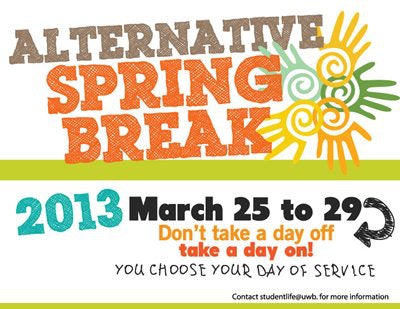

Posters like this one at the University of Washington, Bothell advertise service-oriented spring breaks, which are growing more popular among students.

Posters like this one at the University of Washington, Bothell advertise service-oriented spring breaks, which are growing more popular among students.INDIANAPOLIS — Last year, IUPUI student Cole Johnson found himself on spring break in Florida amid hordes of college partiers celebrating a week of bikinis and booze.

And he spent 168 hours not making a difference in anyone’s life.

“It was almost moving backward,” Johnson, 22, told The Indianapolis Star. “I didn’t see a point to it anymore.”

This week, Johnson is leading a group of students from Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis to work on a farm in Virginia. An “alternative” spring break program, the substance-free trip explores food production and sustainability.

Johnson is among a growing number of college students who are giving up the traditional go-wild spring break in favor of service learning trips. Indiana colleges say their alternative spring break programs are gaining momentum as students become more aware of social issues on a global scale.

“Sometimes, you have literally no idea what you’re going to get into,” said Johnson, a senior studying supply chain management. “That’s one of the beautiful things about the program. It teaches you to be adaptable and teaches you transferable skills.”

This month, degree-seeking Hoosiers will work with newly arrived immigrant families in Texas, a food bank in Washington, D.C., and Native American communities in Tennessee and New Mexico. They will build houses through Habitat for Humanity in Missouri, repair homes in the Appalachian Mountains and improve the quality of life for people with HIV/AIDS in Indianapolis.

In recent years, alternative break programs have responded to disasters such as Hurricane Katrina and damaging tornadoes in the Midwest and South.

Breakaway, a national alternative break network based in Atlanta, connects programs from 175 schools. Last year, it estimated its members gave more than 600,000 service hours.

So why would college students forsake vacations for service learning trips?

First of all, alternative breaks can be a lot cheaper.

Even with some of the international programs, several Indiana universities subsidize a significant amount. Schools estimate the all-inclusive trips cost about $1,500 to $3,000 per student—but at IUPUI, for example, the students’ portion comes out to just $100.

And civic engagement broadens what students learn in classrooms.

“When I’m in Bloomington, it’s hard for me to realize what social issues really impact our area,” said Indiana University sophomore Kristin Budzik, 20.

When she travels to Ecuador this week to work in the coastal forests, “I’m able to see it in a different light,” she said, “and how (social issues) are affecting our community here.”

The trip is through the Kelley Institute for Social Impact, which combines business with community service and global development.

Alternative breaks expose students to diverse situations. Sometimes, it’s a culture shock.

During a trip last year to Guatemala to build a daycare, Ivy Tech Community College-Bloomington students visited families living in one-room shacks with mud floors and no running water. Malnourished children didn’t have shoes and drank from the same river they used as a toilet, remembered Chelsea Rood-Emmick, the campus’s executive director of civic engagement.

When the group left the families, a student broke down into tears.

“You have students who knew that this would be poverty but didn’t realize how real it was going to be,” Rood-Emmick said.

Ivy Tech is returning to Guatemala this year; this time to help local farmers build a middle school.

“You don’t want the students to come back and have romantic views of poverty, or get these views of ‘Anything helps,’” Rood-Emmick said. “You have to think critically. How can we help people in a way that’s empowering? In a way that’s constructive, that helps people make differences in their own lives?”

The trips often seem to have a greater influence on changing students’ outlooks, more than changing the lives of the people they help. It can translate in little ways, like a student who becomes more conscious about recycling after an environmental-themed break.

It can translate in larger ways. One of Rood-Emmick’s students joined the Peace Corps. Another switched majors from English to social work.

And some keep at it. Taylor Pennell, 22, an IUPUI senior, has been on four alternative break trips.

“It gets us out of our comfort zone,” she said, “which is, what we’ve come to learn, where we grow the most.”

For her fifth trip, she is heading to Maryland to work in a domestic violence center.

The students reflect daily on what they have learned. What did you do? How do you feel?

Then: So what? Why does this matter?

“Now that we’ve had this experience,” Pennell said, “what are you going to do about it?”

Information from: The Indianapolis Star, http://www.indystar.com