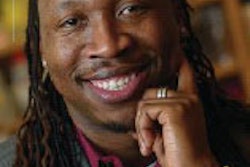

Most scholars who study the Indian subcontinent during the colonial era focus on relations between the British rulers and their South Asian subjects. Dr. Kris Manjapra has instead concentrated on interactions between German intellectuals and their South Asian peers. “My interest is in the study of colonialism and how it brings together different communities on a global scale,” explains Manjapra, a tenured associate professor of history at Tufts University.

“I’m interested in the forms of migrations, of exchange, of racialization and exploitation that come out of a modern colonial regime.”

In his 2014 book, Age of Entanglement: German and Indian Intellectuals across Empire, Manjapra reveals and explores two-way exchanges between colonial subjects of the British and citizens of another European country. Between the 1880s and 1940s, nationalist members of both groups found they had a common interest in challenging the British Empire’s dominance.

After World War I, the nationalist leader of Calcutta University sent young academics to Germany to study the

sciences, Manjapra says. They returned to India as top-notch scientists and established academic departments based on the German model.

Ideas flowed in the other direction, too. Manjapra says Indian nationalists visited Germany, including Rabindranath Tagore, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature 1913. He gave lectures and read his poetry to German audiences.

Dr. Ayesha Jalal, the Mary Richardson Professor of History at Tufts, says Manjapra, 36, has had a significant

impact on colonialism studies and transnational history, which explores the sharing of ideas between countries.

“His contributions really are outstanding there for somebody so young. He has made a mark in the field with his ways of conceiving transnational intellectual history, which are innovative and very, very solid,” says Jalal, MacArthur “genius” award winner and one of Manjapra’s mentors.

Manjapra brings an international background to his work. He was born in the Bahamas, to an Indian father and

Afro-Caribbean mother. Manjapra grew up in Canada before coming to Harvard University to earn his three degrees. After earning a Ph.D. there, he arrived at Tufts in 2008.

Already, Manjapra’s scholarship has left an imprint on Tufts’ curriculum. He and other faculty members created a

colonialism studies program that began last fall.

Manjapra says the program’s courses represent “a different way of studying international relations and

globalization ” because they “look at the question from the perspective of the colonized.”

Manjapra taught a first-semester course on the history of plantations, which he says were a new way of organizing land, labor and capital when they started.

“That invention travels from its epicenter in the Caribbean and the Americas across the world. It travels all

the way to Asia by the time of the 19th and 20th centuries,” Manjapra explains.

That course reflects the direction of Manjapra’s research, who is working on a book, tentatively titled “Plantation Empires.” Once again, he is exploring exchanges between diff erent parts of the world — agricultural crops, in this case.

Manjapra has traced, for instance, how growing indigo moved from India to the American South and then back to India. Similarly, the cultivation of the rubber tree was transplanted from Brazil to Sri Lanka and Malaysia.

Sums up Manjapra: “It was the global circuit of colonialism that made it possible.”

Title: Associate Professor, Department of History, Tufts University

Education: A.B., history, Harvard University; M.A., history, Harvard University; Ph.D., history, Harvard University

Age: 36

Career Mentors: Dr. Sugata Bose, Harvard University; Dr. David Blackbourn, Vanderbilt University; Dr. Ayesha Jalal, Tufts University

Words of Wisdom/Advice for New Faculty Members:

“A book by Parker Palmer says the art of being an effective teacher is the art of being present to your students. I firmly believe that.”