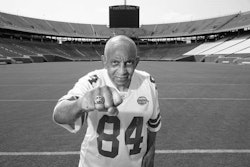

Oregon state Sen. Mark Hass says that “there is no path to the middle class” for those with a high school education as their only foundation.

Oregon state Sen. Mark Hass says that “there is no path to the middle class” for those with a high school education as their only foundation.

PORTLAND, Ore. ― Nothing sparks consumer demand like the word “free,” and politicians in some states have proposed the idea of providing that incentive to get young people to attend community college.

Amid worries that U.S. youth are losing a global skills race, supporters of a no-tuition policy see expanding access to community college as way to boost educational attainment so the emerging workforces in their states look good to employers.

Of course, such plans aren’t free for taxpayers, and legislators in Oregon and Tennessee are deciding whether free tuition regardless of family income is the best use of public money. A Mississippi bill passed the state House, but then failed in the Senate.

The debate comes in a midterm election year in which income inequality and the burdens of student debt are likely going to be significant issues.

“I think everybody agrees that with a high school education by itself, there is no path to the middle class,” says State Sen. Mark Hass, who is leading the no-tuition effort in Oregon. “There is only one path, and it leads to poverty. And poverty is very expensive.”

Hass says free community college and increasing the number of students who earn college credit while in high school are keys to addressing a “crisis” in education debt. Taxpayers will ultimately benefit, he says, because it’s cheaper to send someone to community college than to have him or her in the social safety net.

Research from the Oregon University System shows Oregonians with only a high school degree make less money than those with a degree and thus contribute fewer tax dollars. They are also more likely to use food stamps and less likely to do volunteer work.

A Gallup poll released in late February found 94 percent of Americans believe it’s somewhat or very important to have a degree beyond high school, yet only 23 percent of respondents say higher education is affordable to everyone who needs it.

As at four-year universities, the price of attending a community college has risen sharply because of reduced state support and higher costs for health care and other expenses. The average annual cost of tuition nationally is about $3,300, and books and fees add to the bill.

It’s cheaper than university, but expensive enough to dissuade someone who’s unsure whether to pursue higher education.

In Tennessee, Republican Gov. Bill Haslam wants to use lottery money to create a free community college program for high school graduates. It’s central to the Republican’s goal of making the state more attractive to potential employers by increasing the percentage of Tennesseans with a college degree to 55 percent by 2025 from 32 percent now.

If approved by the Legislature, the “Tennessee Promise” would provide a full ride for any high school graduate, at a cost of $34 million per year.

Meanwhile, Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber signed a bill March 11 ordering a state commission to examine whether free tuition is feasible. Among other things, the study will determine how much money the program will cost, whether the existing campus buildings can accommodate extra students and whether to limit free tuition to recent graduates.

The commission will also look at California, which offered no-cost community college until the mid-1980s, when a state fiscal crisis contributed to its demise.

The findings are due later this year and will help lawmakers decide whether to pursue the idea in 2015.

“What is exciting to us about the idea is that it signals that the state understands there needs to be significant reinvestment in community colleges in some way, shape or form,” says Mary Spilde, the president of Lane Community College in Eugene, Ore., where in-state students pay $93 per credit hour. In 1969-70, baby boomers paid $6 per credit hour ― about $37 in today’s money, adjusted for inflation.

Tennessee and Oregon are looking at the “last-dollar in” model, where the state picks up the tuition not covered by other forms of aid. Because students from poor families often get their tuition covered by Pell Grants and other programs, the state money would disproportionately help those from more comfortable backgrounds.

“If you’re paying for two years for everybody, then you’re paying for students whose families can afford to do it,” says Kay McClenney, director of the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas. “And is that your best use of dollars within the public interest?”

There are other concerns. Molly Corbett Broad, president of the American Council on Education, generally praised the bills, but says students are more likely to be successful if they have “skin in the game” and pay something toward their education.

Patricia Schechter, a Portland State University professor active in the faculty union, worries that students will be induced into taking the community college route ― “arguably against their interests” ― and about the effect on public universities, whose students won’t get a tuition break.

“We start competing for first-year students in a way that seems a little unfair if they can go somewhere for free,” she says. “It doesn’t address the creeping costs of higher ed. It just diverts them.”

Hass, the Oregon state senator, counters that the university presidents he’s spoken with, including Portland State’s, support the idea.

“There’s an old saying,” he says of the criticism, “You can marshal an army to preserve the status quo.”