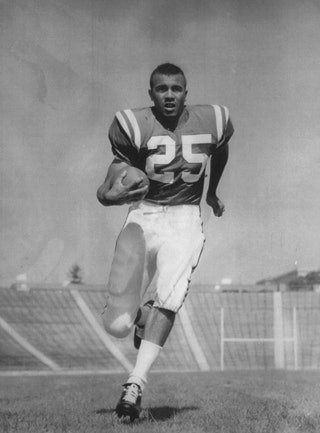

Darryl Hill

Darryl Hill

Another milepost in the struggle for equality didn’t garner the same attention that year, yet it carried as much social and cultural significance as anything else: Darryl Hill, a wide receiver for the University of Maryland, became the first African-American athlete to play in the Atlantic Coast Conference.

“College football in the South was god,” says Hill, who was honored at several events marking the 50th anniversary of the breakthrough. “The stadiums where those teams played were like temples where fans worshipped this god. When a Black man came on the field, it was like desecrating the temple, and they hated that.”

Hill, 69, was no stranger to being a pioneer when he enrolled at Maryland. The native Washingtonian previously was the first Black student to play football at D.C.’s famed Gonzaga High School and the first to play for the Naval Academy’s freshman team (where he caught passes from Roger Staubach).

But after Hill decided that military life wasn’t for him, Maryland assistant coach Lee Corso asked him about signing with the Terrapins.

“I asked Corso if he was aware what conference Maryland was in,” Hill says. “I thought he was joking. They were barely letting Blacks into the school, let alone play sports.”

Hill had mixed feelings about accepting the invitation, but not because he feared hostility. “I didn’t want to be under the microscope,” he says. “I didn’t mind being a groundbreaker, and I knew I could do the job. It was the effect it would have on my lifestyle; my reticence was based on my desire to party.”

Blazing a trail wasn’t much fun that year, especially the visits to South Carolina, Wake Forest and Clemson. Even the first home game was fraught with tension, as someone had called Hill’s dorm room and threatened to shoot him if he took the field. Maryland was a Yankee school in the eyes of its fellow ACC members, but there still were bars and restaurants nearby that didn’t serve Blacks.

During Hill’s first road game at South Carolina, he and his teammates had to fight their way off the field at halftime and after the final gun. In a game at Wake Forest, Hill was knocked unconscious, and White emergency medics refused to put the oxygen mask on his face (a teammate snatched it from them and gave it to Hill). A softer side of the South emerged before that game, when Wake Forest’s Brian Piccolo—of “Brian’s Song” fame—put an arm around Hill and silenced the jeering crowd.

Courtesy went a step further at Clemson, thanks to school president Robert C. Edwards. He invited Hill’s mother to watch from his private suite after she was denied entry to the stadium, per custom, and directed to a nearby dirt hill where other Blacks gathered for games. She spent the night at the Edwards’ home and remained lifelong friends with Edwards and his wife. Edwards integrated the stadium the following season.

“Opposing players were never the issue,” Hill says. “The fans were always the issue. There were times I could sense that opponents thought the people in the stands were being too nasty. They didn’t like it because it [took] away from the game. They were like, ‘Let’s play some football.’”

Hill went from the football field to a successful career as an entrepreneur. His name isn’t mentioned in the same breath with King, Evers and other notables, but he realizes the impact that sports pioneers had in countering negative stereotypes and improving race relations.

“When sports came all along, all of a sudden White America saw Jackie Robinson, Bill Russell, Jim Brown and Arthur Ashe sitting down and talking intelligently and radiating an image quite different than a lot of Americans had for Blacks,” Hill says. “Sports provided that opportunity, not because of the performance of Blacks on the field, but opportunities and exposure off the field. Sports played a key role in bringing the idea and image of equality from top to bottom for Blacks.”

Hill played a key role in the ACC, where today—a half-century later—nearly 60 percent of football players and 70 percent of basketball players are African-American.