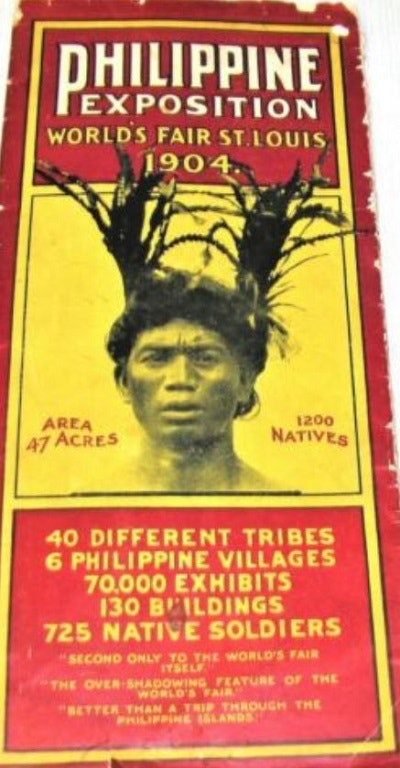

I wanted this on eBay – but got outbid.

It’s one of the original brochures of the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, where America first met the Filipinos in a setting that was essentially a human zoo, euphemistically called a “Filipino Exposition.”

An expo, what fun!?

During the week of Trump’s “go back” rhetoric, I was in Washington, D.C. doing my one-man show, “Emil Amok,” at the Capital Fringe. But the hot race talk of the day made me see a section of my show in a new way. It frames the “go back” story for every Filipino in America.

It begins with what happens after the Philippines was raped and pillaged in the Philippine-U.S. War —the rebellious post-mortem of the Spanish American War. The death toll of innocent civilians is estimated to be a million, just a fraction of the U.S. war dead.

White American show-biz entrepreneurs decided to put a happy face on that relative act of American genocide and help the government sell the U.S. colonization of the Philippines to the country and the world.

The expo featured 1,200 native Filipinos as if in a zoo: 40 different tribes, six Philippine villages, 70,000 exhibits, 725 Native soldiers.

The whole thing was billed as “second only to the world’s fair itself.”

It was also our “not-so-red-carpet” welcome to America, our new home and a harbinger of how Filipinos would be patronized and treated in this country, seen not as human beings equal to Whites but as America’s possessions.

Emil Guillermo

Emil GuillermoThey weren’t slaves, technically. Just America’s first colonized people. And they look so cute, don’t they? Real spear-chucking, loincloth-wearing genuine headhunters. And their families.

It’s a real example of a history no one talks about.

As I point out in my show, it’s America’s gateway to imperialism and explains the Filipino American experience. The 1904 World’s Fair coincided with the Chinese Exclusion Act process, which began in 1882, renewed in 1892 and then made Chinese immigration permanently illegal in 1902.

In part, the Filipinos were brought in to replace Chinese labor. It’s the reason the Filipino male to female ratio was 14-1. They were workers. Not intended to start families.

The labor purpose seemingly backfired because 30,000 Filipino men showed up, mostly in California by 1930.

They were colonized Americans. Nationals. They belonged. But it was also the Depression. Filipinos were taking jobs. And women.

Doors in Stockton had signs that said “Positively No Filipinos Allowed.” The Stockton Record editorialized that the Filipinos were not assimilable and shouldn’t be allowed to intermarry.

White nativists who feared the “peaceful penetration” by another race would move to exclude the Filipinos, just like they did with the Chinese.

As is often the case in any story, the best part was the sex parts.

Think White nationals fearing Filipinos stealing their White women and infecting the White race.

That’s how badly White men wanted Filipino men to go home.

In 1930s America, the so-called “Filipino Problem” was the burning immigration question. Politicians from Sacramento to D.C. were vocal. One of them was a member of the famed McClatchy media family.

And their ire was all directed toward Filipino men whom they saw as lusty effing rabbits.

There were no asylum seekers or caravans from Central America. No Mexican rapists, nor MS13 gang members. There were no people detained in cages.

In the 1930s, the big immigration issue involved that group of single Filipino men, mostly in California with the largest group in Stockton.

At the time, they were seen as not just threats to the sex part of White male privilege, but to the future ethnic purity of America.

In D.C., I explained my story to a Lyft driver, Freda, an older African-American woman driving me to my opening show.

I told her about the sexual jealousy of Whites toward Filipino men.

She looked at me and didn’t get it.

And then I said two words — Emmitt Till, a young African-American from Chicago, lynched in Mississippi after he was accused of whistling at a White woman.

Freda instantly understood my story.

Chronologically, Till’s murder came in 1955.

But the racist rage came from the same source that would fuel a “Go Home” story for every Filipino male in America in the 1930s.

My father was one of those single Filipino men at that time. He avoided Stockton and stayed in San Francisco because he knew that people were lynched in the Central Valley.

But his treatment in America was first framed by the Filipino human zoos at the 1904 World’s Fair.

I didn’t get the brochure on eBay. I was in the theater and got outbid.

But I don’t need it to tell his story and weave it into my own eastward journey that includes Harvard and NPR.

I brought my dad with me.

Few people, Asian Americans, Filipino Americans, Whites, have heard the full Filipino story. It’s forgotten history, which is understandable considering what a racist, sexist country America is.

Filipino head-hunters in loincloths on public display aren’t exactly a feel-good story.

It’s something America would rather forget. I won’t let them.

Emil Guillermo is a journalist and commentator. He writes for the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund. You can follow him on Twitter @emilamok