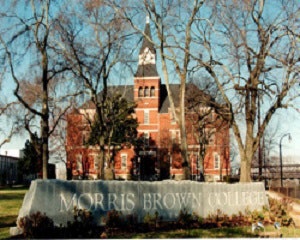

Morris Brown College has been up and down for the ‘final’ count so many times that many people have stopped counting.

Now, operating as a shadow of its historically rich self, the college was dealt another blow this month when the Georgia Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling that a land sale rooted in property sold by Morris Brown was illegal.

The sale, cleared by a federal bankruptcy judge as part of Morris Brown’s most recent emergence from federal bankruptcy, brought the decades-old institution more than $10 million to help pay down a $30-million tab of unpaid bills.

The 2012 sale of the land to Invest Atlanta, the City of Atlanta’s investment arm, was challenged in state court by neighboring Clark-Atlanta University, original owner of the property. Clark-Atlanta cited a clause in a 1940’s transaction between the two institutions that allowed Morris Brown use of the land for educational purposes.

At the time of the Morris Brown sale to the City of Atlanta, the property at issue had long gone unused by Morris Brown and belonged to Clark-Atlanta, the neighboring HBCU claimed in court. Lower courts in Georgia backed Clark-Atlanta’s claim, leading to the state supreme court ruling.

In a narrowly focused ruling on the legality of the land transaction, the high court was silent on what, if anything, to do about the funds the city paid Morris Brown.

The City of Atlanta press office did not return an inquiry about the court ruling. Clark-Atlanta did not comment on the fate of the money when Lance Dunnings, its general counsel, told the Atlanta news media last week the Georgia Supreme Court decision “should end the legal dispute concerning the ownership” of the property.

Morris Brown spokeswoman Adraine Jackson, speaking for Morris Brown President Dr. Stanley J. Pritchett Sr., said in a phone interview this weekend that Morris Brown was not party to the litigation in any respect and had no comment on the fate of the money it received in the transaction, all of which was disclosed in open court early on. She said the institution continues to focus on its future plan.

“We are laser-focused on accreditation,” said Jackson. She said the land sale revenue was a big help to the institution in whittling its debt list down to one creditor: the African Methodist Episcopal Church, a founder of the institution and a reliable financial standby over the decades when Morris Brown has struggled.

Jackson said Morris Brown understands an institution must be debt-free for at least three back-to-back years in order to apply for accreditation with the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC), the influential college standards peer group.

SASCOC endorsement of an institution is considered by the U.S. Department of Education before the agency gives an institution federal education funds to help pay a student’s tuition. Morris Brown, like most historically Black colleges and universities, was heavily dependent on federal student aid for its students.

Most of the school’s ongoing revenue needs are generated from alumni and innovative fundraising ideas that also help fund scholarships. Alumni run the Morris Brown parking lot near the Benz stadium in downtown Atlanta, for example. Parking revenue on game days brings needed funds to the school.

Noted radio personality Tom Joyner is scheduled to visit the school next month for graduation and plans to solicit funds to support its revival efforts.

While the Georgia Supreme Court left the million-dollar question unanswered by any party related to the land-sale question, the case does resonate across the HBCU landscape.

Many of the most financially fragile HBCU’s sit on acres of land near the center of many cities, property now eyeballed as gold mines for real estate and government land developers. Schools need money and time to figure out a long-term survival plan in a post-segregation higher education era when most institutions are open to all. Once restricted to Blacks during the days of racial segregation, HBCU’s and their surrounding neighborhoods are today fair game to the highest bidder.

Fisk University in Nashville sold part of its one-of-a-kind, priceless art collection, for example. Land around it is being gobbled up from Black homeowners at dramatically high prices, The same thing is happening all around the HBCU’s in Atlanta, around Howard University in Washington, D.C. and at Virginia Union University in Richmond.

Some deals have been more controversial than others. South Carolina State University, for example, sold several valuable tracts of land within the last decade in deals that resulted in successful fraud charges being brought against several former university trustees.

Whether public or private, the HBCU land is eyeballed favorably by developers, with land-use restrictions strictly governing the future of the property, as the Georgia case suggests.

Morris Brown, which had seen its enrollment rise to nearly 2,700 students in 2003, now claims approximately 55 students, Jackson said. While the institution has not been accredited by the SACSCOC accrediting council for more than a decade, it still enrolls students and gives some financial aid based on contributions from alumni and the AME Church, she said.

The institution’s 37-acre stretch of land, which once included historic Gaines Hall – a campus dormitory and one of the oldest structures in the city of Atlanta – has shrunk to approximately seven acres.

The institution still has its sights set on the goal of accreditation, despite losing financially fragile peers such as Knoxville College in Tennessee and Saint Paul’s College in Virginia, with others standing on the edge, said Jackson.

Morris Brown “wants to become what it used to be, and more,” Jackson said.

The long-term impact of the Georgia high court decision is still unfolding. The small print of the ruling is not yet known, including resolution of the money question, if it is raised, said several higher education fundraisers contacted around the nation. They stressed they knew no details of the court decision.

As for Morris Brown’s “laser focus,” goal, there was consensus on the school’s reading of what is required to apply with SACSCOC for accreditation with emphasis on several points.

“If your school has a chance to revive itself, it will be up to the board of make a plan,” said veteran higher education fundraising consultant Robert Poole. “The administration and board have to have a good, viable plan and get buy-in from trustees, alumni and the broader donor community,” said Poole, whose last stop before retirement was eight years as chief fundraiser for Meharry Medical College, a historic HBCU in Nashville. “You have to have a good plan.”

So far, Morris Brown is sticking to its plan with Pritchett, a former professional football player familiar with bumps in the road.