For Dr. Ronald A. Crutcher, president of the University of Richmond, higher education leadership is like performing in a chamber music group. In an orchestra, the conductor leads, telling the musicians how loud or soft, fast or slow, to play.

But in chamber music, the musicians play off each other.

Crutcher recently announced that he’s preparing to take the ultimate step back, retiring from the presidency before July 1, 2022 and returning to his role as a professor of music.

From a young age, Crutcher knew he wanted to go into academia. His first cello teacher, who taught him when he was 15 years old, worked as a professor at Miami University. He looked up to her as a role model and always imagined leading a life like hers, playing in a string quartet and teaching university students.

And that’s what he did. He was the first cellist to receive the doctor of musical arts degree from Yale University, debuting at Carnegie Hall in March 1985. As a graduate student, he received a Fulbright Fellowship, a Ford Foundation Doctoral Fellowship and a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. A graduate of Miami University, he also received honorary degrees from Wheaton College, Colgate University and Muhlenberg College.

He didn’t know he wanted to be an administrator until he was asked to serve as interim associate vice chancellor for academic affairs for undergraduate instruction.

“I liked the fact that every day I had different problems to solve,” he says.

Later on, a mentor at the University of Texas at Austin — where Crutcher directed the School of Music — told him it was obvious that Crutcher should become a university president. He’d never considered it, but once that “seed” had been planted, it clicked.

The importance of mentoring

A theme in Crutcher’s career path has been the presence of mentors, whether it was fellow academics or his father, who told him to start investing for his retirement during his first academic job at Wittenberg University. At age 73, that advice is paying off, he laughed.

Crutcher’s advice to young scholars is to cultivate mentors as much as possible, because in academia, they’re going to need it.

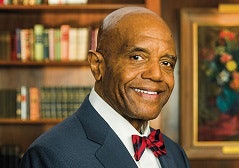

Dr. Ronald A. Crutcher

Dr. Ronald A. Crutcher“What I would say to young faculty members is that you have to realize, like it or not, universities, and particularly departments, are very political, just as much as government or business or the nonprofit sector,” he says. “You need to not only know the formal agenda but the informal agenda as well. And the only way you can know that is from mentors or colleagues.”

He says that the rewards of reaching out to a potential mentor far outweigh the risks. In his “entire life,” a colleague has never responded negatively to a request for advice.

“All you have to do is ask,” he adds, and it’s particularly helpful in the promotion and tenure process.

Crutcher also advised early-career scholars to be open about wanting to pursue leadership roles, if that’s, in fact, what they want. His advancement didn’t come out of “thin air,” he says. “Let people know if this is something that you’re interested in.”

Looking back on his career, Crutcher compared trying to pick his most proud accomplishment to trying to choose his favorite child. He’s proud of his work at the University of Richmond, especially in the area of diversity, equity and inclusion.

Over the last five years, 36% of hires have been people of color or international scholars. The university has a member of each search committee whose job it is to ensure that the committee is looking at a diverse applicant pool.

In terms of student diversity, he partly credits growing numbers to the school’s partnerships with local high school programs, which help the university identify high-achieving, low-income and minority students.

But “representational diversity is only the first step,” he says.

He also praised the school’s “distributive leadership model,” which disperses the responsibility for diversity work to leaders throughout the school, based on the idea that “no single leader alone can bring about cultural change.” He also pointed to the university’s first virtual summit on equity this fall and an ongoing inclusive pedagogy program. Meanwhile, there’s a three-year-old, weekly intersections discussion group focused on race and racism, started by one of the university vice presidents.

“Our goal is leading us towards becoming a strong intercultural community in which all of our members have the capacity to interact with each other in honest, direct ways across racial, across cultural, across social, across ideological divides,” he says.

Until Crutcher’s impending retirement from the presidency, he will continue to help the university respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, drawing on his breadth of experience. While the virus may be an unprecedented challenge, he’s weathered crises as a higher education administrator before, like 9/11 and the economic downturn in 2008.

“One of the advantages to having been in a senior-level role for almost 30 years — either as a provost or as a president — is you see a lot,” he says. “One of the things I learned is the critical importance of having a strong and collaborative team around me. Fortunately, I have that here. I tell folks who work with me constantly that they make it possible for me to sleep well at night.”

University of Richmond’s response to COVID-19

This year, the University of Richmond brought students back to campus for a condensed fall semester without fall break. In bringing back in-person classes, it also invested $10 million in campus resources and facilities related to COVID-19, including testing, contact tracing, teaching technology and modular units for quarantine spaces.

Until there’s a vaccine, “we’re going to have to learn how to live safely and healthfully with the virus,” Crutcher says. “That’s the perspective I have taken. Some people haven’t liked me saying that quite frankly, but I think that’s the reality.”

He thinks that the pandemic will change the university — not it’s mission as a close-knit, residential liberal arts college, but the ways in which it uses technology. In spring, when the university was forced to pivot entirely online, he found that a lot of his meetings, which would normally require travel, could be done virtually. He and his colleagues are also talking about how to use technology in the classroom going forward, using it to deliver more content to students so faculty can spend more time focused on fostering critical thinking about the content.

His question is, “How can we use technology at small residential liberal arts colleges to free up our faculty to do what they already do well, which is engage with our students?”

Two years from now, Crutcher hopes to be on a year-long sabbatical in Berlin, Germany with his wife. Afterward, he’ll return to the faculty at the University of Richmond, teaching a leadership course each semester and likely a first-year seminar in leadership or African American music.

But even across the globe, “we’ll always be a tireless advocate for the university and its faculty, staff and students,” he says of himself and his wife. “We’ve drunk the water.”

This article originally appeared in the October 29, 2020 edition of Diverse. You can find it here.