In January 1977, I began a faculty appointment at the Federal Executive Institute (FEI) in Charlottesville. The long, gray winters endured teaching political science at Syracuse University in New York propelled me to look southward, and FEI beckoned.

The thought of returning to the South was met with some trepidation but I decided to take a leap of faith. The reverence paid to “Mr. Jefferson” locally prompted me to pay attention to Virginia’s colleges and universities, several of which had begun to lay down markers.

I remain fascinated by how the higher education landscape has changed. Madison College now is highly competitive James Madison University. The former Northern Virginia campus of the University of Virginia now is George Mason University. Christopher Newport University, Old Dominion University and Virginia Commonwealth University — essentially commuter schools three decades ago — have undergone major transformations.

For the most part, these changes have been substantive. They could not have happened without strong leadership in the executive and legislative branches of government, but also the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) and of course, institutional leadership.

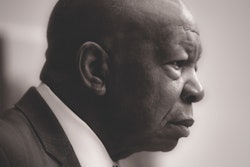

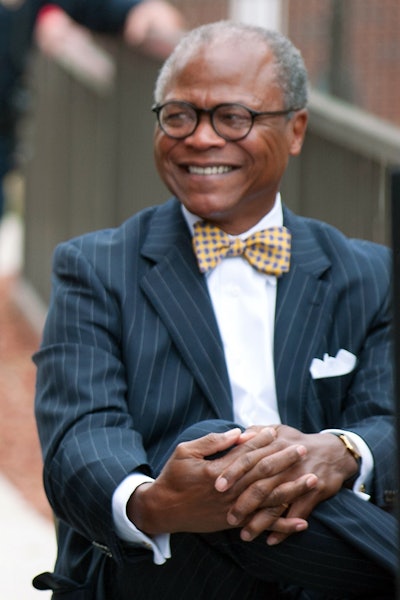

Dr. Alvin J. Schexnider

Dr. Alvin J. SchexniderHaving worked at public universities in Virginia and North Carolina, I believe that the heterogeneity of Virginia’s higher education institutions is a major asset. Virginia, unlike North Carolina, has a coordinating body rather than a comprehensive university system.

In Virginia every tub stands on its own bottom. Schools with strong leadership and engaged governing boards are able to make significant progress by carving a distinctive niche, and attracting students and faculty who are drawn to its mission, unique character and array of degree programs.

Virginia’s universities and colleges are major assets that should be deployed to combat the lingering effects of slavery.

Virginia is the birthplace and the incubator of America’s original sin. While several public universities bear the names of slaveholders — Madison, Mason, Washington — all carry the stain, and its most prominent schools were built by enslaved people. Virginia’s colleges and universities supported slavery, benefited from it and sought to justify it.

Faculty promoted theories alleging the intellectual inferiority of Black people, and wrote textbooks and articles packed with lies. Snatching Black bodies from graves for medical research and the systematic conscription of Black men in prison to be used as guinea pigs — a practice that continued well into the 20th century — are among the worst crimes against humanity.

The degradation of human beings found support in the classroom, laboratories, law schools and medical schools of Virginia’s colleges and universities. The neighborhoods surrounding state-supported academic medical centers are among the most disadvantaged — with ZIP codes documenting Third World health resources, life expectancies and infant mortalities — but whose citizens derive little direct benefit from their presence.

Virginia’s colleges and universities must be intentional about addressing the residual effects of slavery. Racial disparities in education, health, criminal justice, housing and income are obvious areas where they can make a difference.

For example, North Carolina’s community colleges will provide specialized training for law enforcement agencies in all of the state’s 100 counties to eliminate racial disparities in policing.

Amazon represents a half-billion dollar state investment. Higher education institutions must be intentional that African American graduates benefit from this venture in ways that exceed increases in an institution’s budget.

Applying the intellectual capital and technical know-how of Virginia’s colleges, universities and academic medical centers to addressing its most intractable racial problems is not asking too much.

Education has been and remains the great equalizer in American society. Virginia can confront the horrors and evils of slavery by being intentional about combating its residual effects. There are countless ways to contribute to the task.

Virginia Commonwealth University’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs sponsors annual symposia on race and society that spotlight selected public policy issues. Recently, UVA released a task force report that recommended 12 key initiatives to improve racial equity at the university. This is a laudable start, but the plan will help the university more than its neglected communities.

In this mea culpa moment, nearly every public, private and third sector organization in the country has issued a statement confirming its commitment to social justice. For many, the promulgation of carefully worded proclamations will be met with skepticism as mere platitudes.

Nearly 30 years ago, Judge A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., quoting U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, reminded Justice Clarence Thomas that “for millions of Americans, there still remain ‘hopes not realized and promises not filled.’” We dare not miss this opportunity — again.

This column initially was published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Dr. Alvin J. Schexnider is a senior fellow at the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges.