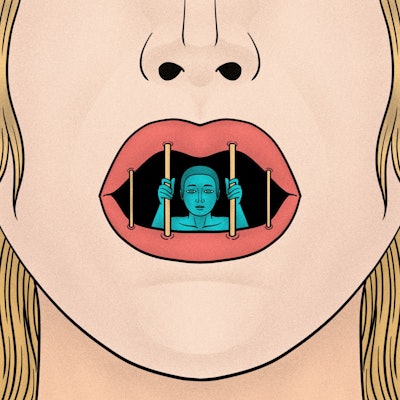

Throughout the years, Dr. Sandra Caron and Deborah Mitchell began to notice a certain trend each time they spoke to classes about sexual assault. Directly after the discussion, or perhaps days later, a student would come forward and disclose their experience of being assaulted. More often than not, Caron and Mitchell noted, these students would use the following phrase: “I’ve never told anyone this but…”

“We basically became a safe haven,” says Mitchell, who, as a former police sergeant and sexual assault investigator at the University of Maine, knows firsthand just how many campus assault cases go unreported to the police.

“We’ve spent decades telling women to seek help, seek support,” said Caron, a professor of family relations and human sexuality at the University of Maine’s College of Education and Human Development. “How is it — especially with the #MeToo Movement that started in 2017 and really amplified this idea of seeking help — that we still have women who hold on to this pain in silence?”

That was the central question she and Mitchell sought to answer in their recent study, “‘I’ve Never Told Anyone’: A Qualitative Analysis of Interviews With College Women Who Experienced Sexual Assault and Remained Silent,” published in the journal Violence Against Women. They wanted to know not only why students didn’t report their assaults to the police but why, according to one study, a third of victims chose not to tell anyone at all.

Though such students were difficult to find, Caron and Mitchell eventually interviewed 15 college students, between the ages of 19-24, who had previously never shared their assaults (all of which happened more than one year before the interview) with anyone before the study. Throughout the many hours of those conversations, Caron and Mitchell said they began to notice 10 common themes resurface.

“It was almost like a broken record when you heard the different experiences that women had with sexual assault,” said Mitchell. “They would come up with almost the same 10 reasons why they didn’t report it to anyone.”

Most prominent in those reasons, they said, was self-blame, shame and guilt. Other reasons included wanting to pretend it never happened; fear of losing control of the situation; fear of not being believed; fear of getting in trouble (such as if they were drinking underage); avoiding stigma/labels; not wanting to get others in trouble (such as if they had teammates who were drinking); fear of losing someone (one feared her boyfriend would not believe her); and fear of being hurt (through retaliation).

“They were really self playing and weighing the consequences, and choosing to remain silent,” said Caron. “The complexity behind their decision to remain silent stood out. These women had many reasons, and it was so clear they thought this through. … But what really became very apparent was that women clearly blame themselves, and certainly society blames them as well.”

Nearly all the women interviewed said they had considered telling someone under the correct

circumstances, but quite often those circumstances never came, as people either didn’t ask questions when provided hints or they became uncomfortable and closed themselves off to the conversation.

In one example of the study, a student describes going to the nurse’s office, not long after her assault, stating: “I went to the health center to get tested for STIs and the nurse actually made me feel like a bad person for having had sex without a condom. I feel she missed an opportunity to ask me why I had sex without a condom. She shut me down and just added to my belief not to tell anyone.”

Dr. Sandra Caron, left, and Deborah Mitchell, right, present their research at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality in Montreal.

Dr. Sandra Caron, left, and Deborah Mitchell, right, present their research at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality in Montreal.Another student said she felt uncomfortable telling her sorority sisters because she felt they would not believe her. After an educational program on sexual assault, she remembered that “many of the girls rolled their eyes and talked about all those girls who falsely accuse guys.”

Those examples, according to the study, illustrate the need for universities and colleges to move beyond sexual assault prevention training to include sexual assault support that involves training students and staff on spotting signs of sexual assault and on knowing how to respond.

“They felt shut down by the other person,” said Caron. “They knew the other person wasn’t going to be receptive to hearing this tragic news, and that gives us a little piece of insight in terms of understanding that prevention work isn’t just about [educating] people about the myths and realities — you know the typical discussion. We need to go one step further, and we need to help people understand how we spot when somebody tells you something difficult, or what to do when you suspect something has happened to someone. That piece of training needs to be in there.”

Encouraging such survivors to come forward is not only important for the survivor’s mental health and ability to move forward, but it’s essential to holding perpetrators accountable, said Mitchell, adding that each unreported case only enables the perpetrator.

“These women did not hold the men who raped them responsible, and they don’t feel society does either,” said Caron, who noted that many women had resigned themselves to thinking “this is just what men do.”

That finding, said Caron and Mitchell, reemphasizes what past studies have found: that colleges and universities need to include men in the conversation — and that means early on, in middle school and high school.

“For the sake of their mental health, it is important that colleges and universities help sexual assault survivors break their silence and talk freely,” wrote Caron and Mitchell. “This will happen as they continue to educate others, break down stereotypes and myths, and help others understand sexual assault for what it is — an assault perpetrated by a person against another. The responsibility lies with the perpetrator and not the victim/survivor.”

Jessica Ruf can be reached at [email protected]