Dr. John Silvanus Wilson Jr., who is guiding the nation’s only African-American men’s college, says the future of HBCUs is at risk if the colleges don’t figure out how to appeal to students.

Dr. John Silvanus Wilson Jr., who is guiding the nation’s only African-American men’s college, says the future of HBCUs is at risk if the colleges don’t figure out how to appeal to students.

His mantra, “Toward Capital and Character Preeminence,” is an initiative aimed at transforming the historic college into a world-class campus, while simultaneously producing a generation of men who will go on to become change agents like so many of their predecessors.

“Preeminence in capital and character is a powerful combination seldom exhibited by institutions of higher education,” says Wilson, who stepped down as executive director of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities in 2013 to lead the nation’s only African-American men’s college.

“So we are looking to increase institutional capital enough to have a sustainably world-class living and learning environment, and enhance institutional character enough to reliably produce more graduates who will help heal the world in distinctive ways,” he says. “And because no college or university that we know of has ever simultaneously realized both capital and character preeminence, that means we are setting out to do what has never been done before, at least not on the scale we envision.”

Philadelphia to Morehouse

It’s an ambitious undertaking, but Wilson isn’t short on ideas. In fact, he had been actively looking for ways to transform his beloved Morehouse ever since he journeyed south from Philadelphia to Atlanta in 1975 to enroll at the HBCU as a freshman.

It was at the Salem Baptist Church, located in a small suburb outside of Philadelphia, where Wilson first learned about the small, liberal arts college founded in 1867. The church’s pastor, Rev. Robert Johnson-Smith, was a devoted Morehouse man, as were his two sons.

“I think he talked about Morehouse at least as much as he talked about Jesus,” says Wilson with a laugh. “As a result, our church became a pipeline for Morehouse, because he used to talk about this place that was especially made for us.”

But shortly after he arrived to campus, Wilson became frustrated by how the campus was managed. There were long lines to register for classes and even longer lines at the financial aid office.

A chance encounter during his sophomore year with Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, the towering Black preacher, educator and social activist who presided over Morehouse for 27 years before retiring in 1967, was significant. The brush with Mays likely planted the seeds that ultimately led Wilson to believe that he could someday help to take Morehouse — an institution that had produced graduates like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and theologian Dr. Howard Thurman — to even greater heights.

The year was 1976, and Mays had decided to make a run for the Atlanta school board, an odd choice to some, given his prominence throughout Atlanta and indeed the nation. But “he didn’t take the campaign for granted,” recalls Wilson. “He asked for volunteers to campaign, and I was among the volunteers passing out leaflets and fliers to various communities.”

Shortly after winning the election in a landslide, Mays returned to a dormitory lounge at Morehouse to thank the student volunteers for helping him achieve victory.

Armed with a copy of Mays’ autobiography Born to Rebel for him to sign, Wilson positioned himself at the end of the receiving line and eventually struck up a conversation.

“He asked me, ‘How’s it going? Do you like it here at Morehouse?’” Wilson recalls. “And I said, ‘Actually Dr. Mays, I love it, but I don’t always like it.’”

Mays listened very carefully, and, when Wilson finished talking, he looked the youngster in the eye and offered him a very clear directive: “He said, ‘I hear you. I want you to finish Morehouse. I want you to get some more education and experience and I want you to come back and make a difference.’”

White House to Morehouse

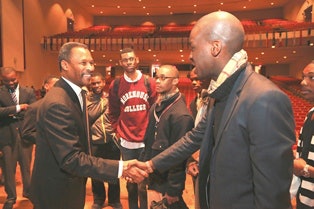

And that’s precisely what Wilson has done, walking away from a coveted position within the Obama administration to help lead one of the nation’s most storied institutions of higher learning.

“I chose Morehouse over the White House, but I still retain a great relationship with the White House, [evidenced] by the fact that my first graduation speaker and the first person I handed a Morehouse degree to was Barack Obama,” says Wilson. “When the call came from Morehouse, of course it’s an honor to lead your alma mater.”

During his time at the helm of the White House Initiative, Wilson helped increase the federal flow of funds to HBCUs. Before President Obama took office, less than $4 billion was allocated to HBCUs, and by the time Wilson left his post, the pool had increased to more than $5 billion, according to the White House Initiative on HBCUs.

“By that single measure, I think it’s beyond debate that we were effective,” says Wilson, whose research on HBCUs while serving as a professor of education at George Washington University and dean of the university’s Virginia campus caught the attention of Obama.

But Wilson, who earned master’s degrees in theology and education, respectively, before enrolling in a doctoral program in education, was also admonished for some of his critiques of Black colleges.

“I think it’s safe to say I was necessarily candid and I was that way because I just felt this sense of urgency and still feel it,” he says. “I think we’re going to see more volatility that might lead to closures and I chose to be very candid about those danger signs, and it was not appreciated by everyone. And yet, now that I’ve shifted from the White House to Morehouse, if anything, I feel even more urgent about our need to embrace change.”

Wilson says that the reduction in the number of women’s colleges over the past 30 years — down from 300 to about 50 — could become the fate of all HBCUs, if colleges don’t figure out how to appeal to students.

Several decades ago, about 80 percent of African-Americans in the country were educated at HBCUs, but today that number is roughly around 11 percent, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, with for-profit institutions like the University of Phoenix leading the way in enrolling the majority of Black students.

“The bottom line is that our value proposition is insufficiently clear to too many people,” says Wilson, who also worked as an administrator at MIT and served for many years as the president of the Morehouse Boston alumni chapter. “And I believe that those of us who clarify our value proposition first and clearest will be built to last. Those that are not able to clarify their value proposition run the risk of having to merge, run the risk of having to close or run the risk of extinction. I’m determined that Morehouse will be built to last.”

Almost two years on the job, Wilson has stabilized the school’s finances, beefed up efforts to recruit more students and has made some impressive hires, including luring Dr. Marc Lamont Hill — one of the nation’s most visible Black intellectuals — away from Columbia University.

Dr. Bryant Marks, the executive director of the Morehouse Research Institute and an associate professor of psychology, says that Wilson’s energy and vision are refreshing.

“The landscape of higher education is changing very quickly relative to previous eras,” says Marks, who is also an alumnus of the college. “President Wilson has a unique combination of experience, knowledge and skills that will significantly contribute to Morehouse not only surviving, but thriving, during a time when colleges and universities face unprecedented challenges.”

For Wilson, who graduated in 1979 with a group of classmates who went on to achieve prominence — such as filmmaker Spike Lee, Homeland Security Secretary Jeh C. Johnson and Martin Luther King III, the eldest son of the slain civil rights leader — the opportunity to lead the institution has been deeply gratifying.

“I am absolutely happy,” he says with a smile. “Not every day is an over-the-top joy, but most are. I have a big ambition for this place, and if you’re trying to do a great thing in a world-class way, it can be nothing but fun.”

Jamal Eric Watson can be reached at [email protected].