In the same month that the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial on the National Mall was officially dedicated, the NCAA board of directors passed measures that set higher academic standards and increased financial support for student-athletes. I am reminded that Dr. King wrote that “education must enable a man [and woman] to become more efficient, to achieve with increasing facility the legitimate goals of his life.” I commend the NCAA board of directors for its efforts to improve the educational experience of student-athletes.

Since the passing of the Student Right-to-Know Act, the relationship between academic performance and athletic participation in intercollegiate athletics has been under intense scrutiny. In an effort to keep college athletics grounded in the mission and values of higher education, the NCAA has demonstrated its interest in improving retention and graduation rates of Division I student-athletes by enacting, in 2003, the most comprehensive academic reform effort in years.

NCAA President Mark Emmert said, “Academic reform is working. Students are better prepared when they enter college, and they are staying on track to earn their degrees.” The latest graduation success rate of 82 percent set a new high for Division I student-athletes. Dr. Walter Harrison, chair of the NCAA Committee on Academic Performance and president of the University of Hartford, stressed that the latest classroom success is a result of the groundbreaking academic reform movement of the past decade.

The graduation success that we celebrate today came in spite of the necessary tension that exists between academic and athletic goals in higher education. Much has been reported about high-profile athletes associated with revenue-generating sports (e.g., men’s basketball and football) that have significantly lower graduation rates than other student-athletes.

This discrepancy in graduation rates continues to keep athletics in the news and is further exacerbated by issues like commercialization of intercollegiate athletics, the enormous economic cost of big-time athletics, and reports of academic corruption. Few issues in higher education might be debated more, or make more headlines in the media.

The current initial eligibility standards and percentages progress toward degree benchmarks have been a source of tension for student-athlete academic support units and college advisers. It has been reported that student-athletes are consistently admitted to colleges and universities with academic backgrounds significantly lower than their cohorts. As a consequence, these student-athletes sometimes have difficulty matriculating and require a lot of academic support to meet degree benchmarks.

Therefore, academic advising personnel have to play a key role in helping these students formulate strategies to fulfill their life and career goals.

Division I universities are mandated by the NCAA to provide student-athletes additional academic support—e.g., tutoring, mentoring, and academic counseling—to assist them in balancing academics and athletics. Hence, the potential for a role conflict between student-athlete academic support units and college advising units is pretty high. The tension is based on how each unit perceives its role when advising student-athletes.

A question that faces most academic support personnel is how the educational goals of the university blend with the NCAA athletic eligibility rules. The success of the recent graduation rates was achieved by the commitment that universities have made to provide a supportive environment for student-athletes to succeed in the classroom, community, and the field of competition. As Emmert said, “our work is not done.”

In theory, student-athletes should have a coherent experience working with an academic support team that communicates effectively and efficiently about course selection and degree progress benchmarks. The academic support team would consist of both college academic advisers and athletic academic counselors who, together, should have a comprehensive understanding of the curricula, course content, degree requirements and NCAA legislation.

Here are some suggestions to minimize the negative impact of the necessary tension that exists between academic and athletic goals. For instance, athletic academic support units should report to the chief academic authority office with a liaison relationship to the department of athletics. Also, athletic academic support units should have a seat at the tables of the appropriate leadership meetings of academic affairs, student-life, and athletics and serve on the appropriate committees that address student well-being. Furthermore, all academic advisers and counseling staff who work with student-athletes should be informed about the educational needs of student-athletes and should conduct regular meetings to create a comprehensive supportive environment.

In light of the new academic standards and student-athlete well-being measures being passed by the NCAA board of directors, it is imperative that colleges and universities take a proactive look at their current culture around supporting student-athletes in their efforts to balance their academic and athletic commitments. The suggestions listed above are meant to be catalysts for academic advising professionals and athletic departments to explore strategies to enhance their current efforts. As clearly demonstrated by the latest graduation rates, the commitment already exists on campuses. D

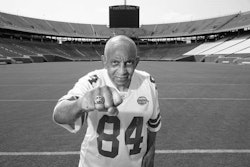

— Dr. David L. Graham is the assistant provost and associate athletics director for student athlete success at The Ohio State University.