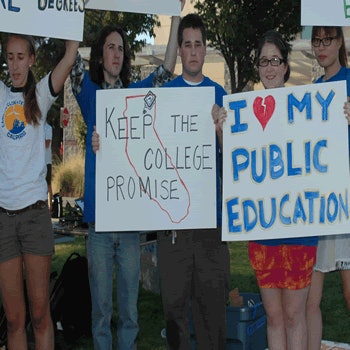

When San Francisco announced in February that it would make community college tuition free for all city residents, regardless of their income, it joined a multitude of cities and states that are doing something similar. According to the most recent count from the College Promise Campaign, an initiative tracking these numbers, nearly 200 states and localities have initiated “College Promise” programs.

A panel of three leaders in the college promise movement discussed the forces at work behind the initiation of promise programs and how states and cities are bankrolling these programs at a time when funding for higher education overall is on the decline at the Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education (NASPA) conference in San Antonio on Monday.

The concept of “free” tuition at the nation’s community colleges gained national attention under President Obama when he proposed a national America’s College Promise program during the 2016 State of the Union address. While a subsequent bill and efforts to develop a national framework did not gain traction, states and localities are moving ahead with programs of their own.

The argument for college promise programs is a straightforward one: by broadening access to postsecondary education for more students, who might otherwise perceive college as out of their reach, colleges will help increase participation in the economy.

“In the 1970s, you could get a great, middle-class job with just a high school diploma,” Dr. Joe May, chancellor of the Dallas County Community College District (DCCCD), said on Monday. “That’s all you needed.”

Today, that is not the case. Often, experts in higher education talk about the importance of advancing educational agendas to meet future workforce needs. The Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce estimates that, by 2020, 65 percent of jobs will require a postsecondary degree. Yet that future would appear to already be here in some parts of the country, May said.

According to a recent study of the 122,000 jobs that were created in the Dallas area in 2015-16, he said, 65 percent of those jobs required some form of postsecondary education — 32 percent require a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 33 percent require a certificate or an associate degree. In some areas, the proportion of jobs requiring some form of postsecondary education is closer to 72 percent.

“That’s why promise programs become so important,” May said. “We really have to think about how do we make postsecondary education accessible to everyone.”

To succeed over the long term, promise programs “should be sustainable,” said Dr. Martha Kanter, meaning that they “shouldn’t just redirect federal or state aid.”

Kanter is the former chancellor of the Foothill–De Anza Community College District in California, the former Under Secretary of Education under President Obama, and currently a prominent figure in the College Promise movement.

Having the support of elected officials is also critical, Kanter said, and has been integral in helping initiate many existing promise programs and has helped raise the idea in other areas. In New York, for instance, Gov. Andrew Cuomo recently proposed the ambitious Excelsior Scholarship program, which would make tuition free at SUNY and CUNY schools.

Although an elected official might prioritize a promise program and help it get off the ground, there is no guarantee that his or her successor would make the same commitment. “When [elected officials] go out, budgets change and priorities change,” Kanter said. That means promise programs need independent funding sources.

Current promise programs are currently funded through a range of sources, such as college operating budgets, college foundations, K-12 school district budgets, and state and federal allocations. Most have multiple funding sources.

Dr. Karen Gross, an educational consultant and author who is the former president of Southern Vermont College and a former senior policy advisor to the Department of Education, struck a cautionary note at the panel, saying that, while she believes in the potential of promise programs, there are broader issues to be addressed in higher education and in the K-12 system. As students transition through elementary, middle, and high school, and finally move on to college, institutions need to work to smooth out transitions between each, she said.

“I truly believe that we need to get students to get some form of satisfactory postsecondary education, so they can succeed in their communities, succeed in the workforce, and succeed with their families, but focusing only on college is not enough,” Gross said. “If we want to make systemic, replicable change, we need to move the train back.”

Staff writer Catherine Morris can be reached at [email protected].