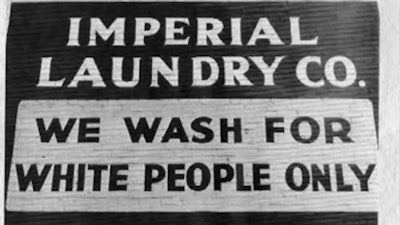

But a new research paper says the fact that African-American students are more likely than white students to enroll and make good grades at University of North Carolina institutions can be “explained entirely” by a remaining legacy of the Jim Crow era—the state’s operation of several HBCUs.

“Our research raises a policy dilemma regarding the strategies employed to address inequality,” states the paper, titled “Public Universities, Equal Opportunity, and the Legacy of Jim Crow: Evidence from North Carolina.”

“To the extent that opportunities for disadvantaged students depend on less selective, poorly-resourced institutions originally designed to serve one race, any expansion of these opportunities may well reduce disparities in educational attainment at the cost of perpetuating both segregation by race and inequality in the quality of education,” the paper states. “But the current stratification of students across campuses might be desirable, if students learn more when taught alongside others who share their educational aspirations, needs, and backgrounds.”

The authors—public policy professors Charles T. Clotfelter and Helen F. Ladd, of Duke University, and Jacob L. Vigdor, of the University of Washington—concede that “fully addressing this dilemma is well beyond the scope of this paper.”

The authors consider it “deeply ironic” that Black UNC students—by virtue of their attendance at the state’s five HBCUs—on average have a “remarkably more racially isolated experience in college than they had in 8th grade.”

“At the same time that the state’s HBCUs serve to raise the college enrollment rates of African–American students, the Jim Crow legacy embodied in these institutions intensifies racial isolation for black college students,” the paper states. “As a result, black students who enroll in the UNC system are likely to attend college classes with markedly higher percentages of black students than they had encountered in 8th grade.”

The paper notes that, whereas the average black UNC matriculant had been in an eighth grade where 34 percent of their peers were also black, in college that average was “dramatically higher” at 65 percent, the paper notes.

But the characterization of higher concentrations of black students at HBCUs as a “racially isolated experience” drew criticism in some quarters.

“I don’t think HBCUs are isolating at all,” said Marybeth Gasman, a higher education professor and director at the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions at the University of Pennsylvania.

“They are empowering,” Gasman said.

Gasman also said the dilemma raised in the paper is nothing new.

“However, what should really happen is all of North Carolina’s institutions should be funded equitably,” Gasman said. “This means that the institutions with students that need the most help and support should get the most money. Currently we give the most money to students that need it the least.”

The research paper—released recently through the National Bureau of Economic Research, or NBER—deals with a range of stratification issues related to the socioeconomic status of North Carolina’s students and the selectivity of the colleges they attend.

For instance, the paper notes that children of college graduates enjoy higher rates of entry into UNC and its most selective institutions than the children of less educated parents—a pattern the paper says is “by no means unique to North Carolina.”

“Although children of college-educated parents made up only 29 percent of the 8th graders in 2004, they constituted 57 percent of the subset that would eventually enroll in the UNC system,” the paper states. “And, on average, these children of college graduates ended up on campuses where 62 percent of their fellow students also had college-educated parents.”

The paper also notes that the UNC system serves a disproportionate share of black students with moderate-to-low eighth-grade test scores.

“These students are disproportionately represented at HBCUs; white students with comparably modest 8th grade test scores are much less likely to be found on any UNC system campus,” the paper notes.

The paper says the UNC system’s HBCUs play a “pivotal role in enrolling African-American students.”

“Relative to white students with similar parent education and test scores, black students have higher rates of enrollment largely because of the five HBCUs operated by the state,” the paper states.

African-American students are also between 1 and 2 percentage points more likely to attain a 3.0 GPA or declare a STEM major relative to white students with similar background characteristics, the paper states. However, they are “slightly less likely to attain a high GPA at UNC-Chapel Hill relative to white students with similar background characteristics.”

In terms of graduation rates, the paper states that the black-white gap holds at 5 to 6 percentage points—even after controlling for test scores and parent education.

“Relative to white students with comparable backgrounds, African-American students enjoy better access to the UNC system—and access matters,” the paper states. “But once on campus, black students have less success than whites in earning a degree.”

On the other hand, the paper notes that—holding eighth-grade scores constant—African-American students in North Carolina are more likely than whites to earn a four-year degree within four years of finishing high school from a UNC institution.

“This advantage can be attributed entirely to a higher propensity to matriculate in the first place,” the paper states. “This matriculation advantage more than offsets the black deficit in conditional graduation rates.”

The authors concede the paper is not meant to estimate the “treatment effect” of attendance at an HBCU and recommends other ways to probe the effects of matriculating at an HBCU.

Jamaal Abdul-Alim can be reached at dcwriter360@yahoo.com. Or follow him on Twitter @dcwriter360.