We are proud “firsts” – as we have been frequently in both our personal and professional lives. Each of us is in our second university presidency, and each time we’ve ascended to the executive role, we’ve been the first African-American leader to do so at our predominantly White institutions.

And as trailblazing and eternally grateful firsts, we both feel a special responsibility to help define a path for those who will come later and to identify and help develop those who show potential to follow in our footsteps.

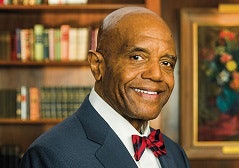

Dr. Ronald A. Crutcher

Dr. Ronald A. CrutcherAfter all, that’s what people did for us. Chris was mentored by another first – Dr. Muriel Howard (no relation) the first female president of the Association of State Colleges and Universities and first female president of Buffalo State College, State University of New York. Firsts take many forms. Ron is a classically trained musician who was the first cellist to receive the doctor of musical arts degree from Yale. One of Ron’s most influential mentors, Dr. Bryce Jordan, was the first musician to be president when he led Penn State; Dr. Jordan also was White.

It is not surprising that both of us have been mentored by people of all backgrounds. It’s hard to be a first if you haven’t been mentored by someone who has experience doing the job to which you aspire. According to the American Council on Education’s most recent American College President Study, the typical college and university president is a White man in his 60s, with people of color representing only 17 percent of college presidents. Women hold the top job at 30 percent of American colleges and universities.

But those numbers are slowly climbing, and as more women and people of color rise to leadership positions in higher education, we are increasingly mindful about the importance of mentorship in the academy and, particularly, for the office of the president. In the changing landscape of American higher education, we all have the responsibility to mentor. And that responsibility crosses all lines of difference.

Mentorship at the executive level in higher education serves a somewhat different purpose than in the world of business. Corporations place a premium on succession planning, so it is not unusual for a chief executive to choose their successor and mentor them in preparation for the top job. In higher education, when the people we mentor get their wings, they often fly off to other institutions and other opportunities.

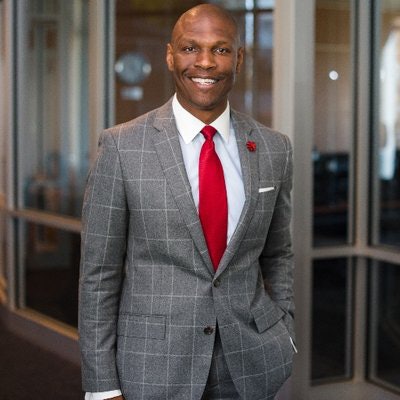

In the academy, therefore, we mentor not for the good of our individual institution, but for the good of higher education itself. Good leadership has never been more critical to higher education, given the myriad challenges our institutions now face, from sliding enrollments and increasing costs to heightened and varied forms of accountability. More and more routes now lead to the presidency: Chris had a career in the military and then the corporate world before starting a career in higher education. In fact, another nontraditional president, former Senator David Boren, started him on his path. Higher education needs to find and nurture good leaders no matter who or where they are.

Dr. Christopher B. Howard

Dr. Christopher B. HowardSo while mentoring a promising colleague might cost our own institutions a talented administrator or professor, we are making important contributions to the future of higher education. The reward to our own institutions comes in the reputation we earn for helping people of all backgrounds unlock their potential. Who wouldn’t want to work at a place like that, and for a president like that? Good mentoring is good marketing. It’s unsurprising that effective presidents, like Stephen Trachtenberg, president emeritus of George Washington University (and a valued colleague to us both), are effective mentors.

Good mentoring also calls for rigor and a degree of reflection on the part of the mentor and the mentee. We are both strategic in our approach to mentoring, and even assign mentees questions and readings in advance of our first conversation, including speeches we’ve given and op-eds we’ve written. All this ensures that there is meaningful investment on the part of both parties – that each have made a commitment. In crafting these assignments, we take time to reflect on our own journeys, and how we can continue to grow and improve in our own leadership.

Deliberative and effective mentorship is needed now more than ever. As the demographics of our nation evolve, so does the makeup of our students. We need to help prepare those future leaders who will reflect the racial and socioeconomic diversity of our changing society. Those of us who have gone before should be intentional in helping to identify and cultivate emerging talent.

What’s more, we are bracing for high turnover among college and university presidents. The Council of Independent Colleges reports that 49 percent of presidents at its member institutions expect to leave their current presidency within the next five years, as well as 65 percent of presidents at public doctoral institutions.

At a time when people are increasingly questioning the value of higher education, and where we are being scrutinized for our practices, policies and handling of crises, we all have a responsibility to leave the enterprise in a better condition than when we found it. We can’t do that without great leaders providing great mentorship to the next generation of promising university executives.

Dr. Ronald A. Crutcher is president of the University of Richmond and Dr. Christopher B. Howard is president of Robert Morris University.