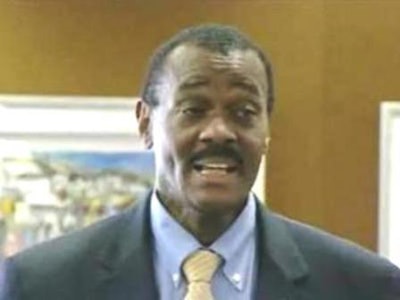

Dr. Allen L. Sessoms was ousted as president of the University of the District of Columbia in 2012.

Dr. Allen L. Sessoms was ousted as president of the University of the District of Columbia in 2012.SAN DIEGO, Calif.—Shortly after he signed on to lead the University of the District of Columbia in 2008, Dr. Allen L. Sessoms knew that his college presidency was doomed.

Faced with a meager budget and not enough money to pay the university’s light bill, he said that city leaders gave him a clear and uncompromising ultimatum: “Fix the college or tell them how to close it.”

Unable to secure support from the current or former mayor of Washington, D.C., the possibility that Sessoms would enjoy a long presidency at the only public institution in the nation’s capital grew dimmer by the day.

Since he was fired in 2012, Sessoms has largely remained quiet, taking a position as a senior fellow at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, and working as a vice president for The Hollins Group, an executive recruiting company that is spearheading the search for a new president of the NAACP.

But yesterday, he broke his silence, appearing on a panel at the American Council of Education conference, titled “Presidential Near-Death Experiences,” where Sessoms said that the land grant university founded in 1851 wasn’t serious about making dramatic changes during his time as president.

During the session, which was moderated by Dr. Stephen Joel Trachtenberg, president emeritus of The George Washington University, Sessoms and former West Virginia University president Michael Garrison recounted their experiences as ex-university presidents at public universities.

“I learned that a president at a public university can’t succeed if the political class don’t want you to succeed,” said Sessoms, who was previously the president of Delaware State University and Queens College in New York City before he was hired to lead UDC. “A president can’t fix an institution without the majority of people at the institution wanting to fix things.”

In Sessom’s case, not only did he regularly clash with the former and current mayor, but he was also forced to do governance with a board of trustees that decreased from 15 to five during his tenure.

A trained physicist and former diplomat, Sessoms was hired to reinvigorate the historically Black college and university, but soon after he arrived, he faced widespread criticism, first when he reorganized the college, which grants two-year and four-year degrees, and then when he raised tuition and admission standards.

There were also allegations about the possible misuse of funds, including tens of thousands of dollars spent on hotels and first-class flights in 2010 to Boston and Egypt. Sessoms denies the allegations and said that he was cleared by an independent audit.

“I don’t miss the job,” said Sessoms, who added that he has been nominated for other presidencies but would be more selective if he ever decided to become a president again.

“I’m not going to take a job where I have to engage in shoot outs every day,” he said, adding that the burdens that college presidents now face often make them the scapegoats for public scrutiny.

Trachtenberg understands the logic. For nearly 20 years, he served as president of The George Washington University and wrote Presidencies Derailed: Why University Leaders Fail and How to Prevent It, which was released last year.

“People are shooting at our regiment,” said Trachtenberg, who noted that college presidents are blamed for things that are often beyond their control.

At one time, many academics yearned to be a college president, Trachtenberg said. But that is not necessarily true anymore.

“People are running away,” he said. “Provosts don’t want to be presidents.”

Jamal Watson can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on twitter @jamalericwatson