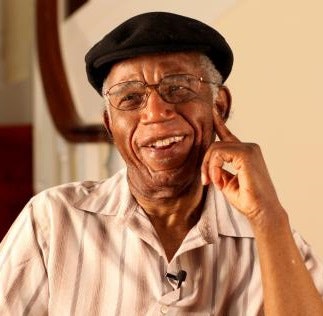

Acclaimed writer Chinua Achebe died last week at 82 years of age.

Acclaimed writer Chinua Achebe died last week at 82 years of age.It was not surprising that the passing of Chinua Achebe, the celebrated Nigerian-born writer, last week would stir numerous scholars as well as many others around the world to pay tribute to one of the most prolific authors of modern literature.

Best known for his first novel, Things Fall Apart, Achebe is regarded as a pioneer in modern African literature. His novels and essays critiqued post-colonial Nigerian politics and society as well as examined the impact of the West on Africa. Published in 1958, Things Fall Apart is said to be the most widely read work of African fiction, having sold more than 12 million copies. It has been translated into 50 languages.

On Thursday, March 21, the 82-year-old author died at a Boston-area hospital following a brief illness. At the time of his death, Achebe had been the David and Marianna Fisher University Professor at Brown University and he had recently published a memoir of his experience during the 1967-70 Biafran civil war in Nigeria.

At Brown and at numerous American colleges and universities, scholars marked Achebe’s death with an outpouring of praise and accolades for his achievement in literature. “Professor Achebe’s contribution to world literature is incalculable,” said Brown University President Emerita Ruth J. Simmons in a statement. Simmons was the university president when Achebe joined the Brown faculty in 2009.

“Millions find in his singular voice a way to understand the conflicting opportunities and demands of living in a post-colonial world. The courageous personal and artistic example he offered will never be extinguished. Brown is fortunate to have been his home,” she stated.

In Charleston, S.C., over the weekend, scholars attending the African Literature Association annual conference organized a special tribute to honor Achebe. Dr. Francoise Lionnet, director of the African Studies Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, said news of Achebe’s death brought a somber tone to the event. “People, especially the Nigerian scholars who knew him or who had been writing on his works, were very touched and moved. I saw some people crying,” Lionnet said.

“There was a sense that an era was ending because [he is] the first great African writer in the English language. … He is the one whose work has had the most impact, and he’s considered a great figure who inaugurates the field of Anglophone African literature,” she noted.

While traveling to Charleston on Friday, Dr. Kwame Dawes, the Chancellor’s Professor of English at the University of Nebraska, talked to Diverse about the impact Achebe’s work had on him as a literature professor. Dawes recalled that, as a youth growing up in Jamaica, reading Things Fall Apart left a strong impression on him long before he studied the novel in an academic context.

“I read Things Fall Apart when I was about 9 or 10 years old. … For me, it was an articulation of a culture that I understood. It just seemed to make sense as a work of literature that I felt had people like me in it [and] people who looked like me in it,” Dawes said, adding that he formally explored the book much later when he “was at university in Jamaica” studying African literature.

“At that point, my understanding and engagement with literature from Africa was immensely well-developed. … And Achebe’s book remained fascinating,” he said.

Dawes noted that he has long enjoyed teaching Things Fall Apart to undergraduates. He said the story of the Igbo warrior Okonkwo who struggles to live with British colonial rule in Nigeria has been one that the literature professor “never had problems with students being drawn into it and being able to discuss” in classes.

“Achebe’s novel is tried and true. First of all, it’s a very conventional story and it’s really beautifully written,” Dawes said. “Of course, the good news is that many of my students have read it in high school. It’s one of the few books I can teach in African literature where students have had prior experience with it.”

Dr. Greg Carr, an associate professor of Africana Studies and chair of Afro-American Studies at Howard University, recalled that, while it took more than a decade for Things Fall Apart to gain enough popularity and critical acclaim to become a widely studied novel in the U.S., it has managed in more than five decades to stand favorably alongside other classic novels in modern world literature, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.

“When you read his five novels, including Arrow of God, A Man of the People, and Things Fall Apart, what Achebe’s really doing is grappling with a fundamental question of how do Africans shape the modern world. And he does it in a way that forces his audiences to deal with an Africa as a complex idea and not just a simple stereotype,” Carr said.

Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, who was the founding chair of the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, was one of Achebe’s closest friends. Having met the writer in the 1960s at the end of the Biafran war, Thelwell was partly responsible for bringing Achebe to UMass-Amherst where he held a joint faculty appointment in English and Afro-American Studies from 1972 until 1976.

“Achebe was the most principled, most consequential, most committed and the most visionary Black person of his generation,” says Thelwell, who was invited by Achebe to give the opening address at the University of Nigeria on February 12, 1990, in honor of Achebe’s 60th birthday. “He was a triumph of the human spirit and the person I admire beyond any other human being I’ve ever met. My admiration for him is totally unconditional, both as a writer and as the most decent and honorable human being.”

Thelwell said he last spoke to Achebe about a month ago. And though Achebe had been a paraplegic for more than 30 years, “I never heard a complaint from him,” Thelwell says.

Jamal Watson contributed to this article.