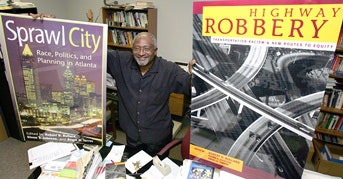

Dr. Robert Bullard

Dr. Robert BullardDuring Dr. Robert Bullard’s first stint at Texas Southern University, researching assorted urban issues while also teaching, he linked where some people live with their comparative lack of household finances, and from there, parsed how those dual forces factor into what gets dumped in their proverbial backyards.

Landfills, garbage incinerators, industrial plants and other polluters are more likely to be situated in areas populated by poor, politically powerless people, Bullard concluded, as he began backing up what he knew was true anecdotally with empirical evidence.

He also concluded that those living near landfills, toxic smokestacks and such also tend, disproportionately, to travel outside of their neighborhoods for well-stocked supermarkets. They confront shortages of affordable, habitable housing and insufficient means of transportation. They are less likely to get hired by major employers — including industrial polluters operating in their communities — who pay wages that reasonably sustain a family.

“Those questions go to the heart of equity and justice,” says Bullard, who, after departing TSU in 1987, returned last year as dean of its Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs.

From the school of public affairs, Bullard aims to pump more minority graduates into environmental policy-making and monitoring, an arena still largely dominated by Whites. Likewise, he says, TSU also is striving to push more professionals into spheres intersecting with the environmental arena.

“The environmental lens brings it all together,” he adds. “There’s a reason why we have childhood obesity and asthma epidemics in certain populations. There are reasons for high unemployment and high dropout rates. … We need to unravel and disentangle the institutional factors that make communities sick, that lower property values. That’s an overlay I’ve tried to bring to this field, trying to set a framework for people to understand how all of this is connected.”

The return of pioneering Bullard — dubbed “father of the environmental justice movement” — to a programmatically expanding TSU has been a much-welcomed personnel move, says Dr. John Rudley, TSU’s president.

“His research is cutting-edge,” Rudley says of Bullard. “And his service to the public is evident in his ground-breaking environmental and sustainability studies. The panels upon which he serves, sharing best practices regarding environmental policies that respect all people, allow him to be a voice [for] the voiceless and underserved communities in America and around the world.”

Following his more than decade-long tenure at TSU — he also was a visiting professor at Houston’s Rice University during that period — Bullard also landed positions at the University of Tennessee and the University of California’s Berkeley, Los Angeles and Riverside campuses.

In the academy and public sphere, he continues to cite urban quality-of-life issues, environmental parity, land use, transportation equity, racial disparities in health and wellness and everyday community interests.

His TSU students share some of Bullard’s motivations, and they are both challenged by his stated mission and honored by his presence on an HBCU campus.

“In these times, as in years past, raising a ruckus is essential,” Bullard has said. There has been much progress in the environmental arena, whose mainly White leaders used to dismiss notions that race played a role in, say, who lived too close to a polluting industrial plant. They also wrongly presumed that Black people also were oblivious to environmental concerns. “There was a time when the Sierra Club, in the South, wouldn’t even let Black people sign up for membership,” Bullard says.

He reminds others of that fact and continues to push for more inclusion in an environmental movement still navigating the minefield of race, class and geography. He pushes for more change as Houston itself keeps morphing. Houston, Bullard adds, now is the nation’s fourth-largest city. Its Black population is larger than Atlanta’s. The Latino population has now doubled that of Blacks, although in 1987, the Black population was double that of Hispanics.

“We need to do a better job of attracting Latino students,” Bullard says. “We want to be able to recruit more international students, to recruit more students across the spectrum, particularly with emphasis on the environmental and sustainability fields. … That’s the charge I’ve been given, that branding emphasis, that focus on doing more research, [winning] more grants and more notoriety in terms of our policy work.”

He wants TSU squarely in the midst of whatever is the upcoming progress on the environment and related matters. He is glad to still be in the fray.

“What I’ve tried to do over these years is work in a way that defines the environment as very holistic,” Bullard says, “framed in terms of where we live, work, play, learn, as well as in terms of the physical and natural world — which means we don’t leave much of anything out of this whole discussion.”