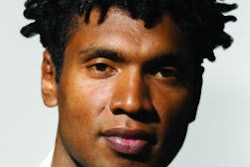

When Dr. Ned Blackhawk steps into the classroom, he never uses the term “discovery” when addressing the history of European contact with the indigenous peoples of this continent — and it’s not because he feels the pressure to be politically correct. “I try not to use the term simply because it is so loaded,” Blackhawk says. “I prefer ‘encounter,’ which suggests multiple worlds rather than singular ones. We live in an amazingly diverse world. Our society has always been diverse.”

The idea of diversity resonates beyond Blackhawk’s research and teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His life has and continues to be informed by diverse views, people and places. In addition to growing up in a multiracial Detroit community, his family made sure to connect Blackhawk to his Western Shoshone tribal roots with summer visits with his grandmother, Eva Charley, in Reno, Nev.

During his high school years, he dreamed of traveling, but plans for college needed to come first. Blackhawk’s mother graduated from Antioch College in Ohio, and his father was one of the first Native Americans to enter graduate school at the University of Nevada, Reno. However, wanting to make his own way, Blackhawk dropped in on a college campus in Canada.

“I ended up in Montreal at McGill University,” he says. “It was one of the craziest and best decisions of my youth. I literally arrived on campus without a place to stay since I had mistakenly assumed that all freshmen received dorm assignments as they did in the United States.”

Though he initially set his studies on international relations, Blackhawk found himself drawn closer to history. “Over time I came to see history as a politicized subject, and I became particularly aware of the absence of indigenous people and their history in Canada and the United States,” he says.

This issue of indigenous history became a living reality for Blackhawk when two Quebec Mohawk communities resisted the development of a golf course on their ancient burial grounds. The Oka Crisis, as history recalls it, was a military standoff that lasted 78 days during the summer of 1990. Eventually, the Mohawk prevailed and the golf course was never developed. Watching Mohawk history collide with the present had a deep impact on Blackhawk’s sense of Native identity and pride. And in the years since he has come to understand the need for greater inclusion of indigenous histories in the classroom because misunderstandings and conflicts between Native people and Whites are not issues of the past.

Though he is part of a very small group of tenured Native American history professors, Blackhawk is recognized by his peers for making significant contributions to a field of study that is in dire need of diverse Native perspectives. Dr. Ben Marquez, a UW political science professor, says Blackhawk’s first book, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Harvard University Press 2006), has established him as a leading authority on Native history and won him a half dozen professional awards.

“Blackhawk’s ability to interpret the web of social relations among Native peoples, military power, and European encroachment in North America is superb, and offers important insights on the complex and often tragic history of indigenous people,” Marquez says.

With a wife and two children, Blackhawk has come full circle in realizing that his research is making needed impressions on his students. “I try to challenge people’s perceived understandings about American history, and expose students and readers to the cycles of change and disruption that accompanied European settlement and expansion in North America. Indians are, of course, central to such a reassessment.”

Title: Associate Professor of History and American Indian Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Education: Ph.D., History, University of Washington; M.A., History, University of California, Los Angeles; B.A., Honours History, McGill University