University of Maryland campus, Memorial Chapel.

University of Maryland campus, Memorial Chapel.

The University of Maryland's (UMD) The 1856 Project has released its first report covering the history of their institution and its intersection with slavery, Reconstructing the Truth. Its goal, stated in the report, is to become a “blue print for a richer understanding of generations of racialized trauma rooted in the institution.”

Findings include just under 100 known names of enslaved persons whose labor built UMD, an acknowledgement that the institutional founder and early donors were slaveholders, a better understanding of the vital role northern Prince George County played in the Underground Railroad, and the development of a map that identifies former homesteads and communities of freed Black people.

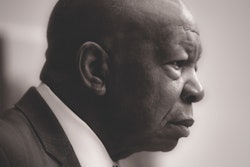

Lae’l Hughes-Watkins, co-chair of The 1856 Project and associate director for engagement, inclusion and reparative archiving, Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Maryland.

Lae’l Hughes-Watkins, co-chair of The 1856 Project and associate director for engagement, inclusion and reparative archiving, Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Maryland.

“The political environment we’re in now, it’s pushing back against the ideas of democracy—whose stories get to be told, who gets valued in this country—it’s turning us backward,” said Hughes-Watkins. “This project is a counter to that. We’re going to push forward and tell the stories that aren’t easy to tell.”

These stories are complicated and often traumatizing, Hughes-Watkins said, but their discovery can play a critical role in healing a racially stratified world.

“The project plays counter to dismantling of diversity, equity and inclusion, to this desire to silence, as we try to create a more diverse, equitable society,” said Hughes-Watkins. “It’s our own small way to ensure that all voices are heard, and all people are respected.”

The Xfinity Center on UMD campus, formerly the site of Eversfield plantation.

The Xfinity Center on UMD campus, formerly the site of Eversfield plantation.

Through the combined work of research students across the country, searching through hundreds of archival documents and collaborating with local organizations like The Georgetown Slavery Archive and the Riversdale Historical Society, The 1856 Project has been able to find and acknowledge a history that is often kept behind closed doors.

Hughes-Watkins acknowledged that UMD leadership’s complete support of the project, including funding, has made all the difference in the project’s success. It took a village, Hughes-Watkins said, from the interning students conducting research, to the advisory board and community liaisons, to create the report. And community involvement will be necessary as the project begins to move into its next phase, said Hughes-Watkins, which involves connecting with the descendants of enslaved workers.

In researching and publishing this report, UMD has joined over 100 institutions across six different countries, from Historically Black Colleges and Universities to Ivy League institutions as an established chapter of Universities Studying Slavery (USS), founded in 2014 at the University of Virginia (UVA). USS institutions share best practices and advice on how to reckon with the past, acknowledging how they benefitted from unpaid, slave labor, while working towards moral accountability in their present.

Dr. Kirt von Daacke, assistant dean and professor in the Department of History at the University of Virginia and early co-chair of the Universities Studying Slavery commission.

Dr. Kirt von Daacke, assistant dean and professor in the Department of History at the University of Virginia and early co-chair of the Universities Studying Slavery commission.

“These [reports and investigations] aren’t designed to make universities look bad. It’s universities that are unafraid to turn the lens onto their own landscape and past and understand how that process informs us about American history and helps us understand how our institution got to where it is today,” said von Daacke, adding that USS findings are “really important for the inclusive nature of public universities.”

USS member institutions may face challenges from anti-DEI legislation, said von Daacke, but the work they do is supported by collegiate mission statements: to educate and produce new knowledge in the name of education.

“All these schools with roots in slavery are entirely white, male institutions at their founding,” said von Daacke. “They’re not those schools anymore. Some of this is really important to understanding that history, because that makes it a more welcoming place to people who don’t look like the university’s first generation of students or founding fathers.”

Hughes-Watkins agreed.

“Students know that there’s no way an institution this old has no ties to slavery,” said Hughes-Watkins. “I think they appreciate when we engage in truth-telling, when we’re honest about the ugly, the painful. It helps them feel seen.”

Liann Herder can be reached at [email protected].