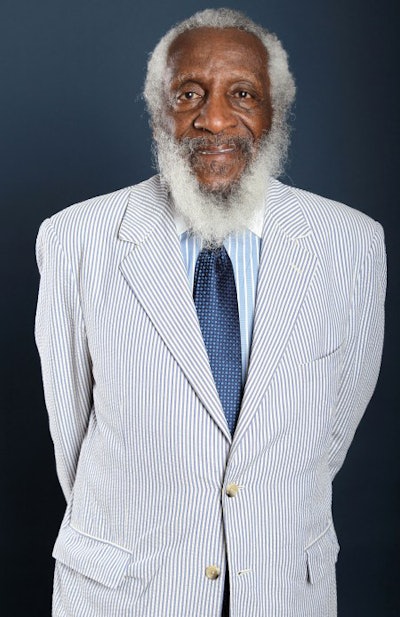

Comedian and activist Dick Gregory who committed his life to social justice through both satire and sincerity, died on Saturday at the age of 84.

Gregory was born in St. Louis in 1932 as the second of six children. After graduating from high school, he attended Southern Illinois University on a track scholarship. Halfway through his education, he was drafted into the Army in 1954. In the military environment, he was recognized and reprimanded for his inclinations towards humor.

Comedian Dick Gregory was a civil rights activist, comedian and frequent lecturer on college campuses across the nation.

Comedian Dick Gregory was a civil rights activist, comedian and frequent lecturer on college campuses across the nation.During his service, Gregory won a talent show with a comedy routine. After the Army, he left school to pursue stand-up comedy in Chicago. Gregory’s comedy career took off in early 1961 after he filled in for Irwin Corey at Playboy’s night club in Chicago. He was subsequently signed by Hugh Hefner for three more weeks.

The indirectness of the social critiques in his jokes allowed him to appeal to a larger, white audience. This made Gregory’s charisma on the stage all the more subversive. In one of his most well-known jokes, he recalls eating at a restaurant in the South where a white waitress said, “We don’t serve colored people here.” Gregory responded, “That’s all right, I don’t eat colored people. Bring me a whole fried chicken.”

“Dick Gregory was unafraid to analyze and describe the world as he encountered it, and through that, as a Black man in America engaging the world, he was able to articulate what so many of us have felt,” said Dr. Greg Carr, chair of Afro-American Studies at Howard University and a friend of Gregory.

Carr said that Gregory’s jokes came from a place of love, fearlessness, and genius. Carr said that Gregory never crossed words with anyone and that he would speak to his audiences and his students until the point of exhaustion.

“Gregory was a perpetual student. He was always reading,” Carr said. “His intellectual capacity was honed to precision with a lifetime of deep study.”

In 1962, Gregory traveled to Mississippi to rally for black voting rights. A year later, he was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama. His work for the Civil Rights Movement gradually replaced his stand-up comedy. In the 1960s he fasted to raise awareness about everything from the Vietnam War to police violence. His weight once dropped to a mere 95 pounds.

“Even the best activists get tired and weary,” said Carr. “But Dick Gregory seemed to have this ability to receive the energy he was giving.”

In the decades following the Civil Rights movement, Gregory committed himself to a healthy lifestyle. He gave up meat, drinking, and smoking. In 1973, he stopped working on premises that served alcohol. In 1984, he started a Health Enterprises Inc., a company that sold diet foods.

In the past decades, Gregory continued to be active in social justice. In 2000, he protested against police violence and education inequity throughout the country. After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, he fasted to raise awareness for Haitians suffering.

In 2016, he voiced his opinion in a debate at Seattle University in which students protested their dean’s inclusion of his provocatively titled memoir Nigger in the university’s curriculum. In an essay published in Inside Higher Ed, Gregory urged the students to read his book and engage in the difficult yet important discussions. He also directed the students’ attentions to what he saw as more urgent matters like police brutality, sexual assaults on campus, and the high cost of education. He ended the piece by offering to provide the books for free.

He wrote, “Classrooms must also provide space to discuss how books from previous generations may be problematic yet remain very much connected to modern-day issues.”

That wisdom was imparted by the same man who decades ago aroused laughter with this joke: “Segregation is not all bad. Have you ever heard of a collision where the people in the back of the bus got hurt?”

For Carr, this duality speaks to the legacy of Gregory. He said that the media and the public should not “trap people like Dick Gregory in time.” Although his contributions to the civil rights and Black Power movements were immense, Carr said that Gregory’s legacy is much more universal.

“His commitment to a common humanity was not abstract. It was literal,” said Carr. “It’s going to be very difficult to grieve Dick Gregory,” Carr continued. “Even as we talk about him he’s going to be there.”

Gregory is survived by his wife and ten children. He was scheduled to perform at the Howard Theatre in Washington D.C. in November.

Joseph Hong can be reached at [email protected]