WASHINGTON — Diversity practitioners from schools across the country have gathered this week at the 12th annual meeting of the National Association of Diversity Officers In Higher Education (NADOHE) to learn the best practices to foster diversity, equity and inclusion on their college campuses.

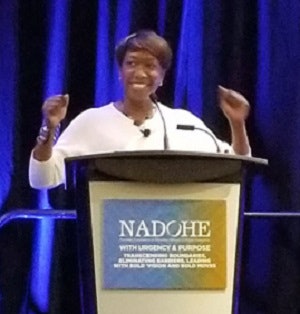

Joy Reid of MSNBC speaking at NADOHE annual meeting Thursday.

Joy Reid of MSNBC speaking at NADOHE annual meeting Thursday.In sessions and workshops throughout the conference — themed “With Urgency and Purpose: Transcending Boundaries, Eliminating Barriers, Leading with Bold Vision and Bold Moves” — NADOHE leaders and other institutional diversity officials shared strategies on how to hold candid conversations on campus, how to engage in diversity work without an official “chief diversity officer” title and how to achieve an environment of inclusive excellence.

“It’s a taxing and tolling kind of work” that diversity officers do, said Dr. Archie W. Ervin, president of NADOHE and vice president for institute diversity at Georgia Institute of Technology. “But that’s important, because the work must continue.”

MSNBC journalist and commentator Joy Reid opened the conference with a keynote highlighting the common challenges and tensions students of color face on various campuses. Challenges include being in a hostile environment or living and learning in buildings named after controversial figures such as Woodrow Wilson. Another challenge students face is not having institutional support, which could lead to wider disparities in degree-completion rates across racial groups.

“When you rank the United States against other developed nations, we score relatively low on everything from math and science ability to engineering degrees and STEM, and really every sort of sign of modernity and advancement,” Reid said. “Much of that gap has to do with the ongoing racial gap internally. If you caught students of color up with White students, you would actually close the United States’ gap with the rest of the world.”

During her remarks, Reid also recalled that her experience at Harvard University was “extremely jarring” because White students openly questioned Black students’ intelligence and presence at the school, and because there was a lack of Black faculty whom students could look to for support.

“We’re still fighting this battle for diversity and inclusion in everything, but particularly in higher education,” she said.

Invoking a U.S program to help Western European economies after World War II, Reid said: “We need an education Marshall Plan, and that Marshall Plan has to start with students of color.”

Reid encouraged institutional diversity practitioners to begin their work with honest conversations about race on campus.

“We’re so gentle with this conversation about race that we never get to it,” she added. “It’s unavoidable. It is the most important thing that we have to get out and that we have to get to the root of.”

In a later session titled “Implicit Bias and Microaggressions: Eliminating Barriers and Obstacles in Pursuit of Inclusive Excellence,” Dr. Gretchel L. Hathaway and Jason Benitez from Union College explained that officials can create safe spaces and engage students, faculty and staff in challenging conversations regarding race and diversity by recognizing their own implicit biases.

“Everybody has a bias,” said Hathaway, dean of diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer at Union. “Own it. Put a flashlight on yourself. Take a look at what are your issues.”

Benitez, Union’s associate dean of diversity and inclusion and director of multicultural affairs, added that while officials must come to terms with their implicit biases and how they can unconsciously influence objective decisions, they should also realize that biases are reinforced in students through parents, education, literature and especially media.

Biases are “learned, but [they] can be unlearned,” Hathaway added.

The diversity officials’ suggestions for breaking habits of prejudice and avoiding microaggressions for staff and students include taking the Implicit Association Test (IAT), exploring the “awkwardness and discomfort” of dialogue around different people’s experiences and interacting with people from groups considered “other.”

“Uncomfortable does not mean unsafe,” Benitez said. “It’s our charge as higher education practitioners to create opportunities for students to have inter-group interactions. Exposure is really what’s going to help.”

Hathaway added that asking questions such as “What is it that you’re uncomfortable about?” or “Where were you coming from when you said that?” – or sharing a simple story – can create a campus climate of respect for all. “You have to do the work to get to this space.”

In “Doing the Work Without the Title: Advancing the Inclusive Excellence Effort as a Non-Chief Diversity Officer,” Dr. Keith R. Barnes shared that it is important for all higher education leaders to embody and demonstrate some level of understanding of equity, diversity and inclusion whether or not they hold an official diversity job.

“We have to stop operating in our privilege when talking about diversity work,” said Barnes, executive director of diversity, equity and inclusion at Pikes Peak Community College in Colorado Springs. “Even people who have the official roles are struggling to some degree.”

Barnes suggested that institutional leaders first define diversity and prioritize it in strategic plans. Second, he said, inviting an external consultant to conduct a diversity and inclusion audit – and then taking advantage of the opportunity to share that audit’s findings during program reviews, the accreditation process, climate surveys or campus crises – can be helpful for ensuring the campus gets “right about diversity.”

Referencing pioneers in diversity practices such as C.C. Poindexter at Cornell University, Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan at Radcliff College and Mary McLeod Bethune and Lucy Craft Laney at the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute, Barnes said it takes a collaborative effort among departmental units, institutional organizations and community partners to build a case for diversity on campus.

In some cases where the subject of diversity falls within an academic discipline, working with departments such as sociology, African-American studies or others can be beneficial, he said.

Other strategies for faculty and administrators to better engage in diversity work included lobbying for involvement in campus strategic planning processes and key campus committees; becoming familiar with CDO books, scholarly research and best practices in the field and identifying a culturally competent senior-level official who is committed to diversity.

However, Barnes warned practitioners not to get trapped into solely relying on uncommitted administrators who may come from a diverse population. Diversity practitioners should understand the budget process and leverage the cost of diversity efforts by collaborating with other campus units when possible, he noted. He added that working closely with Institutional effectiveness and research offices to create disaggregate data can be useful for assessing outcomes of diversity efforts, which could result in more funding.

Efforts to achieve inclusive excellence will succeed or fail depending on the level of commitment to equity, diversity and inclusion, Barnes contended

“This is hard work,” he said. “Don’t give up the fight because that’s exactly what people want you to do. CDO position or not, you need to have the will to change.”

Tiffany Pennamon can be reached at [email protected]. You can follow her on Twitter @tiffanypennamon.