There is considerable research generated about African Americans in higher education, specifically faculty. In fact, most studies concerning African Americans have focused on the retention of students or faculty (Wolfe & Dilworth, 2015). Yet there is little research on the underrepresentation of African American community college trustees. While much of the existing research suggests that increasing the number of faculty and administrators of color clearly has a positive effect on educational quality and student achievement (Fujimoto, 2012), the reality is that trustees can have a greater impact on policy, strategic goals, and eventually can lead the most dramatic change of vision within our institutions.

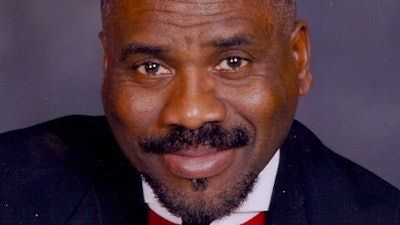

Carl B. Smalls

Carl B. Smalls

Having an advocate or mentor is critical

We found that the presence of a mentor in the life of the trustee was critical to the participants’ successful selection or election as trustee. For some, it was a political figure, for others, it was a local businessperson, or board colleague. Regardless of the mentor’s profession, what was obvious was that the participants had someone coaching, advising, or guiding them and networking on their behalf.

Community or public service experience was essential

Having community or public service experience was more important than one’s political affiliation. Research revealed that all but one of these award-winning colleges had a board-influenced diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) mandate. The research demonstrated that valuing those not like you cannot be forced and must become part of the culture of the college if we are to achieve true equity and inclusion. Trustees reported their college also broadened the definition of diversity to include opinions. We noted a commonality among all the participating trustees was that it did not matter how one defined underrepresentation, the institutional system (or process) would protect the system rather than diversify trustees, leadership, or faculty. Additionally, trustees had become leaders in the quest for equity and were informed advocates for all experiencing marginalization. Their colleges are leading the way, openly sharing models that embed diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Recommendations for practice

Data-based best practices were identified to develop a roadmap for a more diverse equity-oriented college. These recommendations include:

1. Expanding the definition of diversity to include opinion, fostering a climate of equity, civility, and inclusion that is welcoming and values everyone.

2. Before pursuing a trustee role, potential trustee candidates need to be intentional to gain meaningful experience by volunteering or serving on community boards, such as the YMCA, Urban League or NAACP, local boards, or faith-based organizations.

3. Equity is a clear part of the vision and mission of the college. Also, the institution’s DEI officers are most effective when having a dotted line relationship to the board of trustees and regularly reported to trustees on goals and progress.

4. Trustees need to intentionally develop policies supporting DEI and receive updates reviewing academic and administrative goals/actions on DEI efforts.

5. Trustees (and their institutions) will benefit when they participate in DEI professional development, encourage fellow trustees to serve on the ACCT Diversity/Equity Committee, and support professional development opportunities of college personnel.

6. Trustees should intentionally place measurable expectations and hold leadership accountable for hiring/recruitment practices, and conduct celebrations of diversity advocates/champions.

7. Trustees should establish a diversity advocate function on the board and receive reports on all hiring, recruitment, and interview processes.

8. Institutions should create a Senior Leadership Council to reinforce diversity, equity, and inclusion strategies as imperative business drivers.

9. Institutions should form campus resource groups where virtual spaces can be created for all to feel safe and share authentic experiences.

Dr. Carl B. Smalls serves as associate professor, accounting, business administration and global logistics, and as coordinator of inclusion and impact at Guilford Technical Community College (NC).

Dr. Terry Calaway is president emeritus, Johnson County Community College (KS). He serves as chair for the Community College Leadership Program (CCLP) Advisory Board and professor of practice, department of educational leadership, College of Education, Kansas State University.

Dr. Margaretta B. Mathis serves as senior director of the John E. Roueche Center for Community College Leadership, graduate program director and professor of practice, CCLP, Kansas State University.

The Roueche Center Forum is co-edited by Drs. John E. Roueche and Margaretta B. Mathis of the John E. Roueche Center for Community College Leadership, department of educational leadership, College of Education, Kansas State University.