The Southeastern Conference (SEC) ranks among the best in college football. It’s no secret that the league’s esteemed reputation was built with help from dominant Black athletes. The exploits of icons such as Herschel Walker at The University of Georgia, Bo Jackson at Auburn University and Reggie White at the University of Tennessee are well known. There was a time, though, when the Black presence on White college football teams in the Deep South was null and void.

All of that began to change in the mid-1960s. The University of Kentucky signed Nate Northington, who became the first African-American to play football in the SEC. In recognition of Northington’s place in history, CBS Sports has produced a documentary for Black History Month.

Forward Progress: The Integration of SEC Football will air on the network Feb. 16 at 8 p.m. The hour-long documentary examines the impact that Northington’s arrival had on Kentucky and the SEC as well as on the sports and cultural landscapes of America.

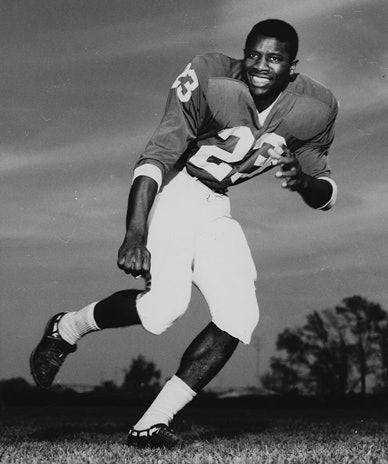

Nate Northington

Nate Northington

Among many college football fans, there’s a wrong assumption about integration in the SEC. The most common myth is that Alabama paved the way after taking a 42-21 beating from the University of Southern California during the 1970 season.

Northington reveals the true story about the league’s move to integrate in his autobiography Still Running, published in 2013. That same year, he received the inaugural Nathaniel Northington Groundbreaker in Athletics Award from the William Winter Institute of Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi.

“Folks look at the SEC today and see how much Black athletes have contributed to the league’s success,” says Northington. “What they don’t realize is that there are some forgotten aspects of how the conference has grown the way it has.”

Jack Ford, CBS News legal analyst and executive producer of Forward Progress, is familiar with Northington’s role in history. What surprised him was how many other knowledgeable college football fans had no idea that Kentucky was where it all started.

“Things have come full circle,” says Ford. “The SEC was the last conference to integrate and now it’s probably the most integrated league in college football. The documentary tells the story about a great moment in history that nobody knows about. It’s my hope that viewers will get a clear picture of what true heroism really is.”

Strategic plan

The move to achieve racial diversity wasn’t accomplished through a series of random acts. It was the byproduct of a strategic plan crafted by the state’s powers that be. As the northernmost state in the conference, Kentucky was viewed as the most likely to accommodate such a bold step. Then-Governor Edward Breathitt, former Governor Albert Chandler and then- Kentucky President John Oswald made it clear that the move to integrate athletics had their full backing.

Up until the mid-to-late 1960s, Black football players in the Deep South had limited options as far as playing for mainstream colleges. They could go north and play or go west and play. Because of the Jim Crow atmosphere, the fan bases at Southern White schools were often openly hostile toward Black players. So, Blacks were not recruited. To stay and play in the South meant that they would have to attend a predominantly Black school.

Kentucky was determined to sign Northington, an honor student and All- State running back from Louisville. When Breathitt invited the Northington family to join him for Sunday dinner in the governor’s mansion, there were no doubts about Kentucky’s intentions. After dinner, Breathitt presented his case to Northington, who, at that time, was thinking seriously about signing with Purdue University or the University of Louisville.

By choosing Kentucky, Northington would be close to home, which would give his family and friends plenty of opportunities to see him play. Not only that, but as a former Kentucky athlete, it would provide him with additional avenues for career opportunities around the state once his playing days were over.

