvisational

This is why inclusive education is so difficult to defend and deliver. It demands more of us, not just technical expertise, but also emotional sensitivity. We must understand our content, yes; but we also need to understand our students, the histories they carry, the assumptions they face, and the power dynamics embedded in our institutions. These things can change from year to year. A joke that reliably resulted in laughter one year might result in eyerolls the next. A topic that excites some students might bore other students. A reading deemed appropriate in one institution might be seen as controversial at another.

We will make mistakes.

But inclusive teaching isn’t about being flawless. It’s about being reflective. When we misstep, it’s not a signal to retreat into silence or defensiveness. It’s an opportunity to listen, learn, and try again. Because our students are still there. Still watching. Still trusting us to make the classroom a place where they can show up fully and be seen.

Unfortunately, the political and media climate sends the opposite message: that a single mistake warrants the end of a career or complete cancellation of a person, program, or institution. The work we do to normalize the messiness of social interaction in our classrooms can help to normalize the messiness of social interaction beyond our classroom.

So how do we keep teaching as art, informed by science?

Below are a few evidence-based practices that are certainly not foolproof; however, these practices help ensure that even when mistakes happen, an inclusive environment can be sustained.

- Universal design

The more flexible and accessible our environments are by default, the less we need to play gatekeeper, counselor, or diagnostician. If we build adaptable structures from the start, fewer students will need to ask for special exceptions, and more will thrive on their own terms. For instance, when I assign a project in a class that does not have “written communication” as one of its student learning outcomes, I leave the decision to students as to how they materially develop their projects, including creating a video, audio, or written text. (Learn more about Universal Design for Learning) - Provide choice.

Extending the recommendation to prioritize universal design, when students have meaningful options for how to engage, demonstrate learning, or co-construct course content, we share both the labor and the love of the learning process. Choice builds metacognition, ownership, and the habits of democratic participation that education should model. (See research on student choice and agency) - Listen

Sometimes the best move we can make is to pause and take in what our students are trying to tell us through feedback, body language, performance, or even silence. Listening well doesn’t just build trust; it sharpens our assessment and helps us adapt to situations with meaningful intent. Many times, I had an activity or assignment planned, but after learning something about my students during informal conversation, I revised or scrapped the activity or assignment. (For a deeper dive, see Kate Murphy’s very enjoyable You're Not Listening)

Inclusive education will never be easy, and stories of missteps will continue being spun into justifications for undercutting higher education broadly. We must normalize mistakes and continue reflecting, learning, and prioritizing our students’ identities. The best way to do that is to invite students to the planning. Let them tell you ahead of time if something has the potential to land awkwardly or successfully. Give them a chance to give you a chance. When the classroom becomes a collective endeavor, mistakes and successes are shared and celebrated by everyone.

Dr. JT Torres is the director of the Houston H. Harte Center for Teaching and Learning at Washington and Lee University.