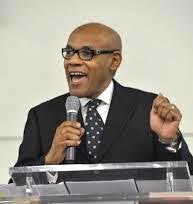

Dr. Jeffrey Stewart, chair of the Black Studies Department at UC Santa Barbara, said he believes that having greater diversity on campus doesn’t hurt African-American students, but it doesn’t necessarily help them, either.

Dr. Jeffrey Stewart, chair of the Black Studies Department at UC Santa Barbara, said he believes that having greater diversity on campus doesn’t hurt African-American students, but it doesn’t necessarily help them, either.Harvard University hit a milestone in 1969, enrolling its first class containing more than 100 African-Americans, according to a 1975 report by The Harvard Crimson. Such a milestone was not celebrated by all, however, as a number of media outlets published pieces attacking the students and Harvard’s affirmative action policies. One such article appeared in a September 1973 issue of the New York Times Magazine and was written by Dr. Martin Kilson, Harvard’s first fully-tenured Black professor. In the article, titled “The Black Experience at Harvard,” Kilson observed how many Black undergraduates regularly sat together at the same tables during meals, and accused the students of self-segregation and intellectual withdrawal.

Kilson essentially attacked the Black students for rejecting racial integration. In response, one Black student activist, Bill Fletcher, noted that it was easy to photograph Black students eating together but asked, “How come the Times didn’t run photos of rich White students getting drunk at the elite WASP final clubs?” Within a year of that class graduating, a research study, conducted by sociologist Don Barfield of the Harvard Efficacy Project on behalf of Harvard College, revealed that Black students actually had a wider range of social interactions than Whites.

One of the profound ironies of that controversy is that both Kilson and his opponents still argued in terms of Black and White. At today’s multicultural universities, those demographics are ancient history. On some campuses, both Black and White students are a minority. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, between 1999 and 2010, the number of Black students earning bachelor’s degrees increased by 53 percent, Hispanics by 87 percent, Asians by 51 percent and Whites by 27 percent. For master’s degrees, the ethnic change is even greater: Blacks, 109 percent; Hispanics, 125 percent; Asians, 81 percent; and Whites, 39 percent.

And despite years of attacks on affirmative action, the Supreme Court preserved an important mechanism for bringing “minority” students to campus, but shifted the argument from affirmative action as restorative justice to diversity as a legitimate societal need. Also, the movement toward educational diversity has not only changed who is on campus, but what can be taught, even in the Deep South. For example, Louisiana State University offers degrees in women’s and gender studies, and students can earn a degree from the University of Alabama in jazz studies. In 2012, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette started offering a minor in LGBT studies.

A new reality

In discussing the importance of diversity, Dr. Claude Steele, the recently appointed provost of UC Berkeley, declares that, “I don’t mean just any kind of diversity. I mean the kinds of diversity that are probably most critical to redressing social and economic equality concerns in society. That certainly would include racial diversity, but it also would include class and income diversity.”

Steele continues: “I also sometimes mean it with a slight edge toward intellectual diversity, because I’m a strong believer that that’s a central element of excellence.”

Dr. Jeffrey Stewart, chair of the Black Studies Department at UC Santa Barbara, said he believes that having greater diversity doesn’t hurt African-American students, but it doesn’t necessarily help them, either. “Often, they end up feeling isolated on campuses that may now have many students who are not White, but still have very few Black Americans.”

Stewart also points out that, while Black studies departments were established as a direct challenge to traditional academia, “A generalized diversity does not automatically bring a critical attitude toward the race, gender, and class hierarchies of Western civilization, or toward the historical role the university has played in furthering that discrimination.”

Dr. Clarence Lusane, a professor of political science and international relations at American University, cautions against pitting African-American students, faculty and staff against other communities and groups that have also historically been excluded from opportunities in higher education. He feels that each group’s history should be addressed on its own merits and appropriate remedies developed from that assessment.

“It is also important to note that African-Americans also cross other racial, class and cultural boundaries,” Lusane says.

Affirmative action redux?

One unintended consequence of California’s Proposition 209 was that, by ending race-based affirmative action for African-Americans, it also substantially reduced the number of White students on campus, particularly working-class men. Across the UC system in 2013, 36 percent of freshmen were Asian, 28.1 percent were White, 27.6 percent were Latino and 4.2 percent were Black. And, given California’s changing demographics, tight finances and fierce competition from well-heeled, academically qualified foreign students, the fight over who can attend state colleges will probably escalate. Indeed, in January 2014, the California State Senate passed bill SCA5, which would repeal 209’s ban on race, ethnicity and gender as a consideration for public college admission.

According to the Associated Press, Republican State Senator Joel Anderson of Alpine, Calif., acknowledged the problem of shrinking access to state colleges, but argued that, rather than approve SCA5, the state should limit the enrollment of foreign students to create more room for California residents. “It doesn’t create more space in our colleges and universities,” Anderson said of SCA5. “It just rearranges the chairs on the Titanic.”

What SCA5 may mean for California, or the national debate over affirmative action, remains unclear. However, Dr. Sam Johnson, chair of the psychology department at Baruch College, observes that even legislative and court decisions that strengthen affirmative action will most likely only impact students aspiring to attend the most competitive institutions, though the effect on faculty or staff hiring would probably be more widespread.

“We shouldn’t forget that a decent percentage of universities, and many community colleges, admit almost everyone who applies,” says Johnson. “For the largest number of African-American and Hispanic students across the country, the biggest question isn’t, ‘Can I get in?’ but, ‘Can I afford to go?’”