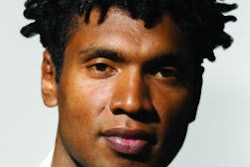

Underachiever is not a term one would use to describe Dr. Carlos Rinaldi Ramos. Late in 2007, at 32, he was feted at the White House with the government’s highest honor for young researchers: the Presidential Early Career Awards for Scientists and Engineers. A year ago, Rinaldi was promoted to full professor of chemical engineering at the University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez.

But in high school, guidance counselor Carmen Sánchez-Quintana scolded him for not living up to his potential. “She said, ‘You could have been the top student in the class if you’d worked on it,’” Rinaldi recalls. “I promised her I would get a 4.0 in college. Then I went to college in Puerto Rico and, every semester, I would go back and show her my transcript. And I kept my promise.” And more.

The undergrad valedictorian went on to earn two master’s degrees and a Ph.D. in chemical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Straight out of MIT, he snagged an assistant professorship at UPR-Mayagüez. He delayed a promotion to seek a National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development grant for nontenured assistant professors. In 2006, the NSF rewarded him twice: with a $411,521 CAREER grant and a $1.15 million Nanoscale Interdisciplinary Research Team grant.

Both fund Rinaldi’s research into magnetic nanoparticles, fluids composed of tiny magnets “about a thousand times smaller than the diameter of your hair,” he says. The particles can be moved around in a magnetic field and used as contrast agents in a magnetic resonance imaging machine. Rinaldi and his co-investigators hope magnetic fluids will be used to treat cancer.

“In targeted drug delivery, it can be used to concentrate the particles in a certain part of the body to minimize the area affected by (chemotherapy),” Rinaldi says. “Imagine the particles are in a tumor and you apply a magnetic field to them. In an oscillating magnetic field, particles respond by dissipating energy and heating the tumor — and, hopefully, destroying it. It’s called magnetic fluid hyperthermia. It’s something that’s been shown in animals. We’re looking at it so it’s suitable for clinical trials on humans.”

Rinaldi traces his passion for research to his undergraduate days. Thanks to an NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates and an MIT summer research program, he spent two summers at Cornell University and MIT. The research bug bit.

Rinaldi spread that passion to include academia as well as the community. He runs a summer program for precollege teachers who spend several weeks in UPRM labs learning about research. Then the teachers take the experiences back to their classrooms. Rinaldi also leads a summer NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates — the same program that inspired him as an undergrad.

“The whole department is extremely proud of all the contributions he has made to the department — and not only related to his research endeavors, which are pretty unique for a young faculty member,” says Dr. David Suleiman Rosado, director of UPRM’s chemical engineering department. “He has been a true mentor with the graduate students.”

Rinaldi also zealously prods students to go to graduate school. In a field where Hispanics and women are scarce, his advisees are mostly Hispanic women. UPRM’s chemical engineering department has a rare demographic: 70 percent of the undergrads are women.

“Hispanics are underrepresented as scientists, but if you look at the projection in population, half the population in 50 years is expected to be Hispanic,” Rinaldi says. “If we don’t get these really bright students getting advanced degrees in science and engineering, the United States will have a hard time keeping its role as a leader in science and engineering.”

He prods because he knows the impact of a mentor’s faith. Sánchez-Quintana, his high school counselor, remembers her faith that inspired Rinaldi to a perfect grade-point average in college: “He was like a pearl that is buried under a lot of soil that people can’t see.” Rinaldi remembers. The dedication for his doctoral thesis began like this: “This thesis is dedicated to Carmen Sánchez for making me realize that I am solely responsible for achieving my true potential.”

Title: Professor of Chemical Engineering, University of Puerto Rico-Mayaguez

Education: Ph.D., Chemical Engineering Practice, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; B.S., Chemical Engineering, University of Puerto Rico Mayaguez