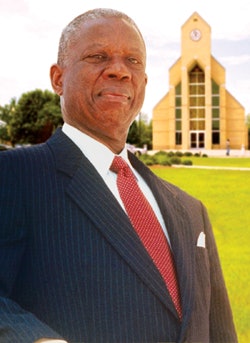

Dr. Luns C. Richardson has the distinct privilege of being one of the nation’s longest-serving college presidents.

And among presidents of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), the ordained Baptist preacher has outlasted his contemporaries, taking the longevity mantle from Dr. Norman Francis, who retired in 2015 after leading Xavier University in New Orleans for 46 years.

Richardson, who has been at the helm of Morris College for 43 years as its ninth college president, is now calling it quits, stepping down from the beloved HBCU that was founded in 1908 in Sumter, South Carolina, and has been affiliated with the Baptist Educational and Missionary Convention of the state ever since.

It’s the end of an era, particularly at a time when colleges are experiencing high turnover rates among their leaders.

Until 2014, Richardson had served for 56 years in a dual role as the pastor of Thankful Baptist Church, a small congregation, located in Bamberg, South Carolina.

Dr. Luns C. Richardson has retired from Morris College after more than four decades of service.

Dr. Luns C. Richardson has retired from Morris College after more than four decades of service.That role of preacher as college president would later be emulated by Dr. Floyd Flake, who presided over Wilberforce University while pastoring Allen A.M.E. Church in Queens, New York, and the Reverend Calvin O. Butts III, who pastors Harlem’s historic Abyssinian Baptist Church while leading the State University of New York at Old Westbury.

Despite Richardson’s busy schedule as a religious leader, those who know him say that he has a firm commitment to the college.

“His legacy could be defined by his reputation as a hands-on president,” says Dr. Marc C. David, who chaired the division of Religion and Humanities at Morris College from 2005 to 2013. “For example, Dr. Richardson insisted on interviewing every job applicant who visited the campus. During those interviews, he gave each candidate a history of the college, shared a personal story or two and tested the candidate’s knowledge of the college’s website. Afterward, he would wish the candidate the best and carry on with his day. If the applicant was hired, it was not uncommon for Dr. Richardson to extend his personal welcome.”

A native of Hartsville, South Carolina, Richardson came of age as the nation was in the midst of racial turmoil. As a youngster, he made the three-and-a-half-mile walk to a two-room grammar school that was racially segregated.

It was at home, however, that Richardson was taught certain traditions that stayed with him even after he became a college president.

“Saying grace before meals and reciting a Bible verse before the evening supper was a family ritual,” says Richardson, who was affectionately known as “LC” during his youth.

As the country was immersed in World War II, Richardson graduated from Butler High School in 1945 as class valedictorian and then went on to earn his bachelor’s degree from Benedict College. Later, he earned graduate degrees from Teachers College at Columbia University and pursued additional studies at South Carolina State University, Rutgers University and the University of Tennessee.

Chaplain and teacher, Richardson also served as a high school principal before moving into higher education. He later worked at Benedict College, serving for 16 months as acting president, and was the executive vice president at Voorhees College in Denmark, South Carolina.

By the time he had settled in as president of Morris College in 1974, Richardson was eager to turn the school around but had no idea that his presidency would eventually stretch across four decades.

“I thought I’d be here for about five years,” he says, adding that he stayed longer because he was determined to make some substantial changes, including ensuring that the liberal arts college became accredited. “We achieved our initial accreditation in December 1978, one year ahead of schedule,” he says.

Since then, Richardson has presided over the construction of 17 buildings and has been instrumental in growing the school’s endowment from $30,000 to more than $12 million.

He has also put Morris on the map, luring well-known political figures such as former Vice President Joe Biden to campus. James E. Clyburn, the powerful congressman from South Carolina, praised Richardson’s leadership.

“My family’s relationship with Morris College is very personal,” Clyburn says, adding that his mother graduated from the college when he was 12 years old. “My father studied theology at Morris in the early 1940s for three years but was not allowed to finish his studies because he had not graduated from high school.”

Having been born in 1897 in segregated South Carolina, Clyburn says that his father was never allowed to advance beyond the seventh grade.

“Though he was not allowed to graduate in 1945, as he should have, thanks to Dr. Richardson and the Board of Trustees, he was posthumously awarded his Bachelor of Theology degree 58 years later in 2003, a most proud moment for my family and for me.”

Beyond the brick and mortar, Richardson is best known for his commitment to academic excellence, according to observers.

“A physical plant means very little without accreditation and financial security. So Dr. Richardson’s legacy could be connected to Morris College’s solvency,” says David. “Many colleges have failed to meet accreditation or become defunct due to financial inadequacies, but Dr. Richardson pulled the college from near bankruptcy in the 1070s, and the college operated in the black throughout the rest of his tenure. Morris College also acquired accreditation under his leadership.”

In 2010, the university received its biggest private donation to date — a $10 million gift from an alumnus who hit the lottery.

“When I was aspiring to be a minister, I studied here at Morris College,” Reverend Solomon Jackson Jr. told Diverse in 2010 after he won the Powerball worth $260 million. “The experience helped mold me. I thank God for the training I received there.”

In honor of his work, Richardson has received more than 100 honors and awards and is the recipient of numerous honorary doctorates inlcuding from Benedict College, and Simmons Bible College in Louisville, Kentucky.

“It suffices to say, Dr. Luns C. Richardson is a giant of a man whose impact on the countless lives he touched, the City of Sumter, the state of South Carolina and indeed the entire nation will be felt throughout the ages,” says Clyburn.

This story also appears in the June 29, 2017 print edition of Diverse.