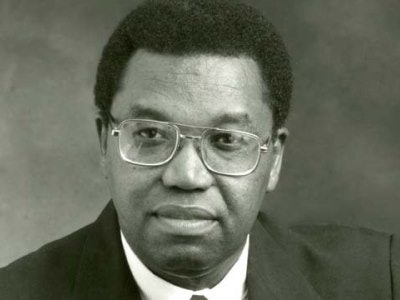

Dr. James A. Hefner was a champion for education of the masses, focusing most particularly on Blacks and historically Black institutions, although not to the exclusion of others.

Dr. James A. Hefner was a champion for education of the masses, focusing most particularly on Blacks and historically Black institutions, although not to the exclusion of others.Higher education administrators are mourning the loss of one of their veteran colleagues — Dr. James A. Hefner — who blazed an admirable trail in nearly half a century of service as provost of two institutions, president of two universities and adviser to scores of colleagues along the way.

Hefner, 76, who had most recently served as provost and vice president for academic affairs at Clark Atlanta University, died August 27, of cancer, at his home in Nashville.

At Tennessee State University, where he served as president from 1991 to 2005, a memorial service for Dr. Hefner on the campus was set for Wednesday. Last week, Jackson State University, in Mississippi, at which Hefner was president from 1984 to 1991, had a ceremonial ringing of its Centennial Bell, lowered its flag and held a moment of silence for faculty, staff and students in honor of his service.

Morehouse College, where Hefner had served as Charles E. Merrill Professor of Economics and dean of its Department of Business and Economics from 1974 to 1981, issued a statement calling him one of the “stars” of the historic institution. It noted Dr. Hefner, who later served on the college’s Board of Trustees, has asked that scholarships be established in his name and be awarded to outstanding students attending Morehouse and Tennessee State.

Throughout his career, Hefner, a North Carolina native who earned his bachelor’s degree at North Carolina A&T University (then College), used his college training as an economist to focus on Blacks and the nation’s economy. He saw an education as a ticket out of limited opportunity and poverty and dedicated his life to helping other promising people get tickets.

With the support of his wife Edwina, whom he met while in graduate school at Atlanta University, he used his training as an economist to help students as a teacher at Prairie View A&M and Florida A&M universities, as an academic planner and administrator at Tuskegee University, Morehouse, Jackson State and Tennessee State and Clark Atlanta. As he took on one professional assignment after another, he helped raise three sons, wrote books and papers about Blacks and the economy, and worked as a research associate at Princeton and Harvard universities.

All along the way Hefner mentored and, sometimes too often, found accessible funds to turn into scholarships for the promising of the next generation who just needed a hand.

Clark Atlanta University President Ronald A. Johnson, who took office this summer, calls Hefner “a hero to many.” Johnson, who counts Hefner as a mentor, said the veteran educator possessed a “moral compass that motivated him to ‘find a way or make a way’ for so many others.”

Dr. Bettye Clark, acting provost at Clark Atlanta whom Dr. Hefner called out of retirement earlier this year to take on part of his work, echoed others in characterizing her colleague.

Clark, who had served nearly five years as graduate dean at Clark Atlanta, said Hefner was “one of the kindest persons I ever worked with. Kind,” she said, “but stern,” explaining how both were admirable and respectable traits. “He was patient to hear your side. He was firm, in a good way. Even a ‘no’ is okay when he gives you his reasons.”

While his methods were not always clearly understood by those around him, Hefner was a champion for education of the masses, focusing most particularly on Blacks and historically Black institutions, although not to the exclusion of others.

“He [Hefner] was the consummate academician,” said Dr. Nebraska Mays of Nashville, a former administrator at Tennessee State and Fisk universities. “Understanding broad areas of academic activities and the faculty involved requires an administrator who not only understands the programs, but how to work with the faculty,” said Mays, a former senior vice president for academic affairs at the Tennessee Board of Regents, the state agency governing most state-controlled institutions of higher education, including Tennessee State.

Balancing those broad responsibilities is not an easy task for a president, said Mays. Hefner mastered the challenges over the years, he said, hitting a high point at Tennessee State in 1996 when he got TSU its first research-based Ph.D. program — successfully converting a psychology Ed.D. program. He had championed internal organization and collaboration between various schools and departments and cleared the myriad external hurdles posed by the state and other accrediting agencies.

Before he retired in 2005, the university had successfully initiated two more Ph.D. programs: one in biological sciences, the other in computer and information systems engineering.

Hefner’s appreciation for the First Amendment and importance of press freedom was far above that of many presidential peers. He was a reliable advocate for TSU’s student campus newspaper, The Growling Tiger, regardless of its reporting — good, bad or indifferent ― about his leadership. He saw the paper win numerous national journalism awards, sometimes based on its reporting stories that were accurate, yet unfavorable, about him.

Some people who worked with and watched Hefner fall victim to more than one “bad” story were at times puzzled over why he allowed such to continue. Those who knew him well said his tolerance of a free press was deeply rooted, stemming from his days as a student at North Carolina A&T University and member of its campus newspaper staff.

His reward was seeing many TSU campus paper staffers earn college degrees and get recruited for jobs in the news business after graduation or go to graduate school, outcomes that far overshadowed the “Dollar Bill Jim” stories that occasionally mocked his leadership.