Mr. and Mrs. Johnson are proud parents of third grader, Mason. He has excelled in school, academic competitions (spelling bee), and sports (particularly tennis). He has been one of the top performing students every year of his short educational experience. Lately, they have been surprised and concerned about Mason complaining about being Black, a slave, and a ‘bad boy.’ He has begun to rebel, to act out. Full of anger and embarrassment, he stormed out of class when his teacher said that slaves were good ‘workers’ who learned a trade. The distortion and the whitesplaining have been promoted and condoned by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis. The parents just read that Black teen suicide has increased significantly in recent years. Thus, they are not only concerned about his current state of mind but how this and related experiences will affect him later. They are so worried that they are exploring homeschooling as an option; this option has increased among Black families seeking to protect themselves from miseducation and discrimination.

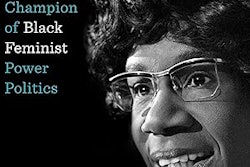

Dr. Donna Y. Ford

Dr. Donna Y. Ford

School counselors can serve as a gateway to providing all students with opportunities that will help them toward academic success, socio-emotional development, and college and career readiness. Furthermore, school counselors can help students access resources needed to achieve a well-rounded pre-K-12 school experience to be prepared for college, careers, and adulthood. The school counseling profession has to actively break down barriers and systems that exclude “certain” students and create ways in which all students get the assets needed to achieve success in school. In other words, we must decolonize school counseling and culturize the profession, specifically to address the needs of every student, regardless of race, ethnicity, zip code, etc.

In one of our previous Diverse op-eds, we discussed the need for more Black school counselors to responsively address racial trauma and racial battle fatigue in addition to providing equitable treatment with a culturally responsive approach for Black students. All school counselors must have this paradigm to engage all students. Therefore, a paradigm shift or decolonization of thinking must occur in order for counselors to be advocates — allies, accomplices, and co-conspirators — for Black students like Mason.

Einstein is reported to have stated: The world we live in is a product of our thinking. We cannot change things until we change our thinking. Accordingly, the first step for decolonizing is to change dispositions. School counselors must believe that every student deserves the right to a quality education and to have their needs met. In order for this to occur, counselors must challenge what they believe about students, especially those from urban, rural, and minoritized populations. Specifically, eradicating biases and beliefs that have traditionally served as barriers to authentic engagement with students has to be done with intention. For example, stereotypical beliefs and deficit thinking about Black males (e.g., dangerous, intellectually challenged, lazy, etc.) must be both challenged and eliminated. These biases have led to Black male low achievement and underachievement, not receiving the benefit of the doubt, inequitable suspensions, racism, and even death. Moreover, it is important that counselors empower students and families like the Johnsons to advocate for themselves, understand their rights in schools, and to be partners with them in achieving the goal of receiving an education that is engaging, equitable, and of quality.

Dr. Erik M. Hines

Dr. Erik M. Hines

Sample preventions, interventions to decolonize school counseling

Professionally, we have been troubled by the disproportionate focus on intervention rather than prevention among educators — teachers, counselors, and administrators. Consider this analogy: I (Ford) argue that it is better to prevent a fire so that you do not have to spend time intervening to put it out. In this spirit, we ask school counselors and other educators to devote more time to prevention. Even though the term ‘early intervention’ is used, it is still intervention rather than prevention.

Decolonizing preventions and interventions will take reflection/introspection on who the preventions and interventions were initially designed for and its effectiveness with various student populations. Interventions must not be culture blind. Moreover, school counselors must consider if these strategies and tools are both culturally responsive and sustaining so that students of various backgrounds not only feel included, but that the supports are relatable to their personal and school experiences. For example, counselors can use bibliotherapy (use of books to address academic and mental health issues) to work with Mason and other students. The literature and readings must be multicultural (Ford & Tyson, in press). Counselors must ensure that all books and readings are culturally relevant to students in the areas of race, gender, heritage, and community context. This intentional approach in decolonizing both prevention and intervention shows the thoughtfulness of a counselor recognizing how unique each student is and their proactive strategy of creating an ethos of inclusiveness.

When decolonizing school counseling, it is also essential to reflect and consider the degree to which one’s preferred counseling theories and approaches meet the needs and styles of minoritized students. There is a merger of traditional counseling with Black culture documented by A. Wade Boykin’s Afro-centric cultural styles. Specifically, Black students who are vervistic (movement oriented, high levels of energy, demonstrative) are likely to prefer Gestalt Theory because strategies are often tactile and kinesthetic. Students for whom oral tradition is strong may prefer Rogerian strategies where counselors are intentional about building trust, and being keen listeners who are non-judgmental. These humanitarian approaches place students like Mason at the center of strategies.

Decolonizing preparation and training

In a recent Diverse article, Dr. Kelly A. Rodgers and I (Ford) urged educators to get out of the ivory tower and into the communities of students of color. Doing so will strengthen one’s cultural awareness and competence — dispositions, knowledge, and skills, respectively.

Decolonizing higher education preparation means focusing on the importance of culture in all aspects of counseling students of color, as noted above. There is a good volume of work on multicultural counseling, which ends any excuse to be ill-informed, culture blind, or culturally assaultive. Faculty can find curricular and instructional resources for sections of courses and entire courses for degrees, licensures, and credentials to prepare future and current professionals to be culturally competent with their Black students and other students of color.

Decolonizing education, school counseling included, consists of at least five interconnected areas, according to Ford in multiple publications and presentations:

1. PHILOSOPHY - As mentioned above, dispositions are fundamental for decolonization to occur, and for being receptive to self-reflection in the process of change. The more resistance to change, the more effort is needed by faculty and presenters. We urge faculty and supervisors/administrators to be persistent, and to model decolonization in words and actions;

2. LEARNING/COUNSELING ENVIRONMENT - Our expectations of Mason and other students of color directly influence the counseling environment, building trust, and selecting strategies. When students view the environment as welcoming, non-judgmental, and culturally responsive, school counselors will have productive sessions, as well as productivity in every stage of counseling;

3. CURRICULUM - The content and focus of counseling sessions must be anti-racist and culturally responsive to be useful for minoritized students. Bibliotherapy, cinematherapy, art and music therapy, for example, must consist of authentic and high-quality multicultural literature, movies/videos, art, and music that appeals to and resonates with students.

4. INSTRUCTION - The counseling methods and strategies adopted must be made with students’ cultural characteristics and styles at the forefront of decisions for implementing the counseling process. Suggestions were noted earlier.

5. ASSESSMENT - Evaluation is ongoing in the counseling process. Instruments and measures must be bias free or culturally neutral. Instruments must be selected with care and normed on Black students, as explained by Ford, et al. We must be ever mindful of APA’s long overdue apology to people of color about historical and ongoing biased instruments.

We end this call for action as we started it, by applying Einstein’s thoughtful message to school counselors: the counseling process we have created is a product of our thinking. We cannot change things until we change our thinking. Mason and other Black students are waiting. No time is better than now to decolonize our minds. Then, our hearts and actions will follow.

Dr. Donna Y. Ford is Distinguished Professor of Education and Human Ecology in the Department of Educational Studies in the College of Education and Human Ecology at The Ohio State University.

Dr. Erik M. Hines is a Professor in the Counseling Program in the Division of Child, Family, and Community Engagement within the College of Education and Human Development at George Mason University.