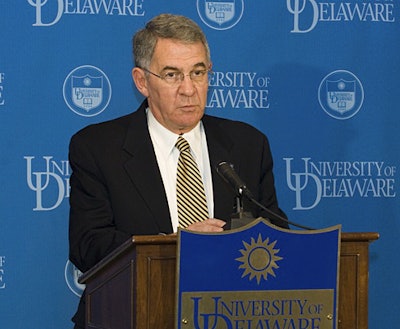

Former University of Kentucky President David Roselle

Former University of Kentucky President David RoselleFor college and university trustee board members, there’s typically no easy path to ensure effective governance and oversight of postsecondary institutions. In the first of a webinar series presented by the Pepper Hamilton law firm and Freeh Group International Solutions, expert panelists on Wednesday offered practical advice on how college trustee boards as well as individual trustee board members should conduct themselves.

In the webinar titled “Higher Education Oversight and Governance: Role of a College Board of Trustees,” former University of Kentucky president David Roselle said board members should largely devote themselves to the conventional wisdom of the phrase “noses in, fingers out,” an admonition “that [members] should be alert and they should sniff around, but they should not be getting their fingers in and meddle [with] things.”

“Management is responsible for day-to-day affairs; the board is responsible for provision planning and holding management accountable,” explained Roselle.

During the webinar, Roselle was joined by Barbara W. Mather, partner at Pepper Hamilton LLP and a former chair of the Swarthmore College Board of Managers, and Matthew Dolan, managing director of Freeh Group International Solutions (FGIS) and a former general counsel of the United States Naval Academy.

The Freeh Group International Solutions, an independent global risk management firm, was founded by Louis J. Freeh, a former director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and former federal judge. Last summer, Freeh and his law firm, Freeh Sporkin & Sullivan LLP, issued the independent report on Penn State University and the Jerry Sandusky child sex abuse cases.

Roselle, who also served as president of the University of Delaware, noted that it’s up to board chairpersons to effectively manage the boards on which they serve. “Another responsibility of the board … is [that it] needs to be evaluated …. The chairman of the board really has a big role in knowing who he has on the board,” he said.

Dolan told the webinar audience that boards have to be prepared to deal with crises and that requires plans on how to handle campus emergencies. “It could range from a natural disaster all the way to safety and security on campus. Many times though these crises in higher education we’ve seen are created by administration non-response to issues, such as sexual assault or NCAA violations or student misconduct,” Dolan said.

“The board’s role [in] proper governance and oversight will hopefully enable schools to avoid these kinds of crises,” he added.

Crisis management plans include provisions for emergency meetings such as having alternative sites at which they can be convened as well as established rules for conducting such meetings, according to Dolan.

“Make sure the board has their crisis action plan with regards to what kinds of meetings they would have, where they would have them, whether they would have to appoint an ad hoc committee to deal with any specific type of crisis. But all these types of issues can be identified and you can almost do the pre-planning for that crisis,” he explained. “But I always think you should know what the first five decisions are likely to be in any kind of crisis and how to think through those decisions for those specific crises.”

Mather offered advice about how colleges and universities manage risk areas such that institutions can avert a preventable crisis. “It’s the board’s responsibility to work with the president on a system of regular review of risks. That means that whatever the president and board agree are the primary risks need to be assigned with specific responsibility to an administrative member,” she said.

Ideally, that officer should be reporting through the administration about the risks to the board members “whose committee is assigned to the particular risk,” according to Mather.

Once the risks are identified, the board needs to monitor those risks, she said.

“Sitting down with the president, you need to figure out what the top 10 [risks] are that are truly critical for your institution and assign a reporting obligation to a particular board committee. That kind of reporting ought to be done on a regular cycle and on an as-needed basis,” she advised.

“The point is in order to be an effective board you need to make your own [risk] list for your own institution. You need to figure out which of these factors is important enough to be reviewed by the board and which belong to the administration and which may not belong on your list. And then you need to assign the responsibilities so that somebody is keeping track,” Mather said in her presentation.