Taylor Branch is starting an online course on Dr. King as part of his mission to bring civil rights to the foreground of higher education.

Taylor Branch is starting an online course on Dr. King as part of his mission to bring civil rights to the foreground of higher education.Civil rights historian and award-winning author Taylor Branch is on a mission to make the Civil Rights Movement more prominent in higher education—and he’s teaching a new MOOC on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to do it.

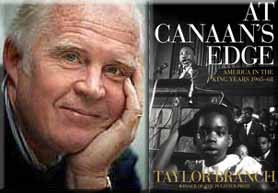

“I’m hoping the Internet technology will open (courses) up at a cheaper cost for students from all over the place to have access to this history,” said Branch, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the newly-released “The King Years: Historic Moments in the Civil Rights Movement.”

The 190-page book—a “guided distillation” of Branch’s longer trilogy on the King years—is the basis of a new course Branch is teaching this semester at the University of Baltimore through a small-group honors seminar that is also being offered on a trial basis as a MOOC, or Massive Open Online Course.

Though MOOCs have been all the rage in higher education as of late, the rationale behind the new MLK MOOC, if you will, involves more than just using the power of technology to deliver education more broadly.

“This is an experiment for me,” Branch, who said he only recently learned about MOOCs, told Diverse during a recent interview. “What we’re hoping to test is the possibility that students online would be able to take the course for credit and, if not for credit, for some fee that could make it economically sustainable.”

He added: “I want as diverse a group as possible.”

Branch—who taught a similar course at his alma mater, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, although not as a MOOC—said he was surprised to learn then that the university didn’t have a basic course on the Civil Rights Movement.

“They had all kinds of courses on identity politics and that sort of thing, but not a basic course on the Civil Rights era, and that’s also true at many other colleges, I was surprised to find,” Branch said.

Branch is hoping to change that through the new MLK MOOC he is teaching at the University of Baltimore. In addition to teaching the honors students, who pay for the course and take it in the regular class setting, Branch is also reaching dozens who have decided to audit the course as a MOOC. They don’t have to pay, but, in exchange for their participation, the university asked for auditors from “diverse fields, backgrounds and locations, including participants from outside the United States, to provide feedback on transforming the captured experience into a possible future Massively Open Online Course (MOOC),” according to a statement from the University of Baltimore.

A Diverse reporter accessed the MLK MOOC online forum and found an assortment of college and university instructors or administrators who said they had signed up for the course out of their love for history, or curiosity about MOOCs, or both.

For instance, Monica Wildes, an adjunct professor of sociology who is pursuing her Ed.D in Higher Education Leadership and Change at Fielding University, said her purpose for signing up was “examining the efficacy of providing MOOCs as an option for learning.”

“I believe that this is the next dimension of not just higher education, but all forms of education and I am grateful to be a part of this audit group,” Wildes wrote in the online forum for the course-takers.

“It has already given me ideas on how to improve my own course by bringing professionals of various backgrounds into my classroom virtually via Skype and Ustream to enhance the learning experience,” she added.

Though the Diverse reporter has yet to attend a class session online, the reporter still got a glimpse of what Branch is teaching during a recent panel discussion titled “Race, History, and Obama’s Second Term,” held at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C., in conjunction with the issuance of the January/February edition of Washington Monthly, which has a cover story of the same name.

At the event, Branch recounted how when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Washington, D.C., in 1961 for his first private meeting with President Kennedy, he harbored hopes that the president would end segregation by executive order with the stroke of a pen.

But King was dismayed when administration staffers prevailed upon him the need to get rid of “subversives” on his own staff before the Kennedy administration, which did not want to alienate its political base in the Democrat-controlled and segregationist South, would even begin to discuss any sort of alliance.

“This is a very complex dance, more about control than anything else,” Branch said. “Because if you admit you have somebody that you need to get rid of that is subversive, then you’ve almost conceded control over your agenda and your associates to the other party.”

King ultimately got to visit President Kennedy at the White House, but it was “not on the books,” Branch said, and First Lady Jackie Kennedy attended. The subtle message to Dr. King was: This meeting is a social visit, not a political one. But King managed to broach the topic anyway as the two men passed by the Lincoln Bedroom and King called attention to the Emancipation Proclamation.

King tactfully suggested that Kennedy sign a similar proclamation that would end segregation. Despite the administration’s professed interest in “hearing more,” King never got a response after he delivered a draft he had worked on for half a year in 1962 leading up to the 100-year anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. Branch said the non-response led King to realize that there would be “no easy way out” and that greater sacrifice was needed to end segregation in the United States.

Branch said he hoped that since 2013 is the 50-year anniversary of a series of monumental Civil Rights era events—from the historic March on Washington of 1963 to the assassination of JFK—that the anniversaries would stimulate more honest dialogue about the role of race and politics in America.

Branch noted that President Barack Obama has discussed race “less than any other president in the past 50 years”—in part because of backlash that occurs anytime he delves into a racial issue, such as the fatal shooting of Black Florida teenager Trayvon Martin by a neighborhood patrolman who thought he was suspicious.

“That’s no accident because we’re still limited from the upside of our own history,” Branch said of Obama’s reluctance to speak on matters of race.