Jelani Day, wearing his white lab coat after graduating from Alabama A&M University.

Jelani Day, wearing his white lab coat after graduating from Alabama A&M University.

She wanted to be wrong. How could her former student—the brilliant, kind leader, the one who helped quieter students find their voice—suddenly be dead? Day was only 25 years old, one week into classes as a speech pathology graduate student at Illinois State University. Blakeney-Billings had written his recommendation letter for entry into the program.

Day studied under Blakeney-Billings as an undergraduate at Alabama A&M University. When he earned his white lab coat at graduation, a fellow student told Blakeney-Billings that Day wore the coat all the way back to his dorm, as though he would never take it off.

Blakeney-Billings remembered Day calling to tell her of his acceptance to ISU. She made Day promise to do well and make her proud. He promised.

It was the last time they would speak.

In the six months since his disappearance and death, Day’s mother, family, and friends have insisted that the Bloomington Police Department dragged their feet during the investigation. With the help of Black civil rights organizations and leaders like the Reverend Jesse L. Jackson, the Day family is urging the public and police departments, especially those in predominately white neighborhoods, to pay more attention to cases of missing people of color.

Day first went missing on Aug. 24. The following day, his mother, Carmen Bolden Day, filed a missing person’s report to the Bloomington Police Department (BPD). On Aug. 26, BPD issued a public missing person’s bulletin. That same day, Day’s car was discovered in Peru, a town roughly an hour north of the Bloomington-Normal area, concealed in a wooded area near the Illinois Valley YMCA. Its license plates had been removed.

In the days that followed, Day’s school lanyard, wallet, and iPhone were found spread out between the YMCA and the nearby Illinois River. The ISU police cooperated with BPD, canvassing the dormitories and classrooms for clues.

On Sept. 4, a body was found on the bank of the Illinois River, about one mile upstream from the YMCA. It took almost three weeks for police to confirm the body was Day.

Dr. Diane Jeanne Blakeney-Billings and her former student, Jelani Day.

Dr. Diane Jeanne Blakeney-Billings and her former student, Jelani Day.

BAMFI has taken on the task of helping Black families seek justice for their missing loved ones, covered in the HBO Documentary Black and Missing.

“There was a lack of urgency demonstrated in Jelani Day’s case. That seems to be the norm with missing people of color, male, female, or child,” said Wilson.

On Oct. 25, the coroner announced Day’s cause of death was a drowning, which Wilson said has clear implications.

“That preconceived notion, that he died because of drowning—are they trying to say he committed suicide?” asked Wilson.

Bolden Day insists that her son was a strong swimmer, a member of his high school swim team, and he gave no indication he was experiencing suicidal ideation.

Being Black in a Predominately White Community

The twin cities of Normal and Bloomington Illinois, as they are called by locals, are majority white. Normal, where ISU is located, is 90% white. The Black population at the school is only about 9%.

In 2019, Black students at ISU gathered in protest after the Black Homecoming Committee posted to Twitter about the difficulties they were encountering during planning. The protesting students alleged that ISU’s diverse student populations were tokenized and called for greater transparency and support.

Eric Jome, ISU director of media relations, said that administration met with students many times to keep the dialogue open and to implement changes that addressed their concerns.

“We had a number of efforts to increase diversity on campus and create a more welcoming atmosphere. It continues to be something we work on,” said Jome.

After the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Jome said more students came forward to express their “concern about things in the community, on campus.”

Dr. Venus Evans-Winters

Dr. Venus Evans-Winters

“It was another traumatic event, with a lot of unanswered questions to the exact circumstances,” said Jome. “We as an institution tried and continue to try to support the students throughout. Our counseling center and our multicultural center became an important point of contact for students.”

Dr. Venus Evans-Winters, a former professor of education at ISU, said while she was there, she experienced racial slurs and microaggressions both on and off campus.

“I’ve only been called a nigger in my adult life in the city of Bloomington,” said Evans-Winters. “I don’t believe I reported it. It’s so commonplace," she said, adding that she and her Black colleagues "didn’t become accustomed to it, we just adapted to it.”

Evans-Winters found out about Day’s case, like many, through social media.

