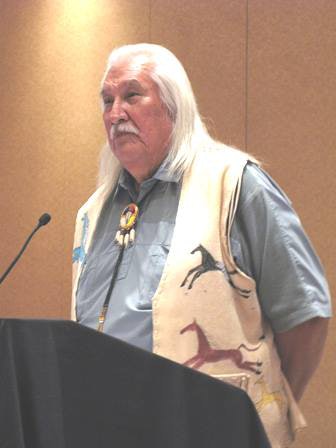

Lionel Bordeaux, president of Sinte Gleska University, speaks at the AIHEC annual conference.

Lionel Bordeaux, president of Sinte Gleska University, speaks at the AIHEC annual conference.SANTA FE, N.M. – The American Indian Higher Education Consortium proudly celebrated its 40th anniversary during a conference last week, but also had a sense of urgency about preparing for the future.

Teachers, administrators and students who attended AIHEC’s annual conference explored new ways to preserve their culture and languages, boost student retention and form international partnerships, among other efforts.

Tribal colleges must think globally, some speakers said. Students who study abroad would be better equipped for the future and the colleges could do research on an international level and raise their profile, they said.

Dr. Verna Fowler, president of the College of Menominee Nation in Keshena, Wis., said she originally wanted to let “20, 30 years” go by to build up the college before thinking about international education, but was pushed into it.

“Time waits for no one,” she said.

Fowler, whose school started an internationally recognized forest sustainability institute, urged her peers to look into collaborating with government agencies and other universities on international efforts.

She urged setting ground rules early on.

“Be strategic—make sure you both benefit,” Fowler said. “They [a partnering institution] may have 400 faculty members, but, if they can’t agree to that [the rules], don’t waste your time.”

AIHEC is pushing for an American Indian university that would contain law and medical schools. It is also working with the World Indigenous Higher Education Consortium to increase the number of indigenous people doing post-graduate work, among other initiatives.

Another workshop held at the conference touched on improving student retention, with some administrators saying the key is creating relationships with first-year students and giving them a firmer understanding of what their goals are and how college can help them.

Lanette Clark, financial aid director of Fort Peck Community College in Poplar, Mont., said school officials respond quickly if a student misses a couple of classes.

“I hate that the student is given a $500 scholarship and they’re out the door after a week or two,” she said. “We check on them.”

At Sitting Bull College in Fort Yates, N.D., a staff member might drive many miles to see what a student is up to, according to Lori Hach, who works with first-year students.

The school has tried a more structured, in-depth, hands-on approach with first-year students. They are required to meet with math and English instructors and learn about the importance of education, setting short and long-term goals, learning styles and time management.

Some participants said the tribal colleges must share among themselves experiences and ideas on retention because their situations are so different from those of other institutions.

Dr. Betsy Barefoot, an expert on first-year students, said those who get off track tend to be low income, poorly prepared academically, work more hours at jobs, are their families’ first generation to go to school and lead pressured lives that are filled with distractions.

In-depth orientation, summer “bridge” programs, learning while doing service in the community, pro-active advisers and one-on-one tutoring or coaching are some tools that have proved effective, Barefoot said.

Research shows students who are behind in the basics do better in mainstream classes than in separate tracks, said Barefoot, but need a lot of help in the meantime.

Participants also heard ways to keep tribal languages alive, which are in danger of disappearing along with the older generations.

The languages are now being learned in the classroom, not naturally, according to Inee Slaughter, executive director of the Indigenous Language Institute.

More people need to speak these tongues, and the tribal, state and federal levels all must be involved, she said, adding, “It takes a village to nurture a language.”

She suggested that language teachers cater to what students want to learn, and spread use of the languages in social media.

According to Lionel Bordeaux, president of Sinte Gleska University in Mission, S.D., it was a struggle to set up the AIHEC, which today includes 37 institutions that serve people in 15 states and Alberta, Canada. The college system initially started out with a handful of institutions, and ran into apathy and contempt among members of Congress during the early 1970s.

He shared some painful memories of trying to get lawmakers to sponsor legislation to recognize and fund the tribal colleges. “You’re good with your hands,” one from the Midwest told Bordeaux, referring to Indians in general. “Stick with the arts and crafts.” The man said Bordeaux’s people should concentrate on raising hogs and chickens.

Incensed, Bordeaux kept his cool, and eventually the lawmaker became a strong backer of the tribal colleges. Early supporters included the Congressional Black Caucus and the community colleges.

Early opponents even included a national tribal organization.

“Here we are, something so good, so innocent,” Bordeaux said, “yet there were people who were not as politically in tune as we were. We were facing opposition.”