Celebrity medical expert Dr. Ian K. Smith is taking a turn in his career and promoting a new mystery he’s written based on his experience as one of a few Black members of an Ivy League secret society.

Smith’s new book The Ancient Nine is loosely based on his experiences as an undergraduate at Harvard University in the late 1980s and early 1990s and as a member of Delphic, one of the school’s secret “final” clubs. The experience affected Smith’s life so much that he decided to write about it, he said in an interview with Diverse.

The Ancient Nine was released mid-September.

“This book is a thriller because it’s based on the secrets that are buried within these clubs,” says Smith, 49. “It’s also a coming-of-age novel in which a young African-American kid from the other side of the tracks” experiences one of these clubs that in the past have mostly been closed to people of color.

“I think, first of all the book is fun – it takes you behind the doors of this extremely rare secret society,” Smith says. “But I also think, in a way it’s also a social commentary of what has happened and what is going on. I think that people will and the observations … to be relevant today.”

College secret societies have been around since the 1700s and have included Kennedys, Bushes and Rockefellers as members, their history dating back centuries and their traditions drawing in history. Groups like Skull and Bones at Yale, the Sphinx Society at Dartmouth, the Ivy Club at Princeton and Delphic at Harvard were traditionally open only to wealthy, White males, not on paper but most certainly in practice. Their existence was wrapped around secret traditions and ceremonies practiced at mansion-like headquarters, with stories that are reminiscent of the Illuminati. A rumor has floated around that members of Skull and Bones dug up the corpse of their founder.

But as times changed, so did these organizations, with a push from campuses starting in the 1960s to add women and people of color.

In 1971, a student columnist at Yale complained that a “Black militant” had been inducted into Skull and Bones, The Washington Post reports. By 1991, women were allowed into that organization. One of the people who spearheaded that change was Austan Goolsbee, who would later become an adviser to President Obama.

Harvard has been in the news the last year for limiting the campus activities in which members of secret societies can take part. The university did not respond to a request to discuss the changes. Effective with the class of 2021, the institution bars members of single-sex final clubs as well as Greek organizations from holding school leadership posts, serving as captains on varsity athletic teams, or receiving an endorsement from Harvard College for fellowships.

Smith says he understands why Harvard is pushing for change, although he believes the methods may not be constitutional. Whatever the case, Smith does believe that the actions by the school can make for a great opportunity.

“This is a great time to talk about it because as a country we’re dealing with these gender and race issues,” says Smith.

The Chicago-based physician most known for VH1’s “Celebrity Fit Club” reality show grew up in a working class community in Danbury, Connecticut. He and his twin brother, Dana, were raised by a single mother. Smith said he studied hard, went to church and learned values from his mother and maternal grandfather, who was from the South.

He decided to become a doctor one day when he was 9 years old while sprawled across his grandfather’s bed reading an issue of Ebony magazine. “I remember reading an article about the dearth of neurosurgeons,” Smith says.

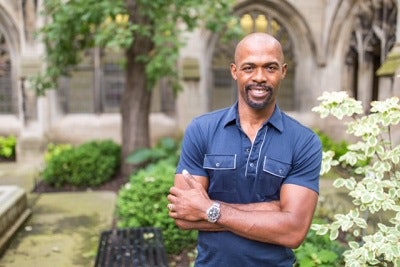

Dr. Ian K. Smith

Dr. Ian K. SmithIt was almost a fluke he said that he wound up at Harvard’s campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts, outside of Boston. He and his twin worked hard and earned good grades in high school. Smith knew Harvard was a good school, but he had no idea about the global reputation.

“We had no plan, no knowledge of how these schools operate,” Smith says of himself and his family. “It was almost dumb luck that I just had the qualifications. We were taught at home to always strive for excellence in everything.”

He adds: “As a kid, I was completely underwhelmed by the idea that it was Harvard. All I knew was that it was one of the best schools in the country and I got in and I was going to make the most of it.”

When he arrived as a freshman, he thought his life would be consumed with playing basketball and studying. Back home, his mother was working three jobs so he and his brother could get through it all.

“It was the first time that I was interacting with kids my age who had outrageously vast resources, legacy parents who inherited fortunes, people whose parents were head of the FCC and governors and Fortune 500 companies,” he says. “The beauty of being raised in a small town is that I was completely unfazed by it. I just looked at them as being different.”

The indifference continued one day when Smith found a nondescript invitation to a cocktail party slipped under the door of his dorm room. He ignored it until one day when he was in the locker room for basketball practice and he heard some classmates talking about getting “punched.”

After listening for a bit, Smith came to realize that getting punched was like being invited to apply for membership or Greek rush week for Harvard’s secret social clubs, called final clubs. Smith realized he was being invited to this process.

“I had no idea what a cocktail party was,” Smith says. “I picked out the best coat and tie I had” and went, he said.

The celebrity physician was accepted into Delphic, the same group that boasts the Aga Khan, actor Matt Damon, John and Ted Kennedy, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Teddy Roosevelt and T.S. Eliot. He was one of only two young Black men accepted that year, and it was a move that would change the course of his life.

At Harvard, final club headquarters are virtual mansions around campus, he says. “The clubs are very formal,” he adds. “It’s really like a mini country club – servants, staff, dining quarters inside these clubhouses, ballrooms with formal dinners, cigars and champagne. It’s very old school.”

While taking part in Delphic gatherings at Harvard, Smith was never treated differently – as far as he knew – because of his color. But he was intrigued by a photo on the Delphic wall of a Black member in the 1970s. The then-young man had an afro and his eyes beckoned to Smith, who felt a kinship with him. Smith in fact tried to track him down, without success.

“I always wanted to hear his story,” says Smith.

The celebrity doctor knew that he was walking a path traced by few Black people so he kept notes on his experiences all the time. The lead character in The Ancient Nine, a Black student from Chicago named Spencer Collins, is loosely based on Smith’s life.

Like Collins, Smith became intrigued by this new world and its secrets. He was particularly drawn to stories about two important historical texts held at Harvard under lock and key. One is the last remaining book from John Harvard’s collection that survived time and a 1764 library fire. These books figure into the story that he’s crafted.

But while The Ancient Nine is all about intrigue and questions, Delphic for Smith has primarily meant a great networking opportunity, Smith says. His participation in activities allowed him to see how people with money and power operate. And he now has a network that he meets for a formal meal every year in New York City.

“If I want to look in a club directory at someone who’s a partner at a law firm, that’s something that is open to me,” Smith says. “I think it’s one of those things where so many people don’t know about these clubs and the students don’t want to be a part (all the time), but I think that there is an inherent advantage … and other organizations that do the same thing.”

Smith believes his book is a fun trip through a space that few have experienced.

“I think that this is the first time that anyone has written about these clubs like this,” he says. “No one has really pulled the curtain back on the secrecy of these clubs. This is the first time that this has been happening.”

This article will appear in the November 29, 2018 edition of Diverse.