“How are universities going to protect our Black students, especially in cities in towns where there’s a history of racial tension and the direct, interpersonal, interracial conflict,” said Evans-Winters. “These universities have a responsibility, just like a parent does, to help protect their students from any harm or injury, psychological or physical.”

The Case Today, Six Months Later

The length of time between Day’s body being found and his identification is a point of frustration for Day’s family. The Federal Bureau of Investigation did not get involved in the investigation until after Day’s body was identified. According to WGLT, an NPR affiliated station at ISU, Peru Police asked the FBI to take the lead on Day’s case in late October, but that request was denied.

By December, the FBI and cooperating police departments had formed the Jelani Day Joint Task Force (JDJTF) and offered a $10,000 reward for information about what happened to Day.

State Senator Elgie Sims, a Democrat representing the Chicago area, has introduced SB 3932, which, if it passes, will amend the Missing Persons Identification Act to require medical examiners and coroners to contact the FBI if a body remains unidentified after 72 hours.

Bolden Day reached out to the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, an international civil and human rights organization founded by Rev. Jesse Jackson. In December, civil rights attorney Ben Crump, who represented the families of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery, joined the Day family at a press conference, where he accused the investigators of failing to make Day’s case a priority, and, by ruling his death a drowning, ignored the possibility that Day was a victim of homicide. Crump said he wants the FBI to examine Day’s case as a possible hate crime.

BAMFI, Bolden Day, Jackson, and Crump are working to keep Day’s story in the news. There is still a racial disparity when it comes to solving missing persons cases quickly, as demonstrated by the media's most recent focus on the case of Gabby Petito.

The fascination with Petito’s disappearance is an example of the missing white woman syndrome, a phenomenon in the media and society to only pay attention to missing persons when they are young, white women. That fascination enables resources. Not just drones and K9 units but money, manpower, and heightened national awareness. In the end, the search for Petito and her killer, Brian Laundrie, uncovered the remains of nine other missing people.

Wilson credits Petito’s father, who, while searching for his daughter, urged members of the media to turn their spotlight on other cases, particularly those of missing people of color.

“I think as a society we all have to check our biases, whether its conscious or unconscious, and recognize that these are valuable members of our community,” said Wilson.

Jelani’s Legacy

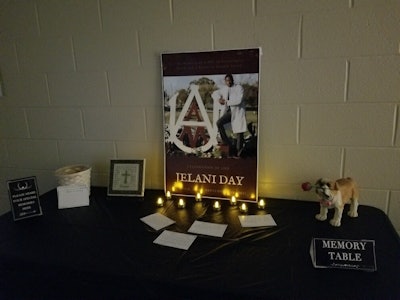

The memory table set up outside the Speech Language Pathology Office at Alabama A&M University.

The memory table set up outside the Speech Language Pathology Office at Alabama A&M University.

A similar service was held at Alabama A&M on the same day in Normal, Alabama. Outside her office, Blakeney-Billings set up a table for students, faculty, and staff to come by and write down their thoughts. The table stayed up for several weeks, because, Blakeney-Billings said, she couldn’t bear to take it down.

Speech language pathology is a small program at Alabama A&M, its students and faculty become a "close-knit” family, said Blakeney-Billings. Together, they have made their way through the grief.

Dr. Charles H.F. Davis III, an assistant professor in the Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education at the University of Michigan said there was a time not so long ago that universities were considered "in loco parentis, that they had a responsibility to care after folk’s children," he said. "That question still remains with regards to how graduate students may be somewhat different than undergrads, of course. And I think for me, the level of responsibility is the extent to which the institution can use its power and its resources in support of finding answers.”

Blakeney-Billings recalled the old saying: it takes a village to raise a child. She wondered if Day missed that village when he went away.

“We should open the discussion about how we can help these students more. I don’t care if they’re 21, 22—to me, that’s a kid. They go away to college, they don’t know anybody, and they get roped into the wrong situation,” said Blakeney-Billings. “This is a tragedy that should have never happened. I hope that people never forget there was a young man named Jelani Day, who had a very bright future ahead of him.”

Liann Herder can be reached at [email protected].