When I teach the history of Mexican people at the University of Arizona, going back to the era of Spanish colonialism in the Americas, I teach two concepts that seem to be applicable to the United States of America today. One of them is called “primary process” and the other “principio.”

The first concept comes from Victor Turner’s 1974 book, Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors. He actually borrowed the concept from Sigmund Freud and applied it within a political context. Primary process is repressed energy that can no longer be contained and then explodes violently in a wild fury.

Amid this chaos, then what? That is where principio enters the picture.

Within the Mexican context, the leaders of this revolt, most of whom were not indigenous, called for a return to the way things were, prior to the arrival of Europeans to this continent. In this particular instance, they call for the restoration of “the Aztec empire.”

And whom they look to for inspiration is Cuauhtemoc, the last defender (speaker) who led the resistance against the Spanish invading forces. Enrique Florescano, in National Narratives in Mexico, describes this process as principio, a purported return to the roots or to a return to authenticity.

Both issues are much more complex, but it is the general idea of revolting and then returning to one’s original roots. Florescano also says that the same process occurred during the very violent Mexican Revolution, from 1910 to 1920.

This is why the current chaotic state of affairs in the United States is reminiscent of these two processes. Ever since the new president was sworn in, we appear to be in a constitutional crisis, especially with the signing of each new executive order.

The massive Women’s Marches around the country and world, the day after the inauguration, sent an unambiguous message to the White House. In addition, there have been many more controversial executive orders, including one that calls for the construction of a 2,000-mile wall.

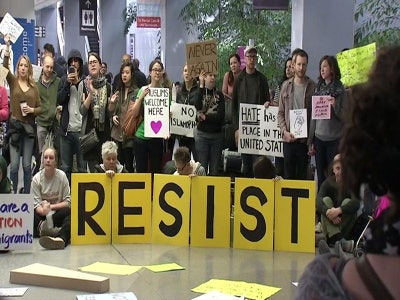

However, the executive order relative to the Muslim travel ban, affecting Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Syria, Sudan, and Yemen, is what appears to have tipped the scales. People are proclaiming, “This is Not Who We Are.” Opponents of the order, seemingly on both sides of the political aisle, are proclaiming that this violates the U.S. Constitution and that it is everything opposite of what the Statue of Liberty stands for.

This has triggered massive protests at airports nationwide, and at the same time, it is causing a lot of soul-searching among all sectors of society, including colleges and universities. These include my own, in which the president of the University of Arizona, Ann Weaver Hart, has proclaimed that she is not in support of the president’s policy, while also urging international students and scholars to postpone their travel.

Such statements and positions are being announced at other colleges and universities nationwide, including the 62 members of the Association of American Universities, which are urging the president to overturn the ban as quickly as possible.

Those spontaneous and massive protests across the country and worldwide are reminiscent of primary process. And the soul-searching and the assertions, that we have to uphold our authentic ideals, or return to them, is akin to principio. A massive uprising without principio is simply part of that volcanic explosion. However, when one proclaims a return, then it signals a philosophical discussion if not direction.

Thus, what could be a good thing has to be unpacked. For many of us, a return to the ideals of this country in fact is a nightmare. The Statute of Liberty was never for Red-Black, Brown or Asian peoples. The original ideals in this country included Providence and Manifest Destiny. Those ideals permitted genocide, land theft, conquest, and slavery. It also permitted legalized segregation, legalized discrimination and racial exclusion.

They have also permitted racial profiling to thrive in this country, which has resulted in the deaths of many thousands of people of color, just in the past few years, and the incarcerations of many millions also. It has also resulted in the mass incarceration of many Asians (Japanese in the 1940s) and massive and periodic deportations of Brown peoples throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

Perhaps in this spasmodic process and soul-searching, rather than a return to “our past ideals,” we should be thinking about humanity’s greatest ideals that do not include any of the above. It also should not include the concept of American exceptionalism, the idea that has permitted the United States to wage permanent worldwide war wherever it sees fit. If one examines this ideal/policy, it is not something that was created as a result of the attacks of 9/11, but it has existed for the majority of this nation’s history.

Therefore, what can be suggested is not so much a return, but rather the beginning of dialogues with ourselves, with politicians, the country, and the world itself. Indeed, we appear to have entered a new era … and that primary process has probably just begun.

Dr. Roberto Rodriguez is an associate professor in Mexican American studies at the University of Arizona.