Those were nice inducements, but it was the governor’s final selling point that altered Northington’s thinking. By opting for Kentucky, he would become the Jackie Robinson of SEC football. Northington realized that his signing would open doors for Black athletes in the future and, at the same time, help tear down one of the last vestiges of segregation in the Deep South. When Breathitt was through talking, he pulled out a scholarship offer sheet from his coat pocket. Northington didn’t hesitate to sign.

“As we talked, there was no denying that the governor was passionate about me signing and how much it would mean to integrate,” says Northington, a minister and regional director of property management with the Louisville Metropolitan Housing Authority. “The pitch was good. There was a lot of emphasis on how it would show that progress was being made.”

Unexpected events

Being a trailblazer didn’t turn out the way Northington thought it would. Not long after he signed, Kentucky added another Black athlete, Greg Page, an All-State defensive end from the eastern mountains of Kentucky. Northington and Page seemed destined to make history together, but it never happened.

During preseason practice in August 1967, Page injured his neck during a halfspeed defensive drill and was paralyzed from the nose down. Thirty-eight days later, Page died on the night before Kentucky’s home opener against the University of Mississippi.

Northington shattered the color line versus Ole Miss on Sept. 30, 1967. The sophomore safety played for about three minutes. On the third play from scrimmage, an Ole Miss running back broke free. Northington made the tackle, but his shoulder popped out of place and he was done for the day. Even though playing in the game was a history-shaping event, Northington had too much on his mind to celebrate the milestone moment. Page was his roommate and best friend. Coming to grips with this tragedy placed a heavy burden on Northington’s heart.

“I didn’t learn about Greg until the morning of the game,” Northington recalls. “It was devastating. My mind wasn’t focused on football at all. All I was doing was going through the motions. When I came out of the game with the shoulder injury, it was devastating all over again. I just wanted to be able to contribute to the team. I wanted to do that for Greg.”

In the following weeks, Northington struggled to cope with Page’s death. It didn’t help matters that a recurring shoulder injury severely limited Northington’s playing time. Now he was the only Black on the team, and he felt betrayed by the Kentucky coaches who made a solemn promise to recruit more Black players. Kentucky signed just two Black players in ’67: Wilbur Hackett and Houston Hogg.

To make matters worse, the coaches took away Northington’s meal card because he had missed a lot of classes during the time that Page was hospitalized. As a result, he would have to make his own eating arrangements.

That’s when Northington decided to leave Kentucky. Before his departure, he spoke to Hackett and Hogg. His message: stay and play. Northington closed out his college career as the star running back on the Western Kentucky team that won the Ohio Valley Conference title in 1970.

“Greg and I expected to finish together,” says Northington. “Dealing with his injury and his death was very difficult. All of a sudden, I’m all alone and there’s no one for me to talk to. I felt like I was isolated. As for Wilbur and Houston, I advised them to stay so that they would finish what Greg and I started.”

Hackett and Hogg heeded Northington’s advice and blazed some trails of their own. Both became the first African-Americans in a major sport to play their entire college careers at Kentucky. Hackett, a two-time All-SEC linebacker, made history as the first Black team captain in the conference.

“We wanted to leave, but Nate encouraged us to stay,” says Hackett. “Nate and Greg showed a lot of courage in coming to Kentucky to help bring about a change. But we never looked at ourselves as pioneers. We were in a struggle. There was all the name-calling with the N-word, the disrespect and death threats. But we stuck it out. We prayed a lot and there were a lot of people who prayed for us. It was God who got us through it all.

“I’m glad that CBS decided to tell this story. It’s long overdue.”

Hogg says he realizes that Northington faced a difficult situation and that his decision to transfer wasn’t an easy one. But given all that Northington had experienced, Hogg feels that, under the circumstances, it was the best move for Northington to make.

“Nate didn’t have anybody to lean on,” says Hogg, who played running back. “It was a very rough time for him. It was just best for him to get away from the situation he was in. Back then, it never crossed my mind about making history. I had two reasons for being at Kentucky: to get an education and play football.”

— Craig T. Greenlee is the author of November Ever After, a memoir about the 1970 Marshall football plane crash.