Tylik McMillan, a recent graduate of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, remembers walking miles to vote on his gerrymandered campus, one split between two congressional districts.

“We’ve been seeing tactics like that to make it harder for students to vote in some places,” said McMillan, who is currently the national director of the Youth and College Division of the National Action Network, the civil rights organization founded in 1991 by the Reverend Al Sharpton.

On Saturday, August 28th, tens of thousands of activists are expected to gather in major cities across the nation to protest the latest sweep of voter suppression laws. College students, in particular, will be among those who will gather on that day, which marks the 58th anniversary of the historic 1963 March on Washington where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech."

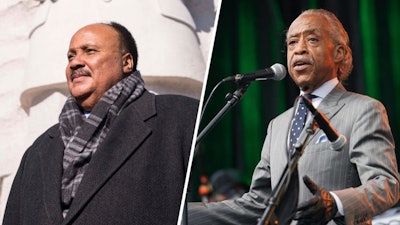

Martin Luther King III and Reverend Al Sharpton

Martin Luther King III and Reverend Al Sharpton

Organized by Sharpton and Martin Luther King III, the son of the slain civil rights leader, March On For Voting Rights comes as Congress debates key voting legislation that also impacts some college campuses.

“For students, the question is whether they can vote on campus or go home to vote,” said Sharpton, the well-known civil rights activist and host of PoliticsNation on MSNBC. “There can be problems if you live on a campus far from home. Voter ID laws are the second problem.”

In states like Texas and Tennessee, for example, student IDs cannot be used when individuals register to vote. Yet a gun license is accepted. “That’s almost unthinkable if it wasn’t real,” said Sharpton in an interview with Diverse.

Dr. Demetri Morgan, an assistant professor of higher education at Loyola University Chicago, researches postsecondary educational institutions and student activism. He has also noticed a disturbing trend that has made voting in some states more difficult for college students.

“We see that because of the transitory nature of many college students and the typical left-leaning demographic of college towns, which is usually more pronounced in the South,” said Morgan. “College students’ migratory shift can shift elections, shift districts, so you see a lot of right state legislators recognizing that. If college voters turn out, they can make big changes where the margins are really slim.”

In an interview with Diverse, King said he believes it is important for students to fight to make changes on key issues that matter to their present, such as the student debt crisis, and future, namely climate change.

“You have to demand what you want,” said King. “These are your rights. You shouldn’t have to demand your rights, but you do have to. We hope that students from around the country will come out on the 28th. It’s not just about marching. We have other engagements.”  Tylik McMillian

Tylik McMillian

There will be sister marches across the country as well as virtual events to help register voters.

“If we want to protect, preserve, and expand our democracy, it is critically important for students to be at the table when those decisions are made,” said King. “My hope is students will continue to be engaged as they were after the tragic death of George Floyd. We saw a consciousness that was awakened for the first time in many years.”

The march organizers are specifically calling on the U.S. Senate to pass the latest voting rights bill named after the late John Lewis, a leading civil rights activist and U.S. Representative from Georgia. Sharpton predicts the bill will make it through the House next week with Democratic votes, but it is unclear what the Senate will decide next.

“That is why on the 28th, we are not going to the Lincoln Memorial. We are going to the Capitol, marching past Black Lives Matter Plaza and past the National Mall with the Capitol building in the background,” said Sharpton. “Because we want people to look at that building and know that there we will decide whether democracy will die in this country or survive.”

McMillan and fellow youth helping with the march or working with people to get out the vote, have been carpooling locals to poll stations, texting voters to vote, and “most importantly, showing up with their bodies,” said McMillan. Because like Sharpton, McMillan said he believes “optics have meaning.”

“We’re not in the business of walking around and getting steps in. We’re in the business of getting structural change done,” he said.

A fellow young activist agrees.

“For too long, we’ve been on the menu but not had a seat at the table,” said Jerome Treadwell on youth voters. Though he is not old enough to cast a ballot yet, the seventeen-year-old has been organizing voters in Minnesota to combat racism in schools.

“The main thing is for youth to figure out how to remain engaged. You can’t just drop the ball and say someone else will handle that,” said King. “I think the last voting cycle showed that when you get the attention of students, they will engage.”

King and Sharpton are also calling for an end to the filibuster, adding that the political procedure’s sordid past is further reason for students to pressure legislators to get rid of it.

“Politicians would use it in the old days to block civil rights and anti-lynching laws, standing up and talking all night long. Yet that is the same filibuster we have today,” said Sharpton. “I watched as students removed on campuses and in public squares the statues of slave masters. But that action is incomplete if we leave the filibuster.”

To Sharpton, that long-accepted procedure is as potent as Confederate memorials to a dark history.

“You cannot just take the statue down from outside in the square but also from inside the legislatures. And that statue goes by the name of filibuster,” said Sharpton, who advises students to email their legislators, get to know who those legislators are, and contact the National Action Network. “We are strong as a collective.”

Sharpton “guardedly hopes” that the fight for voting rights will prevail.

“I always believe that in the end, we will win,” he said. “But I don’t become so optimistic that I won’t be realistic. We will win, but we need to fight every step of the way. Winning is earned. We need to put pressure on elected officials. It is like anything worth having: it is worth fighting for.”

Despite experts cautioning that the voting rights bill may not make it through the Senate, and with continued backlash from the far right, Sharpton thinks back to moments of progress in his life that show him a way forward.

“I have seen too many things win to not have hope,” he said. “In 1994, I saw with my own eyes how Nelson Mandela went from prisoner to president in South Africa. And I saw Obama put his Black hand on the Bible. And I thought about how as a child growing up in Brooklyn, New York I watched Black people on television getting killed. And I lived to see a Black president. I believe and I hope because I have seen struggles win.”

Rebecca Kelliher can be reached at [email protected]